Rania Matar on

Photography, Personal and Collective identity, Unity,

Womanhood, Girlhood, Changing the Narrative, Hope for a better world

and helping Beirut

.jpg)

photo by Dominic Chavez

Time feels like it stands still upon viewing Rania Matar’s graceful and strong photography. Her photographic skills ensure that we are taken into the sitter’s universe, wondering about their thoughts, observing someone’s life captured in an alluring contemporary photographic element, reminiscent of poetic notions, touching images filled with perspectives and empathy and for a moment, while we view Rania Matar’s beautiful and engaging photography, the world feels as though it has gone silent as we hear the powerful messages that her art wants to relay.

Rania Matar's work on identity and quest to find unifying universal elements in women and girls from both Lebanon where she was born and America where she lives, her cross-cultural background that lends itself into the narrative of her work, her prints put forward to help Lebanon rebuild after 4th August 2020, her different series on womanhood and girlhood and dedication to explore issues on personal and collective identity, her project during COVID-19 lockdown, how she started her photographic journey, was all part of our conversation, but we started off by discussing Lebanon and the recent heartbreaking devastation...

Yara, Beirut Lebanon, 2018 from portfolio 'She'

I would usually begin an interview by asking how you started in your field, but in the light of what has unfortunately happened in Lebanon, I want to start by asking you to tell us about the artworks you donated, raising funds for SEAL's Beirut Emergency Appeal and recently to Art Auction for Lebanon.

I felt heartbroken about what happened on the 4th August 2020 in Beirut and needed to react straight away, so I organised an online fundraiser for SEAL, where I sold some of my prints.

I offered 30 small sized prints for $ 1000 each and they all sold within 10 hours. As this was a successful initiative, I created another fundraiser print, and within a week, I was able to raise $ 67 000 for Beirut. 100% of the funds went to SEAL for the Beirut Emergency Appeal.

Usually when devastations happen on this scale, at first it’s all over the news, then they tend to lose exposure. Living in the United States, I know many are preoccupied with the upcoming election and understandably with their lives, so I needed to seize the momentum when we were being exposed to the magnitude of things, and it was incredibly moving for me to see that many Americans contributed to the funds.

For Art Auction for Lebanon, I donated prints of my image 'Nour' from the series 'She'. People can start bidding online from Wednesday, 23 September (10:00 am GMT) to Monday, 28 September (10:00 pm GMT) for this image and other works of art by many artists.

.jpg)

Nour #1, Beirut Lebanon, 2017 from portfolio 'She' - Limited edition prints of this image for Art Auction for Lebanon Funds of all collected revenues go to the following 4 NGOs: @ccclebanon , @AssamehBB, @RebuildBeirut and @Bebwshebbek and to the artists https://www.artauctionforlebanon.com/

Ghinwa, Khiyam Detention Center, Khiyam Lebanon, 2019 from portfolio 'She' - Limited edition prints of this image were donated with 100% of the raised funds going for SEAL Beirut Emergency Appeal

You have taught photography in Lebanon, how was that experience?

In my early work in Lebanon, I photographed a great deal in the Palestinian refugee camps. Teaching photography there, was a way for me to give back, though I did not teach as much as I would have liked to, but over the years, I have always included many of the women, girls and their families from the refugee camps into my work. We forged a relationship, one of the girls I have photographed since she was 4, and she’s now 21.

You studied architecture in Beirut. How did you then transition from architecture to photography and how much does architecture impact your work, if it does at all?

I started studying architecture at AUB (American University of Beirut), then in 1983 the situation in Lebanon became very bad, so in 1984 I left and transferred to Cornell University in upstate New York.

I had already fused my love for art with architecture by practicing painting and drawing. Furthermore my university thesis was about designing in museums. So the artistic element was a part of my visual training. Then when I was pregnant with my fourth child, I decided to take some photography workshops as I wanted to photograph my children. Little did I know, that I would fall in love with the medium. It went beyond taking pictures of my own children, I enjoyed telling stories through the tool of photography. For a while I was doing photography on the side, raising four children and still working as an architect.

After 09/11, most of the news coming out of the “Middle East” was so divisive, it was set up with the notion of a “them versus us”. For the first time, I started to question my whole sense of identity, and I wanted to tell a different story about the “Middle East”.

So I started going back to Lebanon, taking pictures, and before I knew it, I become a photographer and I wasn’t doing architecture anymore.

After finding photography, you had many exhibitions, nominations, you became a Guggenheim fellow, how did all these milestones make you feel and how do you view your role?

There have been many milestones, but I feel like it’s a journey. The bar keeps changing, but as a person, at my core, I haven’t changed who I am.

Each step has made me feel overwhelmed with joy and much gratefulness.

Feelings are interesting, for an artist I think many things are felt like a validation, that on some level the work we do matters and has touched people. I hope that I keep making work that keeps inspiring me and inspiring others.

I want to be true to my work. It’s always important to remember why I am doing what I am doing. Art means something to me; and I think that essence resonates with people. I feel it’s good to reflect, that when one becomes on some level a part of the art world, not to lose the integrity of what one is doing.

You have previously mentioned that you wished to show through photography, the universality of womanhood and adolescence, that there is no "other"; can you share with us how the notion of a collective identity first established itself in your work and the messages you want to convey.

I have a foot in both the United States and Lebanon, conveying that notion started as a personal journey. I’m originally Palestinian, born and raised in Lebanon, on one side, I have that sense of my identity, but I am also American, where I live and where my children were born, so it’s very much about tying those two cultures.

The news still feels very divisive, and the more I work with women and girls in both those cultures, the more I realise that there is a shared humanity, a universal bond, like aspects of growing up, going through puberty or becoming an adult.

The spaces the sitters inhabit may differ, for instance, one person is living in a refugee camp, another in up-scale Lebanon, but even when lives are different, there are these transitions in our personal life that are very universal.

Every girl or woman I photograph is an individual, but I want to focus on that sense of the collective identity of going through the stages of life. I feel and hope that the work does that. Some images don't give themselves up to whether they were shot in Lebanon or in the United States. I think that is important, because people tend to have a very specific image in their mind of what the “Middle East” looks like.

Andrea, Beirut Lebanon, 2010 from portfolio 'A Girl and Her Room'

Danielle, Jamaica Plain Massachusetts, 2010 from portfolio 'A Girl and Her Room'

Rocio, Dorchester Massachusetts, 2010 from portfolio 'A Girl and Her Room'

Reem and Rania, Bethlehem West Bank, 2009 from portfolio 'A Girl and Her Room'

You mentioned that at one point you were questioning your identity, your work has reacted against the lens of orientalism

There used to be a lot of art about the “Middle East” which catered to a specific audience that may have had preconceived ideas about the region. I resist that so much, I’m tiered of seeing a singular orientalised narrative.

Some seem to attach only the thought of war to the region; it is so much more than that. I hope I am resisting this through my work. Sometimes people want to impose a particular narrative on things or places. When I photograph people I aim to capture their narrative. When I photograph women wearing the veil, it's because it is a part of the texture of the “Middle East” and part of the identity of the women who are wearing it.

I photograph much in the region, and all its pluralities, because that’s important to me, as this is who I am - for instance now, I feel very anxious that I am not in Beirut with all that's happening there.

You have managed to turn orientalism on its head;

In your series ‘Ordinary Lives’ you photographed nuns who are veiled and women who are veiled, with no differential element for the viewer to recognise to which community the women belong to.

I had a show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in the U.S in 2009 and the curator mixed those two sets of images to push back on the prejudices that some would make, where for some, one set is acceptable and the other one not and vice versa.

.jpg)

Newspapers, Beirut 2007 from portfolio 'Ordinary Lives'

Three Nuns, Beirut 2008 from portfolio 'Ordinary Lives'

Fully Covered by the Sea, Beirut 2005 from portfolio 'Ordinary Lives'

Coffee on the Terrace, Convent of Saydat Al Nouriyeh, Chekka Lebanon 2008 from portfolio 'Ordinary Lives'

A few years ago I was part of the exhibition “She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World”. One of my images that the curator picked, is also the cover for my second book ‘A Girl in Her Room’. It depicts Christilla in her pink bedroom with a Marilyn Monroe poster behind her. When it was displayed at the exhibition, the curator was asked many times to confirm that the image was from the "Arab world", because to those that were asking, they did not reference that imagery I had portrayed with "Arab women". The image throws people off, and it’s important for me to be shedding that stereotype a little bit.

Christilla, Rabieh Lebanon, 2010 from portfolio 'A Girl and Her Room'

You take us into the sitter’s universe through your photography. Do you set-up the photoshoots or do they happen naturally, and how does your relationship develop with the sitter throughout the shoot, do you have to get to know the girls and the women or do you prefer some distance between you?

Every project is different, but I don’t set things up.

In my early black and white documentary images, I would sort of disappear more into the background and observe the moment. I still work in the same way, I don’t use a tripod or any lighting, I walk around and I work intimately with people. That has stayed consistent from the beginning until now.

In my newer work, I still don’t set anything up, I feel though, that the process becomes a collaborative experience between myself and the women or girls. It develops somehow organically throughout the photoshoot, we start the process and then as I shoot, i’m starting to get to know the sitter better, they are getting more comfortable, and I’m giving them room to express themselves.

Have you ever been interested in photographing men or boys?

I have been interested in doing so. I have twins, a boy and a girl; whereas my daughter accepted that she inspired my work, my son was adamantly against the idea. But I ignored that, and photographed a couple of boys during the project ‘a Girl in Her Room’. I realised though, that it was a very different relationship that was being created, as it was also very much about my own identity.

I am seeking to understand through the medium of photography, womanhood and girlhood across the ages which I have personally experienced. I lost my mother when I was very young, i’m learning that relationship of being a mother through my own children, and there’s a whole exploration of being a mum that I still want to delve into with my work.

There are projects which include men and boys. In the series ‘Portraits and Identity’, ‘Invisible Children’ where I photographed Syrian refugees and the series ‘Across Windows’ that I shot during lockdown, which was about distance.

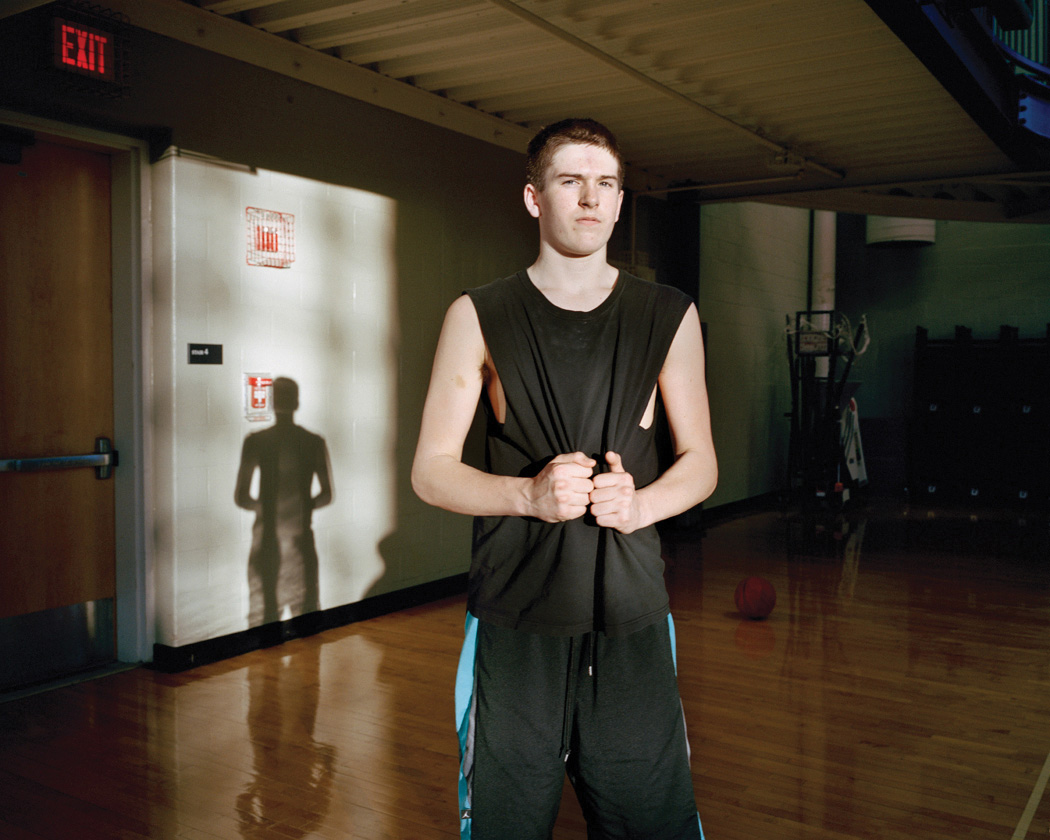

Max 15, Dedham Massachusetts, 2014 from portfolio ‘Portraits and Identity’

Hassan 15, Beirut 2014 from portfolio 'Invisible Children'

Little Brothers, Beirut 2014 from portfolio 'Invisible Children'

Lockdown propelled your new work ‘Across Windows', did that happen straight away where you wanted to pick up your camera or was it more of a gradual process? How did you find lockdown?

The first couple of weeks nobody knew what was happening. I usually have a busy schedule, but the period of lockdown forced me to slow down, and though it was during a difficult time, slowing down felt good, and I appreciated having my children at home again.

What was very humbling during that time, was the response towards the fundraiser for the Beirut Emergency Appeal. It was incredible to witness so much care and generosity, it showcased how much humanity can really come together. It’s something that I’m taking away with me from that period of time.

I was also working towards a book on my series ‘She’. When all the images were laid down on my floor, I realised many of them had both a sense of the inside and outside. I posted some of them on Instagram, because that’s what I was going through then, and inevitably I started to be within that frame of mind.

Then one day, while I was by my kitchen sink, across the yard I saw my neighbour, a woman in her kitchen. I instinctively thought, there’s something interesting between that relationship, that this is how we are going to be viewing each other from now on.

When on another occasion, I saw her sitting on her window seat reading, something clicked in my mind that this perspective of seeing each other would be interesting to explore in a project. I then did a call out on Instagram for anyone to reach out to me if they wanted to be photographed. I was pleasantly surprised by the amount of people that did, making me take notice that time was now more accessible to us all, and we were all creating connections with each other in ways we can.

.jpg)

Cyrus, Brookline, Massachusetts 2020 from portfolio 'Across Windows'

Austin, Boston, Massachusetts 2020 from portfolio 'Across Windows'

.jpg)

Nadav, Brookline, Massachusetts 2020 from portfolio 'Across Windows'

Jayne, Boston, Massachusetts 2020 from portfolio 'Across Windows'

Do you reach most of your sitters through a public call or are they people you know?

I’ve never made a public call before. For most of my projects, I either stop people on the streets, but don’t partake in a photoshoot there and then, I send a description of the project and most agree, or I’ve been introduced to the sitter.

For the ‘Across Windows’ series, there was no other way of reaching people during lockdown than an online public call, it was an interesting use of how social media can work. The Boston Globe also made an article about the project, which further resulted in people reaching out to me.

How do you feel about social media as a tool and how much has it impacted you?

I have a love hate relationship with social media, I never know how much is too much to share. It’s a fine line I am navigating between sharing pictures online and waiting to show them at an exhibition. There is a sense that instead of us engaging with an image, we are scrolling through them and then all of a sudden not even properly looking or absorbing the art, there’s something kind of sad about that. The good thing about social media, is its capacity to reach a large number of people, share work across the world at fast speed and to connect with others.

However there is the danger of how it may affect us, when we post a picture if we don’t receive likes for an image that we like, then that may start to make us question ourselves.

My daughters are in their 20’s and I see how much pressure social media can create. People’s lives look perfect even though that may be far from true. The series ‘She’ started I think as a reaction to that, a project filled with textures, our sense of tactility, our physicality with nature and instinctive emotions. It’s about woman owning the landscape, and I want this to be about empowering.

Hellen, Snowmass Colorado, 2016 from portfolio 'She'

Alae, Khiyam Lebanon, 2019 from portfolio 'She'

.jpg)

Sara and Samira, Bourj El Barajneh Refugee Camp, Beirut Lebanon, 2018 from portfolio 'She'

Ciearra, Winston-Salem North Carolina, 2018 from portfolio 'She'

Mariam, Khiyam Lebanon, 2019 from portfolio 'She'

Your work is raw and organic, whether its the girls you photographed in ‘She’ or in ‘A Girl and Her Room’, equally in ‘Unspoken Conversations - Mothers & Daughters’, seeing between the mothers and daughters the silent moments that say so much.

I started 'Unspoken Conversations' when my daughter was leaving for college, it was a very personal project. Once again examining my relationship with my daughter and reflecting on the loss of my own mother.

Betsy and Melinda #2, Dedham Massachusetts, 2016 from portfolio ‘Unspoken Conversations - Mothers & Daughters’

Your photograph of Leila and Souraya from that series is strong, they are in front of a painting which visually presents two different ways a woman can project herself.

When I arrived to do the shooting, there were many paintings in the house. After I inquired about them, I discovered, that the mother is a painter. The particular painting in the image I shot, according to the mother, represents her daughter in two figures, conveying two sets of feelings that could be sensed during teenage years, on the one hand wanting the world to see you and on the other, and at the same time, wanting the opposite. Once I found out that the painted portraits were of her daughter, it felt fitting to have it included in the photograph.

What would you want to say to the next generation?

To the young generation in general, I want to say how inspiring and brave they are. They are not waiting for things to happen, they are leading the way.

I attended some of the protests in Lebanon last fall (2019), where I took some photographs (not yet up on my website). It was incredible to witness the atmosphere, where the youth present were united for a better Lebanon for all, they didn't see religion, they didn't see differences, or any aspect that had once divided people. I believe, without wanting to sound cliché, that they are going to change the world.

The same thoughts I feel towards the youth in the United States. They have been protesting for Black Lives Matter and standing up for rights.

I am hoping that the next generation will have room to make things better.

Injured Bird, Brookline 2004 from portfolio Family Moments

Rania Matar was born and raised in Lebanon and moved to the U.S. in 1984. Matar's work has been widely published and exhibited in museums worldwide, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Carnegie Museum of Art, National Museum of Women in the Arts, and more. A mid-career retrospective of her work was recently on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, in a solo exhibition: In Her Image: Photographs by Rania Matar.

She has received several grants and awards including a 2018 Guggenheim Fellowship, 2017 Mellon Foundation artist-in-residency grant at the Gund Gallery at Kenyon College, 2011 Legacy Award at the Griffin Museum of Photography, 2011 and 2007 Massachusetts Cultural Council artist fellowships. In 2008 she was a finalist for the Foster Award at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, with an accompanying solo exhibition.

Her work is in the permanent collections of several museums, institutions and private collections worldwide.

She has published three books:

L'Enfant-Femme, 2016, with an introduction by Her Majesty Queen Noor, and essays by Lois Lowry and Kristen Gresh. Selected best photo book of 2016 by PDN Magazine and Foto Infinitum, and Staff Pick by the Christian Science Monitor.

A Girl and Her Room, 2012, essays by Anne Tucker and Susan Minot. Selected best photo book of 2012 by PDN, Photo-Eye, British Journal of Photography, Feature Shoot and L'Oeil de la Photographie.

Ordinary Lives, 2009, essay by Anthony Shadid. Selected a best photo book of 2009 by Photo-Eye.

She is currently associate professor of photography at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and regularly offers workshops, talks, class visits and lectures at museums, galleries, schools and colleges in the US and abroad.

Brigitte and Huguette, Ghazir Lebanon, 2014 from portfolio 'Unspoken Conversations - Mothers & Daughters’