Ali Cherri on Art exploring The Politics of Visibility,

Hidden Histories, Objects, Value, the Gaze,

and Cycles of Destruction, Creation and Healing

Ali Cherri’s work expands our thoughts, guiding perceptions and propelling a variety of ideas.

Divulging into life, death, war, nature, destruction, hidden histories, the politics of visibility, power, trauma, healing, value, representation, the gaze, and materiality, Ali Cherri’s art unravels to reveal those notions with layer upon layer of depth of knowledge, research, exploration and lived experiences.

His work releases an array of perspectives, carrying within it important questions, attentive to the objective of representation, to rendering the hidden visible, bringing the shadows into the light, uncovering power relations, and directing our gaze into looking at and through different angles.

Works such as ‘Un Cercle Autour du Soleil’ and ‘The Disquiet’ carry a cluster of questions that pierce into examining the Lebanon in relation to destruction by way of both war and natural disasters. ‘Somniculus’ approaches the relationship between living and dead bodies, the concept of nature and culture cultivates ‘The Gatekeepers’, and a set of watercolours called ‘Dead Inside’ bridges some of these concepts.

Seeking to decipher the essence of value, as well as delving into the notion of the gaze, concerns much of Ali Cherri's work, including in ‘Fragments’ and in the artist’s exhibition ‘If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?’ at The National Gallery, which through the lens of the wound looks at responding to vandalised paintings. The title borrowed from Shakespeare’s play 'The Merchant of Venice', is used as reference to the artist personifying the artworks in regards to their need to be amended or heal from any done damage. And bringing his artistry to the the 59th Venice Biennale, Cherri’s film ‘Of Men and Gods and Mud’ showcases mud’s dual aspect of creation and destruction and his sculptural figures 'Titans' represent ancient deities. Ali Cherri has been awarded the Silver Lion for a Promising Young Participant in the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia: The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani.

Ali Cherri’s art is thought-provoking, making us look twice at an object and at moments in time. As our conversation covered his projects and the Lebanon, our discussion began with what incited him into a world of art…

What first evoked your interest in art and drew you in?

I like to think that it happened by accident. I didn’t plan my path. At the end of the Civil War I grew closer to the generation of post-war artists in Beirut. Though I was younger than them, my first experience with art was looking at their work, going to their exhibitions and eventually working with them, from designing books, to stage set design as well as being in a theatre play. Slowly and very organically I got drawn into art, all whilst studying design at AUB and later doing a Master’s degree at DasArts in Performing Arts.

Your work is linked to Lebanon, and much of it stems out of living through the country’s Civil War. There’s a direct relationship between your art and looking into violence, wounds, the uncertainty, trauma, but also healing; can you share with us a bit about growing up in a fractured city, and about some of your work such as ‘Un Cercle autour du Soleil’ and ‘The Disquiet’ that explore those notions.

Living and growing up during the Civil War in Lebanon as well as throughout the post-war reconstruction, was a very marking experience. It shaped who I am. At the same time, that just happened to be the circumstances I grew up in. That’s what I knew. Beirut for a long time was the only city I was familiar with; and I lived it.

And as that was the only experience I had, violence and questions relating to trauma and to war were obvious themes that concerned and enraptured me.

Some of my earliest work related directly to Beirut, questions on living in an unsettled reality or an unsettled land, came through.

‘Un Cercle autour du Soleil’ filmed in Beirut and created in Amsterdam as I was pursuing my masters degree, was my first short film. It was also the first time in my life I had left Beirut, the first time I received some distance from it.

The separation allowed me to reflect back on my experiences. The short film explores man made violence, the parallels ruins of the city have with the ruins of a body, points on violence, sleep, the gaze and the return of the gaze, questions regarding death, our relation to it, the subject of survival, and what that means. The film still holds all the core attributes of which I am still concerned with today.

Stills from 'Un Cerlce autour du Soleil'

Video, DV, Color, 15min, Stereo, English DasArts - Amsterdam, 2005 — Digital Arts Award

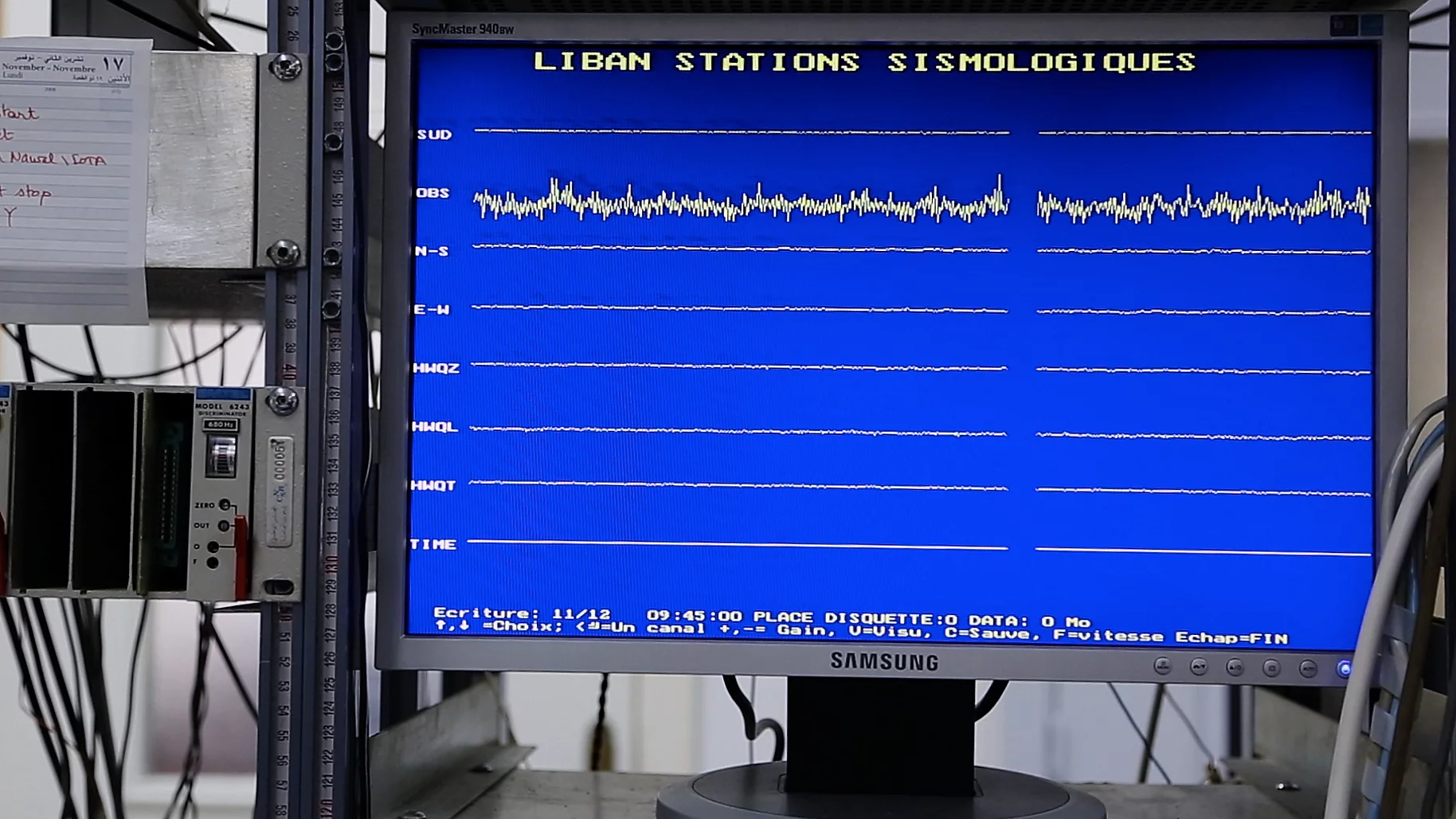

‘The Disquiet’ looks at violence from another perspective, it speaks of nature’s role, delving below the surface, where devastations may come from a natural disaster; the earth shattering at the hands of nature.

Lebanon sits on three fault lines, two of them are very active. I was interested in a disaster’s cyclical times. We know that whenever an earthquake occurs, another will follow. It could be in 50, 100 or a 1000 years, that’s to be seen, but for sure another will emerge.

Looking through the prism of science, how it may quantify destruction, and studying seismic activity, formed part of my project. I reviewed seismographs, computers that register the seismic movements and tensions that lie beneath the earth, always alongside having the body and its place in mind.

It is said that Beirut throughout its history, has endured seven times a large scale natural disaster. Currently in Lebanon there are about 60 earth tremors a day, and I feel every one of them. Examining the body as a seismograph, one that registers tremors as a devastation is happening, charged ’The Disquiet’. Hence, the film was in parallel a way to think about being born and raised in Lebanon with these cycles of violence and moments of destruction that keep on coming back.

Both man made violence and nature’s rage have moulded the Lebanon.

The myth which resides within Lebanon's narrative, one of resilience, of being born from the ashes with the phoenix rising, are all urban myths we grew up with. Sadly, destructions are also part of our reality today. The 4th of August 2020 explosion at the port of Beirut was colossal and devastating. A circle can be drawn around a moment of collapse, but the moment itself remains outside of representation. A catastrophic situation is often assessed before or after, yet for the actual moment, words fail to describe it and images never do justice to it; neither can give a full account. In the aftermath of the Beirut explosion, many relayed what they were doing right before it happened, and what ensued straight after, concerning their loved ones, their loss, injuries, all these traumatic stages, but the actual moment it happened, was beyond description.

So the questions I search for are, can we represent the actual moment a devastation occurs, can we also tell the story of trauma, can trauma have a face or have a shape, and can it be quantified, these are the main focal points that have been and are still central to my work.

Stills from 'The Disquiet'

Stills from Film. HD, Color, 20min, Stereo, French/English - 2013

Accessing Lebanon from different view points, both war and nature's traumatic aspects form part of each other in a very small country. Was it from those earlier films that you started to decipher and look into what you have called the politics of visibility?

The question of representation has always been very central to my work, and with that, the very idea of whether devastations can be depicted.

Experiencing trauma from either nature such as an earthquake, or man made violence such as war, and thinking of them as the same essence, without stating that these catastrophes always generate the same reactions, but rather taking into consideration, that they may come from a same certain place, we can then see how, above the surface and below the surface, violence is there.

Thinking about these works on Lebanon, to that of you exploring hidden histories in museums, both entities may relate to each other. Lebanon barely has a consensus on its history, it is a hub for histories—some of them hidden histories.

You were born during the Civil War, growing up in a divided Beirut, half of it was hidden to you. To have half of your city hidden, that, along with the violence, is also part of the trauma and part of the actual violence.

Exactly, and that is central to ‘Un Cercle Autour du Soleil’, where it delves into growing up in a city which was unknown to me. I made an alliance with the night and with darkness. As is relayed in the film, in darkness I could give shape to my ideas, I could live in whichever world I wanted, I could invent the city. Alongside this persistent idea I have of living in a constant ruin, a city that eats itself.

As a child I knew only half of Beirut, many places I couldn’t go to, even if it was accessible, it was dangerous.

The post-war reconstruction consumed the work of post-war artists. Questions such as, which type of city do we want to live in and what shape should it take, were asked as part of their work, on account of what was happening then, which was a push for a certain imagined Beirut. Beirut was seen as an agent city of the future, but that meant Beirut didn’t have a present, it only had a past projecting into the future. It left nothing to reflect back on the years of war. That was a very neoliberal project, building a city for the future that was not necessarily for the residents of Beirut, but one to attract tourists from Europe and the Gulf, and to bring in investments. I am not proclaiming that it should have remained in ruin, but many of us felt then, that the city didn’t belong to us, we felt alienated. It comes back to the question of representation, of who owns what. The narrative of the city we live in, does it belong to the residents to structure the one they want, or is it just investors who come in with big money and think of it as a cartography and abstract ideas? It’s part of the mythology of the nation, and my short film was also looking back at that time.

This initiated you to pursue hidden histories and stories in museums?

We are sitting and talking together in The National Gallery museum, by calling it The National Gallery, it is therefore also building an image for a nation through beautiful artworks.

My work around institutions stem from these same ideas, who gets to tell the story, who gets to write the narrative, and how do we construct a national narrative around broken objects. Looking at the museum as a power structure, that produces narratives, ideas and myths around objects.

I am interested in that mechanism that generates stories. Seeking by what means are objects housed in a museum given a voice; do we speak of them, of a past, of a construct? I look at objects and think, how far can a constructed narrative still hold? What are the limits until it collapses? So my work explores that, propelling to the surface histories in relation to what has remained hidden and what has been brought out through a dominant narrative. I pursue including more complexities within the space of a museum.

Hidden histories are also found in tools we carry, through technology and the structure of algorithms and the power dynamics that entails.

Everyone has a history and a voice, the question is which voices are allowed to be heard, and which have impact; which histories are part of the dominant one, and who has been left marginalised or left invisible.

At The National Gallery after a year’s residency, you are presenting, 'If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?’

The exhibition showcases your responses to your research on five paintings that in some way had been vandalised whilst on display at The National Gallery.

Those five paintings, apart from them having been attacked, what were the other reasons you chose them for? Were there many other paintings that you found in your research had been vandalised? And how has been your experience throughout your residency?

My time in residency at The National Gallery has been truly amazing. It’s an event in my personal and professional life that has brought me so many positive aspects. The institution made me feel extremely welcomed and a part of the team. The whole experience is something I very much cherished and appreciated.

The choice of the five paintings that fuelled the work for 'If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?’ was quite intuitive. Some of the vandalised artworks touched me more than others, either because they were spectacular, or because I was connecting and feeling with a painting; those were my guidelines.

The idea behind the project is wanting to respond to those broken bodies that are the paintings.

I am very interested in creating a community of broken bodies, a sort of solidarity between them, where everyone can help each other and share experiences.

As I say this, I am referring to human and non human bodies. I treat all broken bodies almost the same.

Many paintings in museums are vandalised, it’s not usually something museums like to talk about, but it is happening all the time everywhere.

The question of looking at a museum as a political site of protest, and looking at wound culture, how a museum deals with those wounds or violence that have been inflicted on artworks, comes through the exhibition, and it relates back to the politics of visibility that my research and work is plunged into.

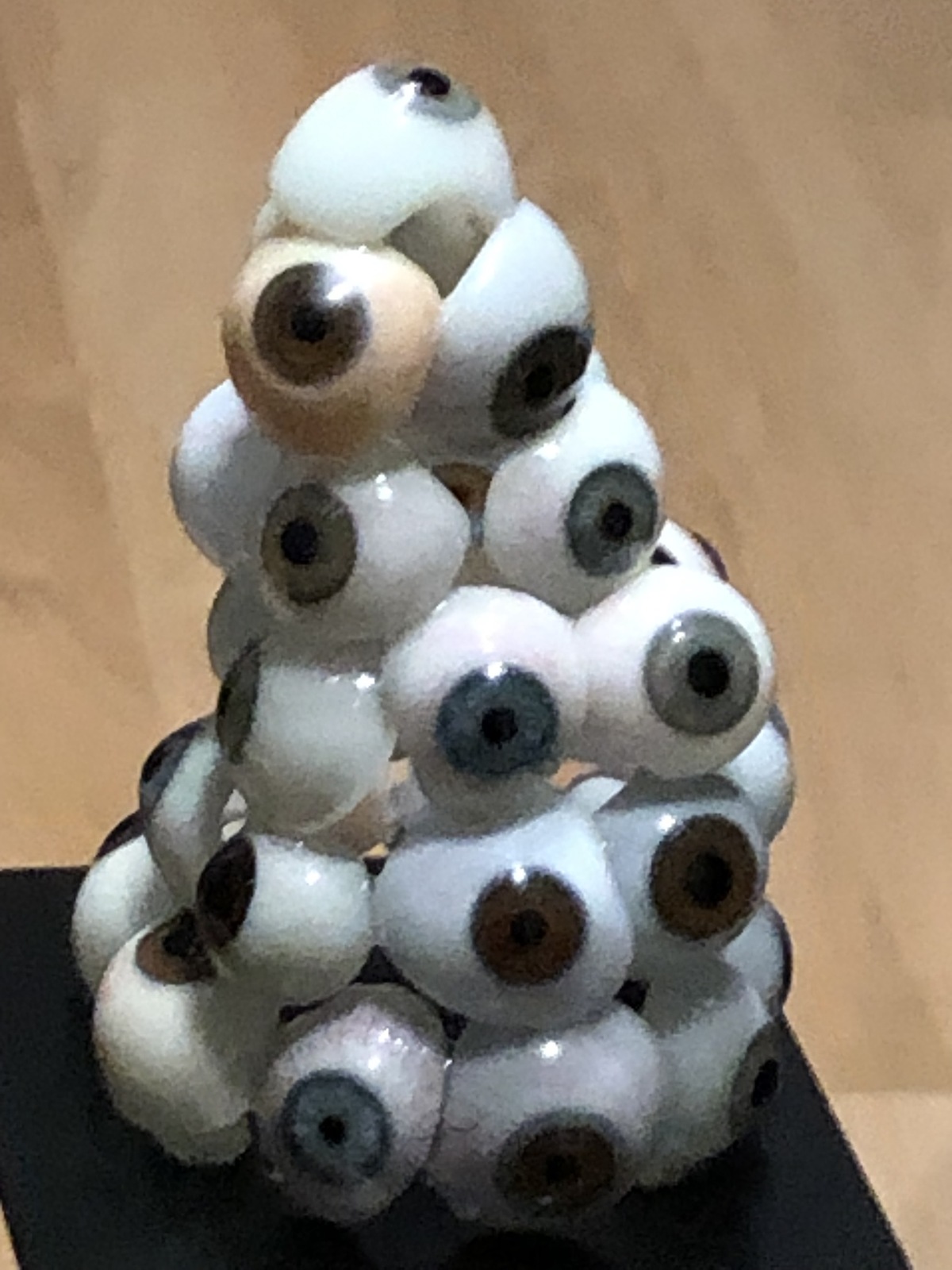

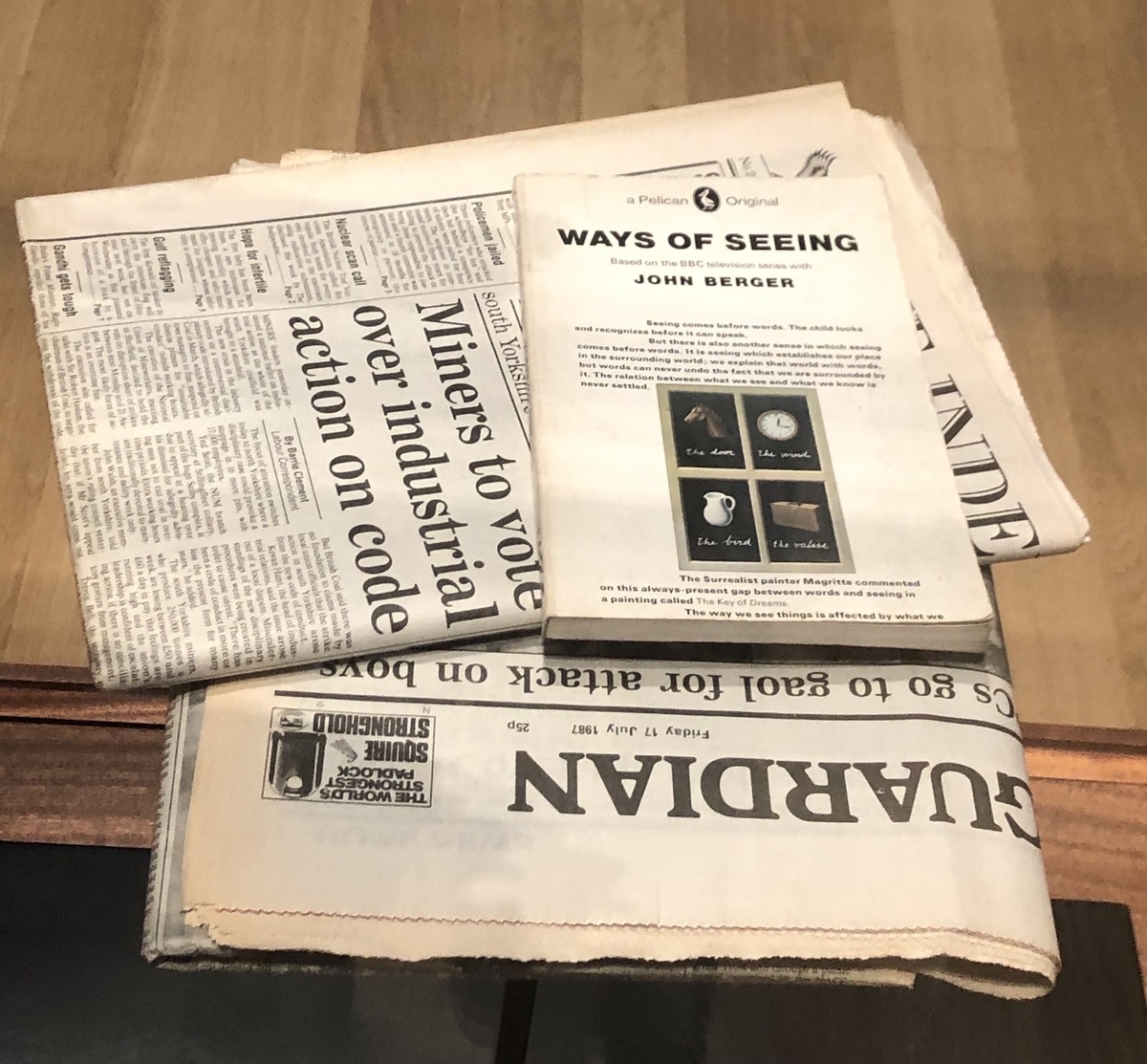

Your work for this exhibition is presented in cabinets of curiosities. In one of them you have placed John Berger’s book ‘Ways of Seeing’, which is a nod to your thoughts on the gaze, the act of questioning what is real, and what is or is not hidden.

It is placed in the cabinet that responds to Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘The Burlington House Cartoon’ which was shot at in 1987. I took the impact of the bullet on the drawing and enlarged it about 600 times up to the point where it can become the central object within the cabinet; as a wound taken to an iconic size. It even feels like it’s emulating a looking eye.

Next to it in the cabinet, is a small sculpture from the 19th century made of prosthetic glass eyes. I was interested in how this object can make us think about the study of the gaze and what that entails. These glass eyes emulate an eye, but fail in their function.

The glass eye sculpture makes us reflect on the notions of visibility, who sees, who is seen, who pretends to see and what is failed to be seen.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist ('The Burlington House Cartoon') after Leonardo, 2022 . Cardboard, glass eyes, newspapers, (The Independent, The Times, and The Guardian from 17 July 1987 (the day of the incident on the painting) and a book (John Berger, Ways of Seeing). Commissioned by The National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme

Those glass eyes are the same type of eyes that are used in taxidermy, where they emit a feeling that we are being looked at, the impression of being scrutinised. The capacity of taxidermy eyes to make us the viewer feel like the subject, feel the vulnerability that they are looking back at us, returning our gaze; a mutual moment.

John Berger’s ‘Ways of Seeing’ is like an artist’s bible, most have at some point either read or been acquainted with it.

One aspect which I had forgotten about upon starting my residency and research, was the fact that the tv series of ‘Ways of Seeing’ in the very first episode, starts off with John Berger cutting a painting at The National Gallery. The tearing sound charges the knife cutting through the canvas.

That’s a wonderful serendipitous connection, like fate leading to all of this

Things sometimes fall into place for certain reasons.

There are several connections, even with gestures. In my previous work ‘Somniculus’, I cut off bandages that cover my eyes, trying to regain sight.

I think we have lost our sight to a consumerist society, to neoliberal capitalist societies, where our desires are constructed by commercials and by what we see, aspects that are artificially produced.

And it’s exhausting, branding infused into everything

It’s exhausting, and I think we have lost the battle of the gaze, I cannot compete with television, with advertisement, with whatever is online. Trying to win over our gaze onto other means and other perspectives is constant.

Self Portrait at the Age of 63, after Rembrandt, 2022. Wax and metal frame, wax head created by Andrew Lacey. "Suspended in the centre of the cabinet hangs a shrunken rendition of Rembrandt's head from his self portrait. The painting was vandalised with paint in 1998" - The National Gallery. Commissioned by The National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme

All the objects placed in the cabinet of curiosities at The National Gallery deal with the notion of value, and what we value as a society

In our society certain objects are given more value than others. We produce knowledge and value through taxonomies; so part of my work is to introduce within a museum what I call infiltrators.

Objects in auction houses that have been demoted in their value, and not considered of worth to be placed in the museum system or high end galleries, or even high end auction houses, are sold for very little. Sometimes I buy a whole case of varied objects which have been placed together for no other reason than they were thought to be of no value. From there, I bring those objects into the fold of my work, accompanying them into the museum and treating them as if they already had the same status as the objects chosen by an institution.

The cabinet of curiosities provides status and thus enables us to see how value and our desire over things are constructed.

I have previously displayed objects on a light table such as with my project ‘Fragments’ which is made up of archeological artefacts. I consider what these objects lose when they enter the museum, they come without their shadows. Therefore, these light tables raise the shadows of the artefacts, to become suspended objects.

In both projects, there is no mention of the objects' provenance, and I try to treat all of them equally, even the fake ones. A thousand year old object, could be placed next to a fake 20th century piece. It’s about looking at materiality, giving value to each object and not to discourses.

'Fragments'

Installation, Archeological Artefacts - Light Table - Variable dimensions - 2016

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus'), after Velázquez, 2022. 19th Century Marble Head, wood, glass eye and velvet . "This sculpture references the reclined figure of the Goddess Venus of Velázquez's painting which was cut multiple times by a suffragette in 1914." "Two carvings joined from different materials and eras - a 19th Century marble head with a Palaeolithic styled ritually scared body of an objectified female deity, often referred to as a 'Venus'." - The National Gallery. Commissioned by The National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme

Just the fact that an object is placed into a museum, value attaches itself to it. It’s interesting to think about the power an institution has in providing that. It leads us to question, do other objects not speak to us or do we not listen to them? And that takes us back to exploring the power of the gaze. Both these notions that also came together in ‘Somniculus’.

I shot ‘Somniculus’ across different museums in Paris. Sleeping in empty museums was quite eerie but also felt familiar.

Somniculus means light sleep in latin. In light sleep, we are in an elevated state, our eyes are closed, but all our other senses are awake; we may still hear sounds, smell and feel if someone is approaching us. It’s just the gaze or the sight that is lost in terms of senses.

In ‘Somniculus’ I propose a way to encounter other bodies within the museum, by having a body present amongst dead objects/bodies. A relationship between the living and dead is created, breaking the hierarchy that humans are a higher species, and making us think about the relationship between nature and culture and how we relate to the environment around us.

'Somniculus' . Still photo ; Video Installation 2017. Video HD, color, sound. 14'40''.Coproduction :Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux.With the support of: Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature - Musée du Louvre • Muséum national d’histoire naturelle - Musée de l'Homme - Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac

You’ve referenced the Guerrilla Girls with the question “Do animals have to be dead to enter the museum?” This reference of yours came to mind when I was thinking about ‘Somniculus’ in tandem with ‘The Gatekeepers’ at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille. I thought of Edward Said, his work about ‘Othering’ in his book Orientalism, and I started to look at part of your work through that lens, and wondered if it had to do with a struggle of being accepted, being seen as ‘Other’, as if asking does this ‘body’ have to be dead to be accepted

That’s an interesting reading. To a certain extent, it does have to do with systems of dominance reducing systems of knowledge; and that system of western production also functions on the categories of nature and culture.

In Marseille, the work was a comment on that complete separation between the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle (Natural History Museum) and the Musée des Beaux-Arts (Museum of Fine Arts) where both sit in the same building face to face, yet have never collaborated with each other.

Whilst working on ‘The Gatekeepers’ the institutions told me it was the first time they came together on a project. That was a sign that a distinction was being subjected to the entities of nature and of culture. But i wanted to pay homage to all the dead animals who are in the museum, and bridge it as a natural part of culture.

I look at whichever systems of dominance there are. The totem poles in ‘The Gatekeepers' use a vertical way of telling history, they are like sites of producing stories, and are also icons to differ danger. They hold multiple functions, and I view them as alternative proposals to certain dominant narratives.

'The Gatekeepers'. Manifesta 13 - Marseille 2020; Palais Longchamps - Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille . Wooden poles, metal, taxidermy,woodcarving,various objects.Commissioned by Manifesta 13 Marseille.Supported by Ammodo, Drosos Foundation & N.A!

In respect to ‘Somniculus’, Tarek El-Ariss wrote in his text that he perceived it as the refugee, a figure that sneaks into a museum to sleep, as someone might do on a park bench, in a public arena. It’s about contemplating the museum as a space where that could happen, hosting bodies that have lost their home.

'Somniculus' .

Still photo ; Video Installation 2017. Video HD, color, sound. 14'40''. Coproduction :Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux. With the support of: Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature-Musée du Louvre•Muséum national d’histoire naturelle-Musée de l'Homme-Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac

And it did happen, in the shape of bodies sleeping in museums for protection. In Aleppo we heard about people protecting ancient artefacts, and recently in Ukraine, news has come out of civilians finding shelter in the institution that is an art school.

Yes sadly, the museum as a refuge has happened many times in history.

Bodies that have fallen out of the system, whether they are refugees or not, or whether they are living with difficulties, they belong, but are seen as symbols of not belonging.

You use your own body in your work.

Through the years of war in Lebanon and the aftermath, sentiments may go through it first and foremost,

When I use my body it’s not about my own personal self, it’s about a body. I use it out of practicality and accessibility, it’s the easiest one to convince to be in the work and to film.

And out of as you mention, my experience of the war has gone through the body that I have, that’s how I feel everything around me. I therefore take that as ground zero of my knowledge, where everything starts; and through this personal body, I try to talk about collective bodies.

It’s never solely about my own personal experience, even when I say " I " in my work, I am associating the " I " to other people’s stories.

For instance in ‘Un Cercle Autour du Soleil’, when referencing growing up in Beirut, I related with Yukio Mishima’s ‘Sun and Steel’ as he discusses growing up in Japan during the Second World War. His account is a completely different one to mine, and his experience is a far and distant body, but at the same time, I felt we shared the trauma and the effects of violence on our bodies.

Has the notion of belonging, the concept of identity, also played its part?

If you mean national identity, I find that a hard question for me. Belonging and the construction of an identity, whether belonging to a state, a nation, or to a collective past, is problematic in our narrative. Growing up in a dysfunctional construction of a national identity and of a self, made it in a way, overbearing for me to go into. It’s still problematic and honestly it’s not something that I miss looking through.

We are currently seeing a come back of nationalism rising in the world and once again it’s a cycle, a troubling cycle.

There’s a backlash to globalisation.

And yet, we seem to be now entering a whole era of the Metaverse, which is bound to affect in terms of what we see, what is real, what we learn

It is fascinating what is happening with the Metaverse or even NFT’s, but it’s not something I can feel. I’m more of an observer in that field.

There are different layers of what we see and feel and what affects. If viewing one of the cabinet of curiosities at The National Gallery, even without text or knowing the context of the work, they are still relatable, because the reflection of violence is something many of us have experienced, whether indirectly through the news, films, technology and so forth, or directly. That entity, can speak to us on other levels beyond the knowledge of art.

Other subjects have fuelled your interest such as archeology

I am interested in the gesture of archeology, the digging, the objects, as well as everything that comes with that, but what I really feel for, is how we care for broken things.

Because we are all a little bit broken

Yeah i think we are.

Can that be fixed? In regards to you exploring healing in your work, taxidermy preserves, is your interest in that, a way to preserve something that is broken?

What fascinates me with taxidermy is the immortalisation of death and not of life. In other words, It makes the animal dead forever and that moment of death last a lot longer than it should have. We deteriorate. Placed in the ground these animals would have disappeared. I acknowledge the gesture of taxidermy of trying to look at death in the eyes. The animals look really alive but they are truly dead. It’s this relation of life and death that is connected and condensed in these practices.

As you are mentioning this I feel like it relates once more back to Lebanon, or to any country that has faced violence, trauma, political upheavals or tough states; that parallel notion of living but also feeling dead from within; something you have referenced through your watercolours.

Yes, a series of my watercolour drawings are called 'Dead Inside’. I don’t look at it as a dichotomy of life and death, it is something that is already there. That’s why I named them ‘Dead Inside’. In french it translates as ‘La mort dans l’Âme’.

It can be part of a defence mechanism; sometimes we need to feel ‘dead inside’ because we cannot feel anymore, we are unable to, or we don’t know how to.

'La Mort dans l’âme' / 'Dead Inside'

2020, Aquarelle et graphite sur papier, oiseau naturalisé, Epingles à piquer.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès, Paris.

The series of watercolours started during lockdown, intensifying with the 4th august explosion in Beirut.

That feeling of something that died inside, it doesn’t overcome you and you don’t overcome it. You just live with the outcome and learn how to live with it. Personally, it is not just a metaphor, it’s lived experience.

'My Pain is Real'

Still from film; 3-channel video installation - Imane Farès Gallery - Paris 2010

That intensity was also brought into the cabinet of curiosities at The National Gallery. Federico Barocci’s painting ‘Madonna of the Cat’, features a beautiful goldfinch set in Christian iconography. That goldfinch has a red spot or marking on its head, which is said to have come from a fallen drop of blood from Jesus on the Cross.The goldfinch is beautiful because of that red colour. Taking in suffering, trauma, violence, accepting it, and turning it into something beautiful are part of these poetic imageries which we can all relate to. They speak of poetry through a religious narrative but not from a religious view, going beyond the religious construct.

The Madonna of the Cat, after Barocci, 2022. Goldfinch taxidermy and porcelain hand sculpture. "The bird in this cabinet references the goldfinch clutched by the baby Jesus in the painting by Barocci that was slashed by a knife in 1990" - The National Gallery. Commissioned by The National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme

Venice is filled with iconography and with poetry, you are showing at this year’s Venice Biennale, what is being exhibited and what is coming up next for you?

'The Dam' my fiction feature film, shot in Northern Sudan on the Merowe Dam on the river Nile will premiere in May in Cannes at the festival Quinzaine des Realisateurs.

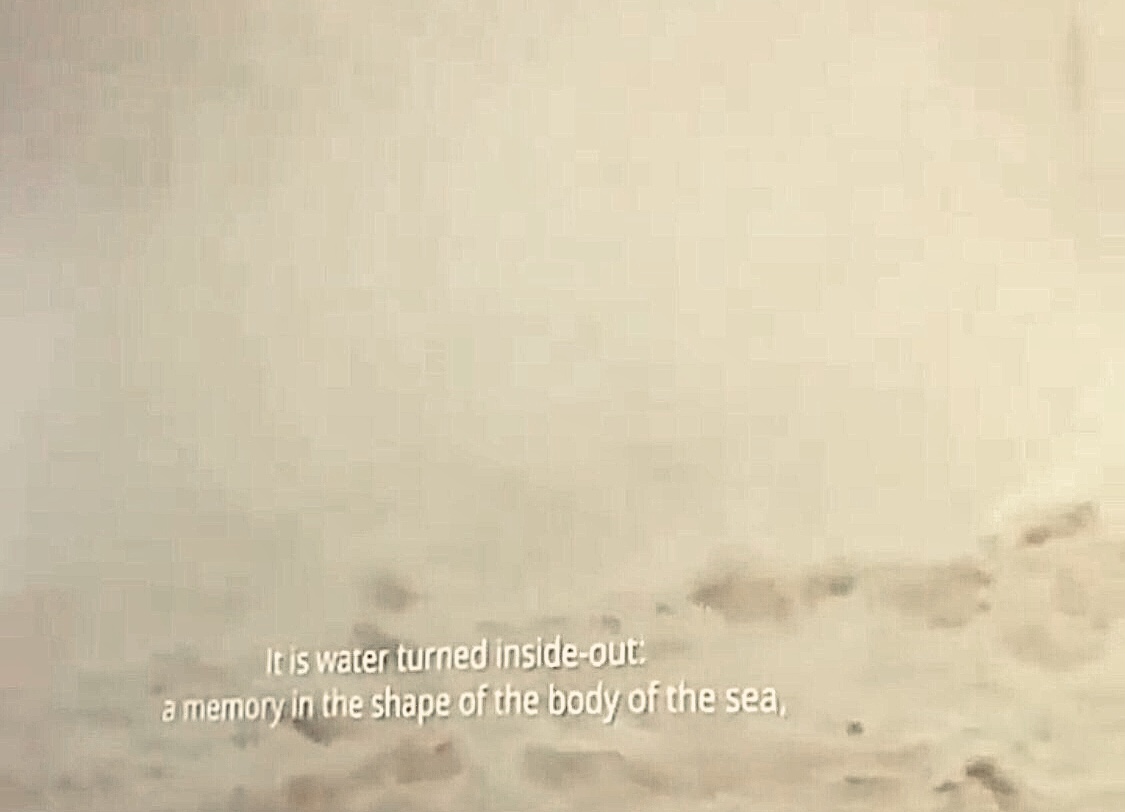

At Venice Biennale, a new three channel video installation entitled 'Of Men and Gods and Mud' was made from images that I shot mainly on a brickyard in Sudan. It can be viewed at the Biennale alongside new drawings of mud creatures, and three sculptural figures 'Titans' which are based on ancient deities.

Still from 'Of Men and Gods and Mud' part of "The Milk of Dreams" curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

'Titans' part of "The Milk of Dreams" curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

The exhibition in Venice explores the materiality of mud and how it comes together through earth and water.

It speaks of the mythologies around mud and the diverse religious beliefs of creation through it. Whether we refer to the biblical figure Adam, Enkidu, Golem, or so many other religious or mythological figures, humanity saw clay as the material of creation, where life came through mud.

Mud has a dual aspect; destruction or deluge happens a lot along the Nile, where muddy waters rise up, destroy and can even kill people, but mud is also the fertiliser that permits for the earth to prosper.

The soil, objects, life, war, history, all come with dualities, like above and below the surface we were discussing at the top of our conversation, my work searches in and through that, as dual aspects incite much of humanity.

'Titans' part of "The Milk of Dreams" curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

Ali Cherri awarded the Silver Lion for a Promising Young Participant in the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia: The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani. Picture © Gallery Imane Farès

Ali Cherri is a video and visual artist based in Beirut and Paris.

His recent exhibitions include 'If you prick us, do we not bleed?' at The National Gallery, London, and exhibiting ‘Of Men and Gods and Mud’ at the Venice Biennale where he was awarded the Silver Lion for a Promising Young Participant in the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia: The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani. He has also shown his work Phantom Limb at Jameel Arts Center Dubai, Immortality at the Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art Russia, An Opera For Animals at Parasite Hong Kong and Rockbund Art Museum Shanghai, But a Storm is Blowing from Paradise at Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan and Guggenheim New York, Somniculus at Jeu de Paume, Paris and CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain Bordeaux, Statues Also Die at Museo Egizio, Milan and General Rehearsal at Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Russia.

His work has been exhibited in several international exhibitions, among them Anarchéologie Centre Pompidou – Paris (2017); Lyon Biennial (Sept. 2017); Le MACVAL, France (2017); Guggenheim New York (2016); MAXXI, Rome (Nov. 2017); Aichi Triennial, Japan (2016), Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Italy (2016); Le Centquatre Paris (2016); Sharjah Art Space (2016), MACBA, Spain (2015); Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, Poland (2015); Es Baluard Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Palma, Spain (2015); Gwangju Museum of Art, South Korea (2014).

He is the recipient of Harvard University’s Robert E. Fulton Fellowship (2016) and Rockefeller Foundation Award (2017), The Abraaj Group Art Prize (2018 - shortlisted)

His films have been shown in International Film Festivals including New Directors/New Films MoMA NY; Cinéma du Réel, Centre Pompidou; CPH:DOX (winner of NewVision Award); Dubai International Film Festival (winner Best Director); VideoBrasil (Southern Panorama Award); Berlinale; Toronto International Film Festival & San Francisco International Film Festival amongst other.

Where do Birds go to Hide

Installation; Hand drawn fabric - Wood - Taxidermy bird - Variable dimensions - 2018

Ali Cherri / GALERIE IMANE FARES

Pictures courtesy of Ali Cherri and copyright © Ali Cherri

(Pictures of Ali Cherri's exhibition 'If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?' taken by nour saleh)