Brady Black

on the Power of Art, Street Art, Lebanon,

Reportage Drawing, Documenting and Art for Justice

Pen and paper in hand, Beirut based artist Brady Black has documented for the last seven years the Lebanon and mainly the city of Beirut. Through reportage drawing, he skilfully has captured the essence of what has been happening, drawing with each line the cries of a nation.

Through his drawings immersed in ink and passion, alongside his street art, Brady Black uses art as a voice, as a tool to ensure people are seen, issues brought to the forefront and concerns documented.

Emotions pierce out of Brady Black’s art, from the hearts of a civil society onto the pages of his drawings. Our conversation untangled the raw emotions felt, the hardship the Lebanon has gone through, the heartbreaking devastation, and Brady Black wishing to give something back to the country he has called home for the past seven years; as we started our discussion by unravelling through the effect of art…

What drew you to art and how has art impacted you?

I started making art when my mum became very ill and I had to take care of her full time. That was a mental health struggle for me, and so I started drawing.

Subsequently my wife was affected by depression and I just kept on drawing through that difficult situation.

Art has been an aid for me during tough times and my work stemmed from that.

I think art kind of saved me, including in this past year and a half in regards to the situation in Lebanon.

When did you come to Lebanon?

My wife and I came to Lebanon about 7 years ago, working in partnership with a residential home for children. Those children had grown up on the streets and around dumpsters, and they were placed in the home by the government.

We started a school for them, for children who had come from abused and abandoned backgrounds and had never had an education.

Can you share with us a bit about the school?

Many of the children had never had any kind of education, no previous reading or writing, even the older children, who were 11 or even 16 years old. Once we arrived and started the school, we discovered the trauma they all had, and how that early trauma can affect learning, behaviour, and cognitive abilities.

My wife began reading many books about that and consequently we ended up turning our school into an academy focusing on helping children through traumatic experiences by using education.

You document your surroundings through drawing, what is your process and what are the different emotions you go through? Can you tell us about documenting and drawing Lebanon’s Revolution?

I started documenting the Revolution because I had been working for 5 years all day and every day with people who’s life and experiences were the result of poor governance or policies.

For instance some of the children from our school had no identification papers, mainly because their fathers abandoned them and their mothers were not legally allowed to provide them with documentation.

My wife and I are in the in the process of officially adopting our son who grew up in the residential home for children, he never met his parents and has no identification himself, so I was and am surrounded by poor governance.

I very much felt a part of the pleas of the people; I wasn’t a tourist. I got bloodied on a regular basis during the protests, nevertheless, I also recognise this is not my revolution, this is not my country, however, I feel very sympathetic to it and I wanted to give something back.

The way I gave back was to draw the protests and give those drawings to anyone who would ask, any NGO could and still can use those images to showcase what was and is happening in Lebanon.

The art, my drawings are as a way of documenting, expressing what I saw.

It was important for me to draw Lebanon’s Revolution for both the people of Lebanon and for an international outreach, because at some points, it didn’t seem like there was much international attention being paid to the Lebanon.

I realise that as an outsider, I probably see things from a different perspective; as in what I am noticing may not be the same things a Lebanese person who is standing right next to me may notice, but that’s also why having several artists, photojournalists, or people documenting these moments is important.

At the beginning of the revolution, there was more of a friendly energy, with yoga happening on the Ring in Beirut and so forth, but then real injustices started to occur, people were getting beaten up and shot at. That was all taking place directly in front of me, and at that point I realised how serious and important what I was documenting through my drawings was.

I found that I capture different things with a drawing then with a photograph.

During a protest, I would be standing amongst all the photojournalists, who all thought I was crazy, as I would be sitting in the middle of things wearing a gas mask and drawing rather slowly what I saw. Many a times I had my drawings knocked out of my hand and stepped on, and that ended up all becoming part of the art.

We were carrying old men that were pushed unconscious, and as I had a gas mask, I was a part of trying to guide people away from the area that was being teargassed and shot at. The violence was really uncalled for, so for me, seeing that level of injustice, seeing the abuse of power, enhanced my feelings where my drawings became much more on par with the need to document what was happening.

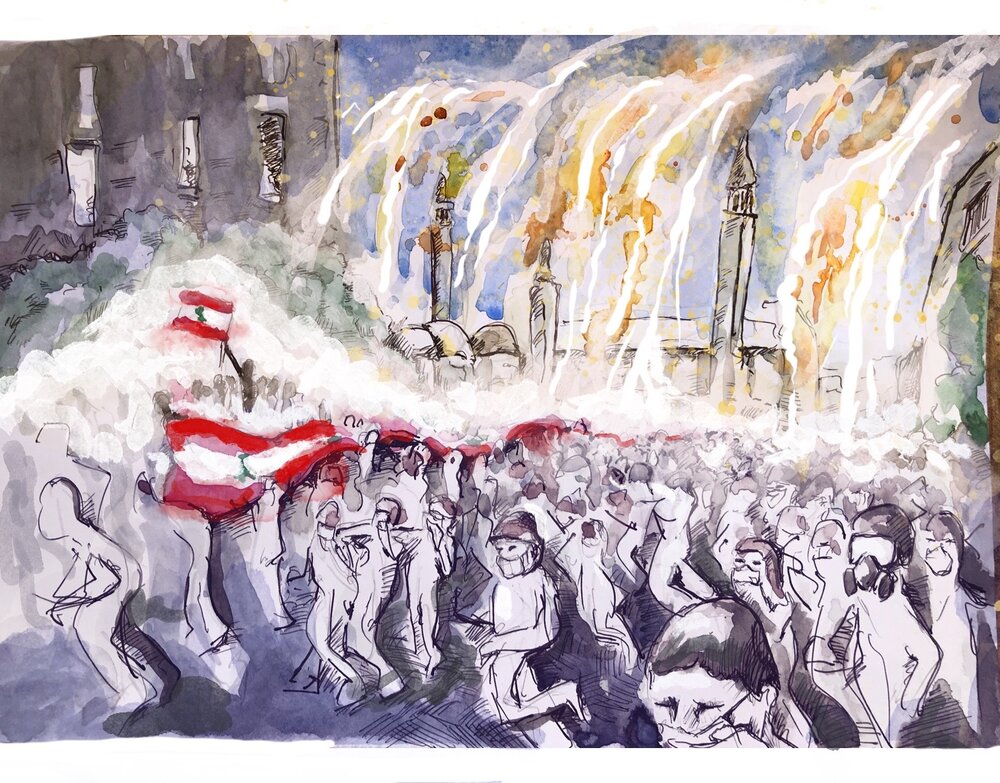

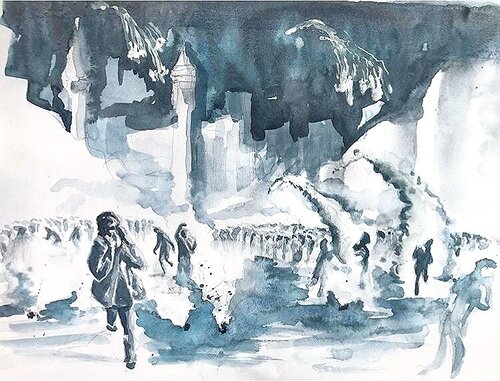

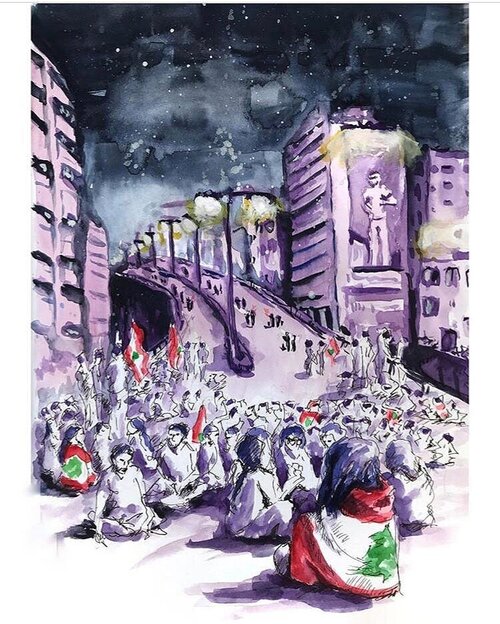

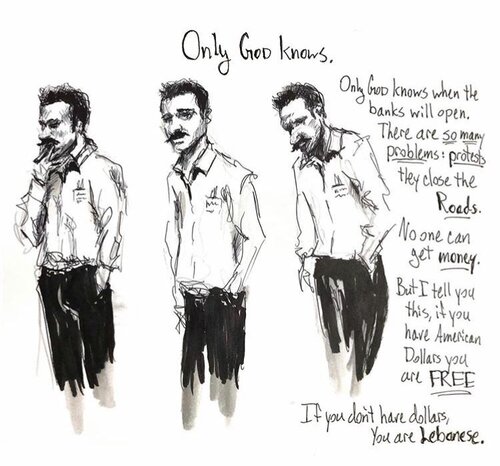

Illustrations by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series:

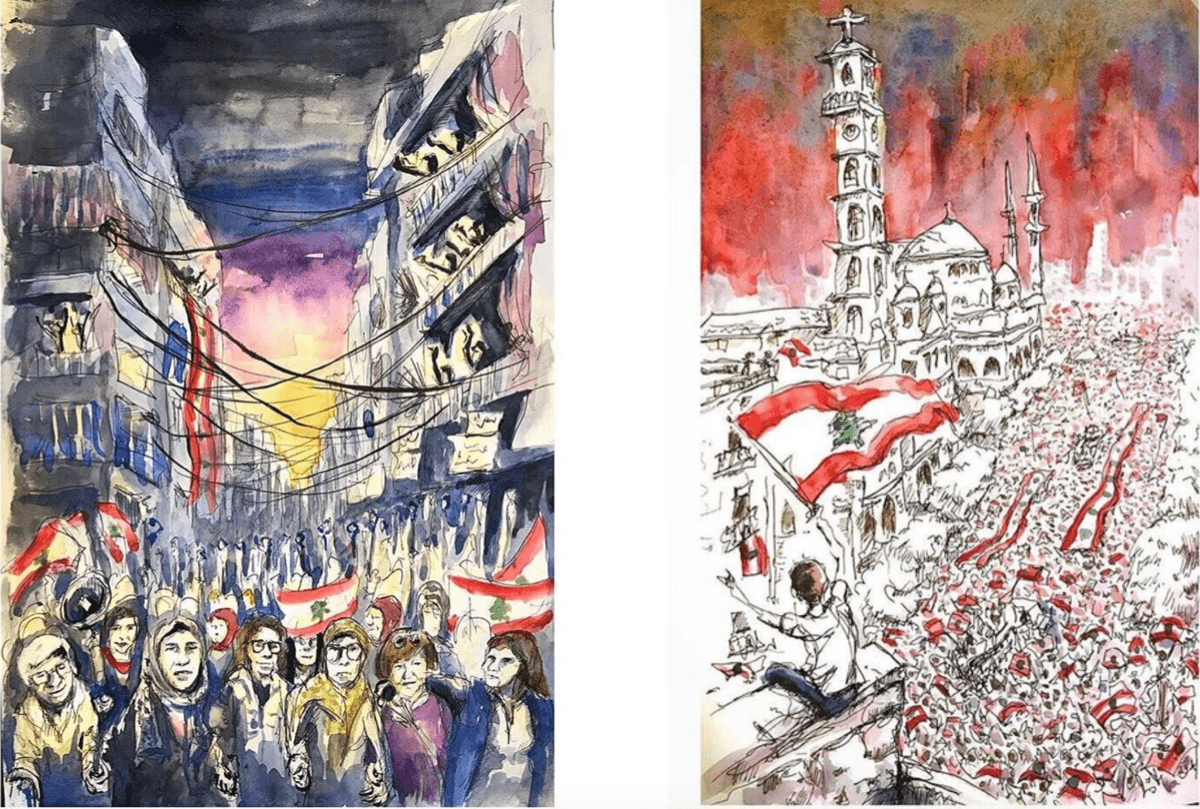

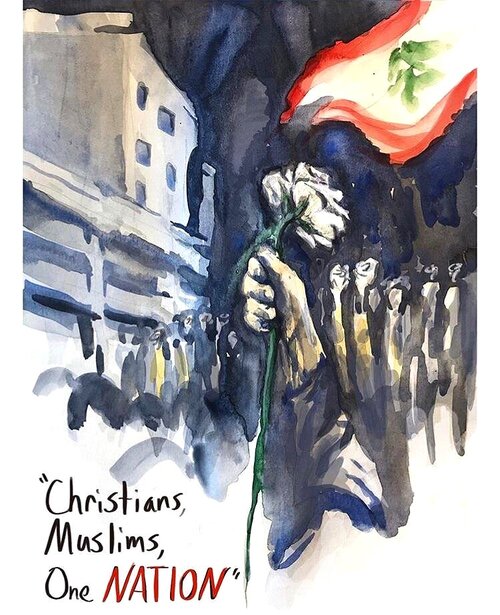

First image: the Mother's March in 2019: "as violence had been escalating since the start of the Revolution, the response of mothers and women were to walk and gather around the same place the Civil War had started ,holding white roses, candles, in the name of peace-chanting one nation" - Brady Black

Second image: Day 4 of the October 2019 Revolution.

Illustrations by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series, Mother's March 2019

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series

.jpg)

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - Battle of Beirut Night 2 - drawn on site

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - drawn on location during the first 100 days of the October 17th Lebanese Revolution.

Illustration by Brady Black from the Beirut Explosion Sketches no. 7 - drawn on site - "the first major volley of significant tear gas that began a day of 4 hours of continuous tear gassing." - Brady Black

What is reportage drawing? Do you draw exactly what you see, are there parts where you put your own feelings into the illustration?

My art is definitely not intended to be unbiased, and I am not held to the same standard as a photojournalist. Many of my drawings are a combination of scenes, I can understand Arabic well enough so a lot of words that I have overheard I write on the drawings, I also document time, sometimes I draw maps on the bottom corner of my paper, and through reportage drawing I am able to show movement and convey emotion. I try to capture the spirit or the feeling of the situation.

There are some occasions, where a drawing can grasp the impact of the day more accurately than a photograph. For instance, in this one situation, where a row of men had blocked roads and access to an old square, a photograph wouldn’t have been able to capture in one shot the different rows of people on both sides. When I am drawing, in this case for instance, I can highlight the multiple scenes occurring on both sides of the line, the different tensions, emotions and atmosphere that are happening at the same time.

I intentional try and provide the viewer with a bigger picture and an essence of what is going on.

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - Nejmeh Square protests - Night 2 - drawn on site

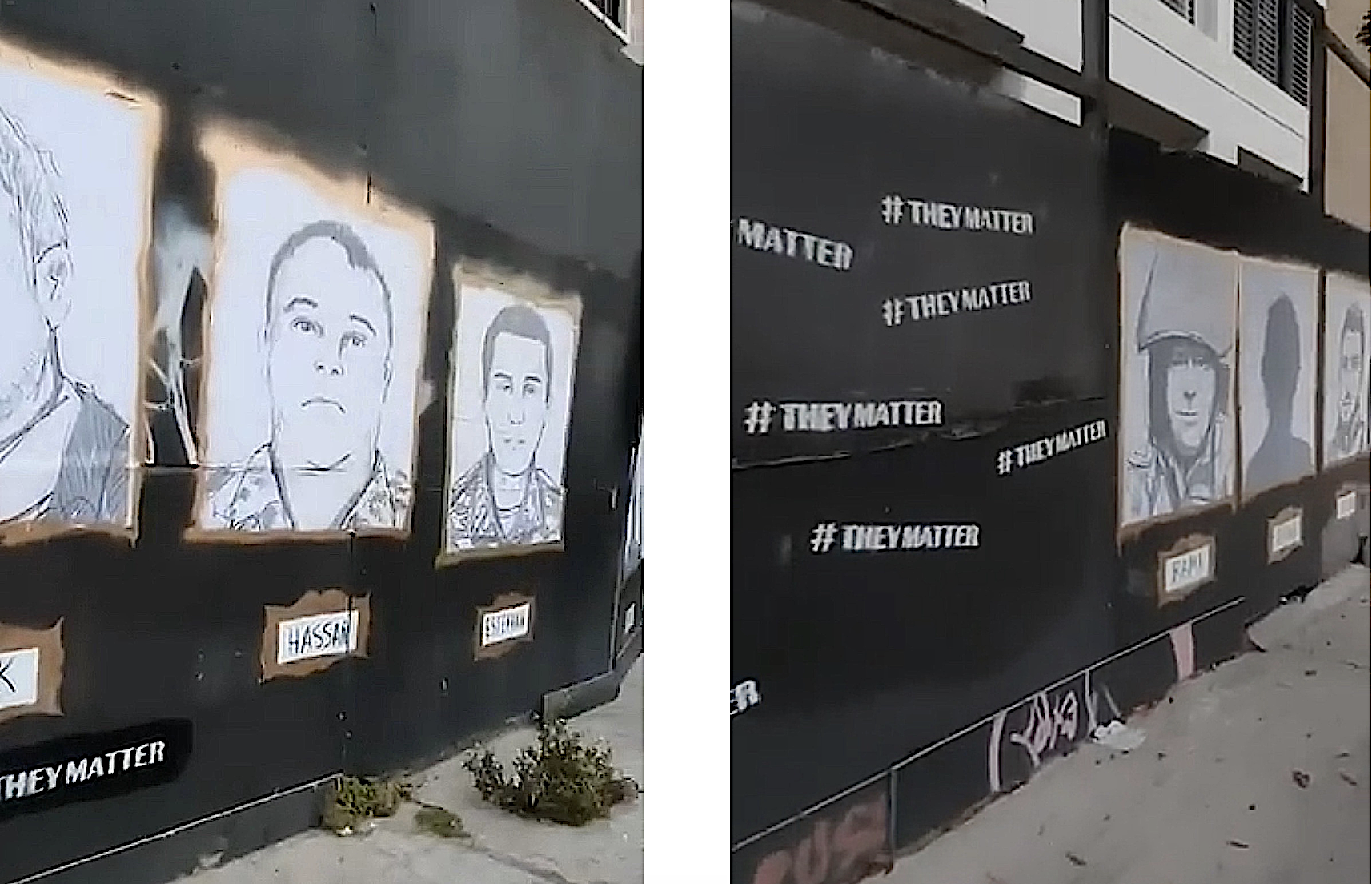

On the 4th August 2021, it will be one year since the explosion in Beirut, with no justice yet for the victims. You drew the portrait of each victim, in memory of those lives, with a hashtag #theymatter.

I have to admit I was struggling with formulating a question, because words were failing me, only immense sadness for what happened. They matter, they really do, they always will. Something had to be done, it’s good you were able to do what you did.

Could you talk us through how you drew the portraits of the victims, its importance and your emotions throughout.

I’ll start at the beginning of it.

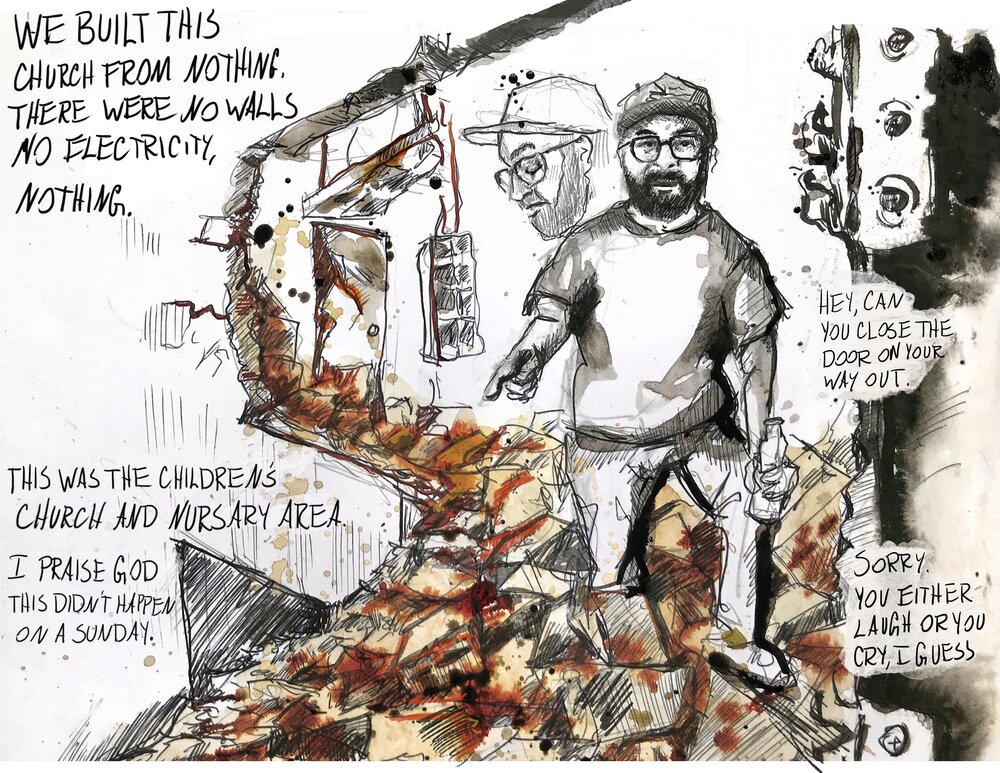

We were in Lebanon on the 4th of August. My best friend’s place was extremely damaged, we all were walking around like zombies, many were covered in blood and my Church was absolutely destroyed.

I was there, I lived through it.

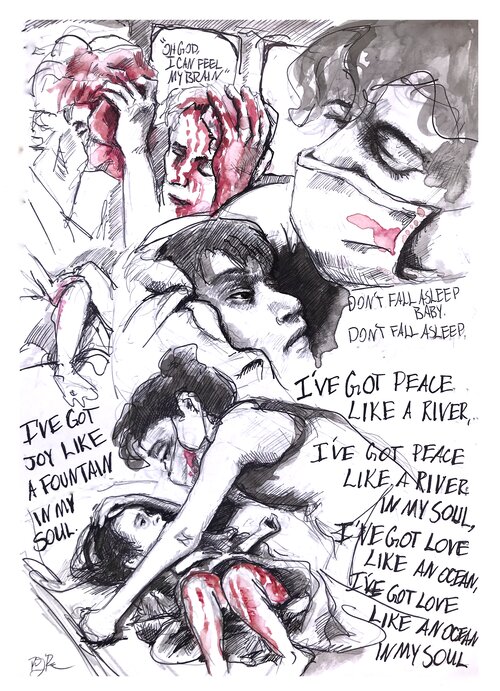

Illustration by Brady Black from the the Beirut Explosion Sketches

Illustration by Brady Black from the the Beirut Explosion Sketches

Illustration by Brady Black from the Beirut Explosion Sketches. " She carried her daughter and ran after a leaving ambulance. Trying to calm her daughter she sang softly inside the chaotic ambulance full of people crying and moaning in pain. The ambulance was so packed, that no paramedics could even fit inside. All of this was drawn from first hand video and thankfully her daughter was ok" - Brady Black

.png)

Illustration by Brady Black from the Beirut Explosion Sketches - "Hundreds of people descended on Beirut with their weapons of shovels and brooms to help clean their city." - Brady Black

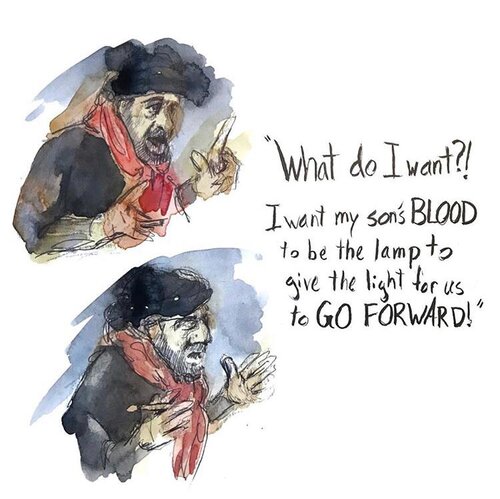

When the families of the victims protested, I saw them carrying their loved ones’ pictures, holding on to them tight, crying. The pictures were of their sisters, brothers, their daughters, theirs son, fathers, mothers, and I kept seeing that image of the families holding on to the pictures over and over, and they mattered to me.

I really wanted to do something for them, for them to be heard and seen by everyone.

Much of my other work is about drawing what may be visible but for some reason chosen not to be seen, and making people and social issues be seen by all. If you draw someone you are taking time to do so. We are all surrounded by images all day, we see so many extreme things, but when someone takes time out to draw a person, it can make people pause and reflect. And that’s what I want with my work, to make people visible, to make people on the edge of society who are not normally seen, be seen. People everywhere matter, children on the street, they matter, each person is a soul.

So when I saw the victims families, their cries for justice, it profoundly touched me. Because they all mattered, and I thought why don’t I just draw all of the victims.

But I had no idea what that entailed.

I ended up partnering with Art of Change, they helped me with the logistics, research and motivation as well, because it took months of drawing full time, and that was exhausting not just physically, but spiritually.

I spent a lot of time drawing the victims eyes, I would pray for the families, pray for justice, I was doing that for months, and it took quite a tole on me. Drawing them became very difficult at some points, I hadn’t at first thought of that, it was more about doing the project and its importance.

I drew from a combination of multiple photographs. Each victim’s eyes are all intentionally looking at the viewer. Starring right back at you. I Intended to make it uncomfortable. The idea was to have the eyes ask for answers. We owe it to the victims, to answer them why and how this tragedy happened.

Some people understood that message, others have been quite offended by it; but that people can’t always look at the portraits, means it touched a nerve.

At the same time of honouring them and the families, we are also reflecting the families anger, reflecting through the victims eyes, through their portraits, the injustice of what happened.

Thankfully, the families have been supportive of the portraits, they have either felt honoured or they understood what I was trying to communicate.

The families are amazing.

Initially when we put them up, we didn’t have any permission for it, we didn’t have permission from the families, we didn’t have permission from anyone. We felt this is what needs to be said, but we didn’t know how people would react. There was a possibility that it could have been taken poorly, but we accepted that; myself and Art of Change, we thought to ourselves, if this goes wrong then we just listen.

We ended up recruiting a team of 40 volunteers, it was all very secretive, we didn’t tell them what we were doing, where it was, but we gave them a general idea and told them that there was no permission, that they were taking some risk. With that team, we installed the whole thing with home made glue, in about 1 hour and 40 minutes.

Each portrait is large in scale to communicate the scale of the travesty, the scale of the injustice, it’s 300 metres long and to walk around it would take a good 15 minutes.

After the installation, I spent the next couple of days finishing each portrait. Following that, with the team of 40, we turned the drawings into a portrait gallery.

The portrait gallery comprises of frames created with gold spray paint around each poster drawing of the victims, with hand written names on a placard. It is meant to give the idea of a museum, in other words, the idea that these portraits shouldn’t be there, that it is unfinished, that they should be done in marble or be oil paintings.

When you look at one portrait you don’t necessarily see another one, though they are installed one next to the other. It was done intentionally so that we have to contemplate with intent with each individual; because each one of them matters.

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

Alexandra Najjar was only 3 years old when she was injured from the explosion, and heartbreakingly passed away 72 hours later. Firas al Dahwish was the director and art handler of Agial Art Gallery and Saleh Barakat Gallery and was very sadly injured from the debris of the explosion, passing away a couple of days later.

.png)

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

Jean-Marc Bonfils was a Lebanese-French architect who had worked a great deal on rebuilding Beirut after the Civil War, he was fatally injured in his apartment on the 4th August and very sadly passed away.

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

Sahar Fares was one of the first paramedics on the scene, a fire brigade who tragically lost her life due to the explosion. She was about to get married.

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

2 year old baby Isaac Oehlers heartbreakingly passed away on the 4th August. Gaïa Fodoulian was a Lebanese-Armenian art gallerist and designer who also worked to support the region’s artists and designers, she heartbreakingly passed away on the 4th August.

.png)

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

Elias Khoury was 15th year old and very sadly a victim of the explosion.

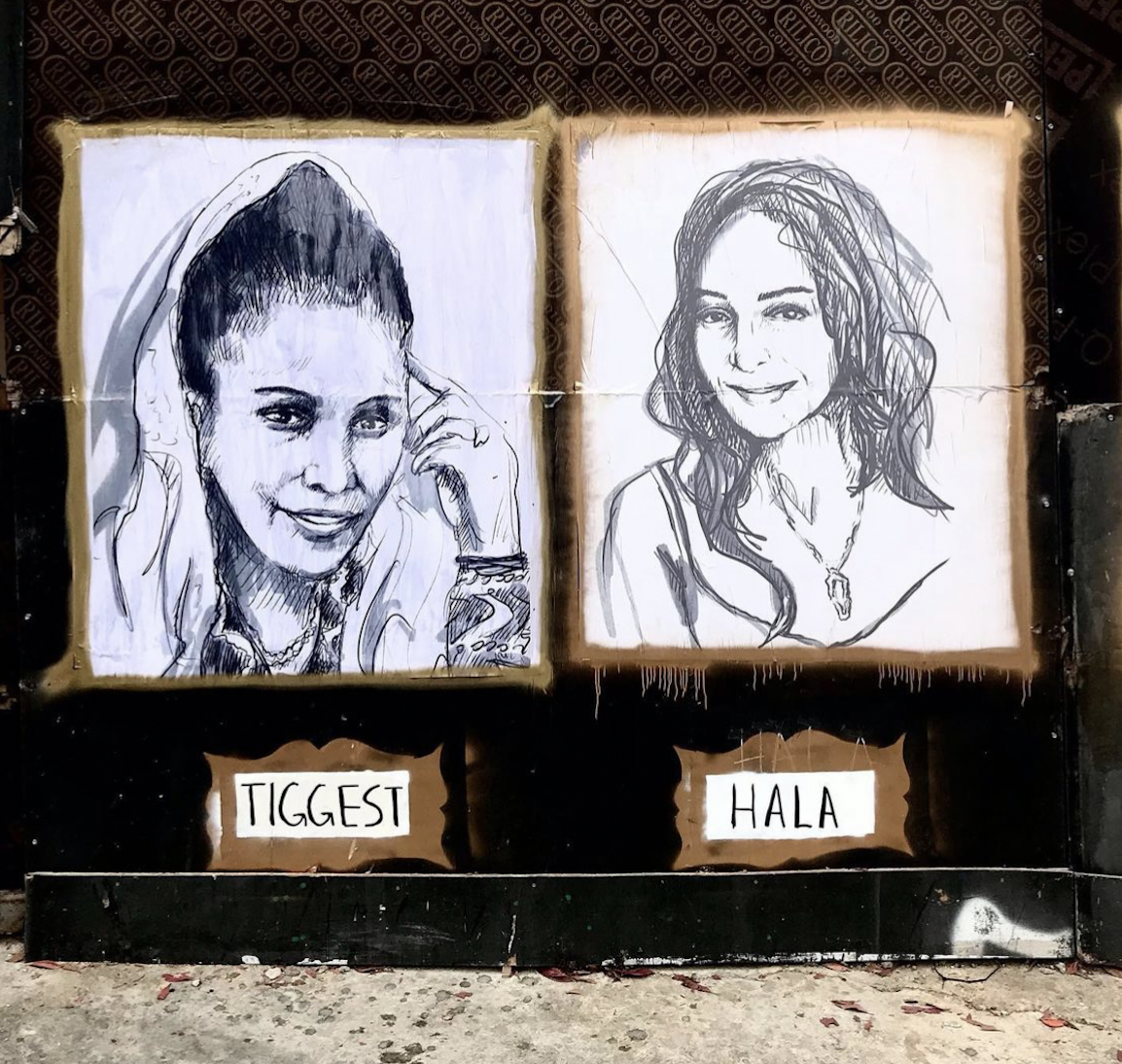

Photograph from the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

"Tiggest was working in Beirut to pay for her 17 year old daughter to go to school. Thankfully the family she worked for contacted us to make sure she was on the wall." - Brady Black

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

THEY MATTER

Still photograph from clip of the They Matter portraits illustrated by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change.

These portraits drawn by Brady Black in collaboration with Art of Change are just a few of the 204 portraits done in memory of the victims of August 4th. Brady Black adds more portraits when he receives information or images of the victims.

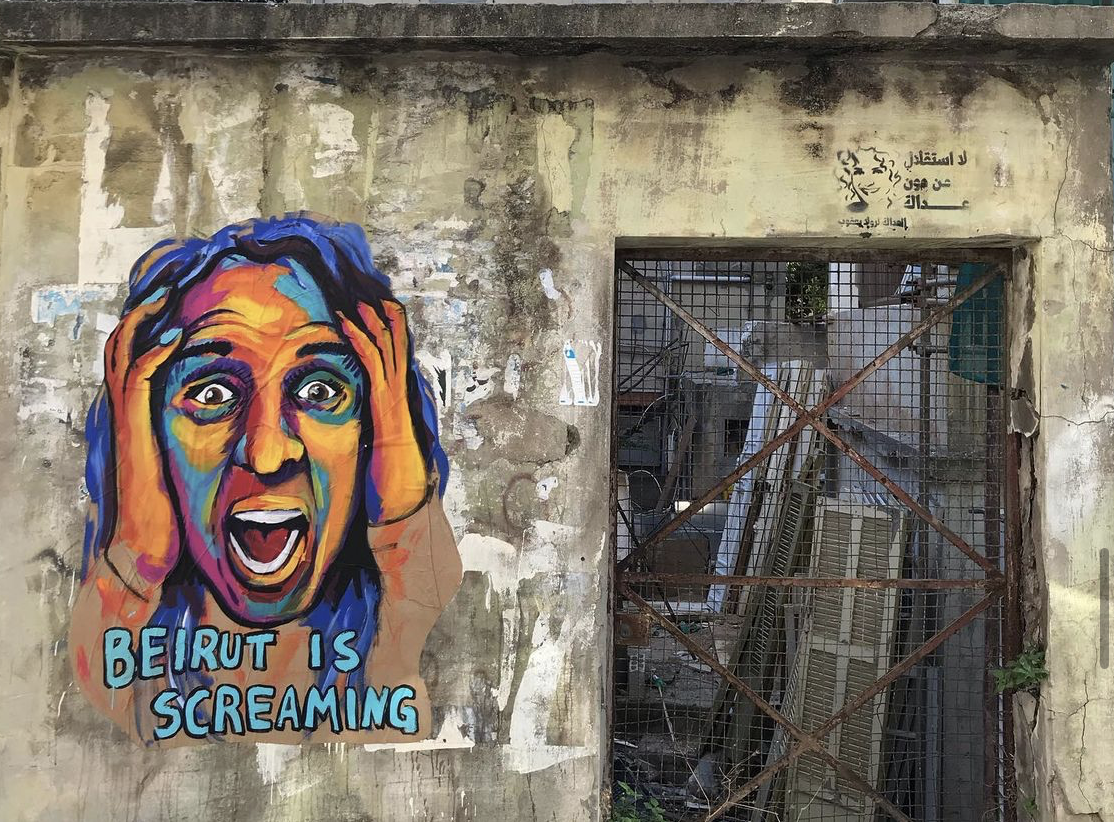

Can you tell us about your street art?

I do street art and public art. When I first started out, I tried very hard to get hired by magazines or newspapers, but I couldn’t get many of the publications to pay me for my drawings, that led to a bout of depression, which in turn propelled me to start drawing on walls.

My street art practice was able to continue with Art of Change who have been really supportive of me, helping me try to create a space to discover what public art was about. During that time, I really fell in love with the idea of street art and public art, mainly because the children I really care for don't always have the opportunity to go to art galleries, many who live on the street, they too are not going to galleries, and I want to communicate art to everybody. Furthermore, I don’t have to deal with an algorithm, or worry about likes or follows.

Art reclaims public spaces. Most in Lebanon have very little access to food, and yet there are still giant billboards advertising luxury watches or giant mayonnaise jars staring down at us, and all I kept thinking was why is that happening, and so I thought well, I’m going to start putting my images up and communicate things that I see or hear, trying to find and showcase the voices that are around me, and also sometimes my own personal opinions, especially when it’s dealing with children and hunger.

"Corruption" illustration/poster by Brady Black

Illustration/Poster by Brady Black from the Brady Street Sketchbook series no 31

How much power do you think art has? Lebanon’s walls have been for so many years covered with political posters, do you see art as adding a perspective, its own layer to the fabric of the city?

Art has a tremendous amount of power.

That’s how I see it. My art is a little slow, I can’t do it that fast. With street art, I am taking a cue from the city, posters are everywhere, so I am just adding mine. I am not advertising a party or a politician, I’m just speaking through art, asking to pay attention to certain important notions the country has been crying out for.

Though art can have several aspects to it, we have consistently questioned if and put forward on this platform, one of our motto's and aims, that art can unite, do you think it can?

I think it can.

I would like to create symbols with a message that we can have a collective experience.

Studying symbols, we can see how they can become larger than us. Take for instance the peace sign and all the symbols from different movements, a collective idea can be created through a symbol.

But I think that it can be a divisive idea or a uniting one. It depends on what the message is. I am going to try that experiment with symbols soon.

You have lived in Lebanon for the last 7 years, what would you like to share about your time in the country?

I love it here, I love the people, I love the country itself.

It’s just so messed up, I have no idea myself how to fix it or how it goes forward.

It’s not my job to do so as much as it is to stand next to somebody who is trying to figure that out.

I just want to stand with the people who are seeing how to do that, and I try to, as much as I can through my art.

.png)

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - Day 41

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - Day 30

Illustration by Brady Black from the Revolution Sketches series - The father of Hussein Al-Attar martyr of the Revolution

Illustrations by Brady Black. "I drew the original "Finjan" (coffee cup) back in October (2019) when everyone was much more hopeful.

I redit it (on the 11th August 2020)."

These illustration were also part of from the "Beirut We Love You Project" with Art of Change

Brady Black is an artist working primarily in pen, ink and watercolour with a focus on direct observational reportage illustration. Brady immerses himself in the situation and experiences the story while drawing live on location. Brady was born in Texas, USA and now is based in Beirut, Lebanon with his wife, son, and their dog Kreacher. Exhibitions include, “Kuh-rupt” - Art of Change Gallery-Beirut, Lebanon & Cairo, Egypt -2019-2020; “Revolution Sketches” (solo show) - Hook Gallery. Beirut, Lebanon, 2019; “Pop of Hope” - Matisse Gallery. Beirut, Lebanon, 2019 and “Face to Face” - Tout Gallery. Beirut, Lebanon in 2018. Brady Black has done some illustration work for UN Women, and been published in several newspapers and magazines including Sorbet, Selections Magazine, L’Orient Le Jour and An Nahar Newspaper. He also runs Serious Creatures: art workshops and lessons for children.

.png)

"Things I saw: Beirut. Petrol station swarmed by people trying desperately to get 1/4 tank of gas. Some waiting for as much as 4 hours in the summer heat" - Brady Black