Dominic Chambers on

Cultural Memory, Identity,

Art that builds Bridges,

Community, Figure Painting, Colour

and Hope

Dominic Chambers photographed by artist Shikeith

Dominic Chambers love for books has impacted his work, with his art referencing various literary narratives as well as mythologies and African-American history. He explores all these notions through the everyday, whether on moments of reading, leisure, contemplation or meditation.

His art enables a conversation on how societal constraints may result in erasing parts of people’s history. Dominic Chambers art readdresses those history pages, ensuring they are seen and heard.

His use of the figure and of bold colour draws the viewer into his enigmatic paintings, to discover a magical world as well as that of realism, and branches of love and hope. His artworks bask between the real world and his imagination.

Dominic Chambers’ art is filled with layers of meaning and history. Viewing his work, meaningful ideas develop out from his use of light and shadow, as well as his composition. His paintings are mysterious, yet beam with visible and non visible light.

Captivated by his use of colour and references, we asked Dominic Chambers to share his thoughts on art and on his hopes...

When did you first get into art and what does art mean to you?

I first began my exploration into the realm of art in high school. I was completely obsessed with the art classes at my school and my teacher, Robert Sralla, took a completely different approach to teaching art to high school students. He didn’t teach our class passively, but instead treated us as individuals who could potentially pursue a serious career in the arts. Introducing us to professional criticism and art historical references. It really changed the game for me. My experience in that class taught me that art was something that helped me connect with other people. Art was a way that I could introduce myself and allow for someone to attempt to understand who I was beyond the words that I could share. That’s what art means to me: Art is not only an intellectual practice, but a medium that can build bridges between different groups of people.

I'll Be Your Shadow You Be My Shade

You graduated from the Milwaukee Institute of Art and then from the Yale University School of Art, can you share with us a little about your time at each institute, and how did your art develop throughout?

Before speaking about my time in undergrad and graduate school, I must first acknowledge my time at Florissant Valley Community College and it’s profound impact on my life. Flo Valley was located in the Ferguson neighborhood of St.Louis and had the first nationally accredited art program for a community college in the state of Missouri. While there I was exposed to a deeper understanding of the artworld and was pushed into a more contextually aware studio practice. The program was rigorous and deeply enriching.

While at MIAD (The Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design), I had a bit of trouble finding my community. I transferred into the program at the junior level and so, I was the new kid in the school. However, with time, I built an incredible relationship with my professors there who took me under their wing and invested additional time to helping me develop my ideas and offering more critical and at times, brutally honest feedback to my work. I was actually making minimalist monochromatic paintings at the time. Work that, in retrospect, wasn’t necessarily the most visually engaging but conceptually promising. My professors there saw something in me and nurtured my desire to pursue my career in the arts much more aggressively. I actually only spent three semesters at MIAD. The reasoning being- that while at MIAD, I was awarded the Yale Norfolk Summer residency, in addition to the New York Studio Residency Program. Both in the same year. These awards were critical in helping me develop a foundation for pursuing my graduate studies and gaining a deeper understanding for what it meant to work and live as an artist. Norfolk was quite intense. However, the most immediate change to my studio practice can be traced back to the six weeks I spent at that residency. I ended up abandoning the more minimalist approach to painting in favor of more complex imagery in hopes of opening up a broader conversation that I felt I needed to have with my work. The impact of both residencies still influence my studio practice and outlook on the world as an artist to this day.

While at Yale, I struggled with my studio practice more so than I ever have before. I explored, failed, and revised my studio practice numerous times while completing my studies there. It should go without saying that Yale is a highly riguous place. The numerous times that I failed in my studio, and the emotional and psychological stress that comes with the program, made for fertile soil to grow an enriching and more complex studio practice. The results of the impact Yale had on my studio practice is evident in the work that I am making now.

Work from exhibition "These Brief and Spirited Things"

Your artwork looks at cultural memory and identity, how do you approach these two notions?

I read a lot. I love reading about african american history and the stories written by african american writers. I also try to take time to catch up with myself when I can. For me, the opportunity to reflect on your culture, and who you are, and who you were is an invaluable tool for furthering one's art practice. I try to offer works that display refreshing ways in which we can associate to the black identity or question what our collective societal identity is. The figures in my work are with us in these moments of contemplation.

In those moments of contemplation, when you explore the body in your art, what exactly through it do you want to relay?

I think, for me, I am less concerned about body politics and more so the politics surrounding the context in which we find particular bodies. It is no secret that the history of representation does not do any favors for the black body. Furthermore,in regards to art history and within the historical narrative of the United States, the black body is always located in a problematic or objectified position. Some examples include: existing as a status symbol for white wealth in paintings or located under the lens of criminality and servitude within the historical narrative of America. I aim to examine the context in which black bodies are found. My approach is to create images of black bodies resting, reading, contemplating, and sleeping within an environmental context often not afforded to them. There is no genre of art history that locates black people as intellectual beings. There is no historical context that locates black bodies in America that as people who contemplate, who read, who rest. Because that has not been our historical position and we weren’t allowed to pursue knowledge or engage with any sort of intellectual activity. I want to make images that change that and utilize the reading material that I have to influence how my images are constructed and contextualized.

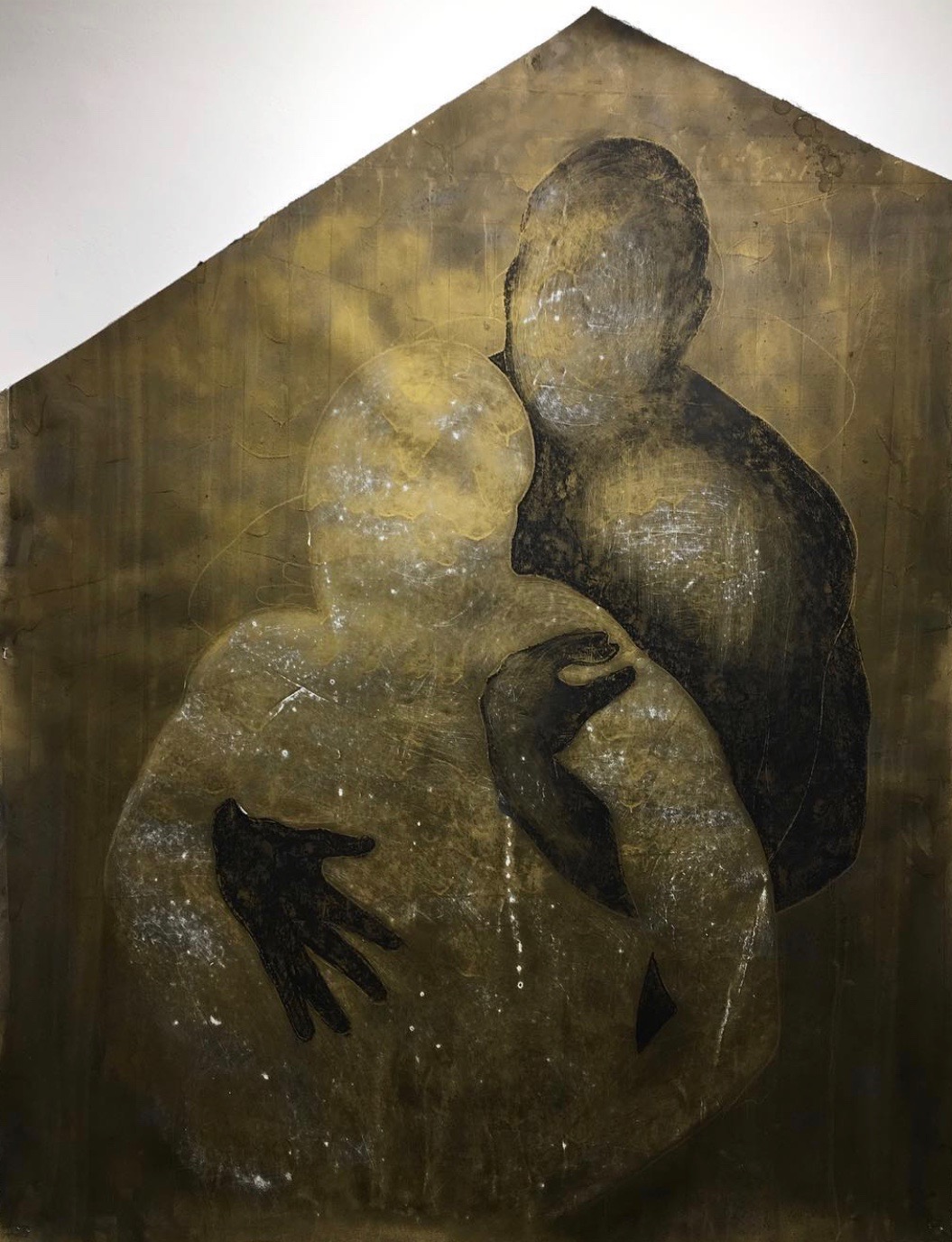

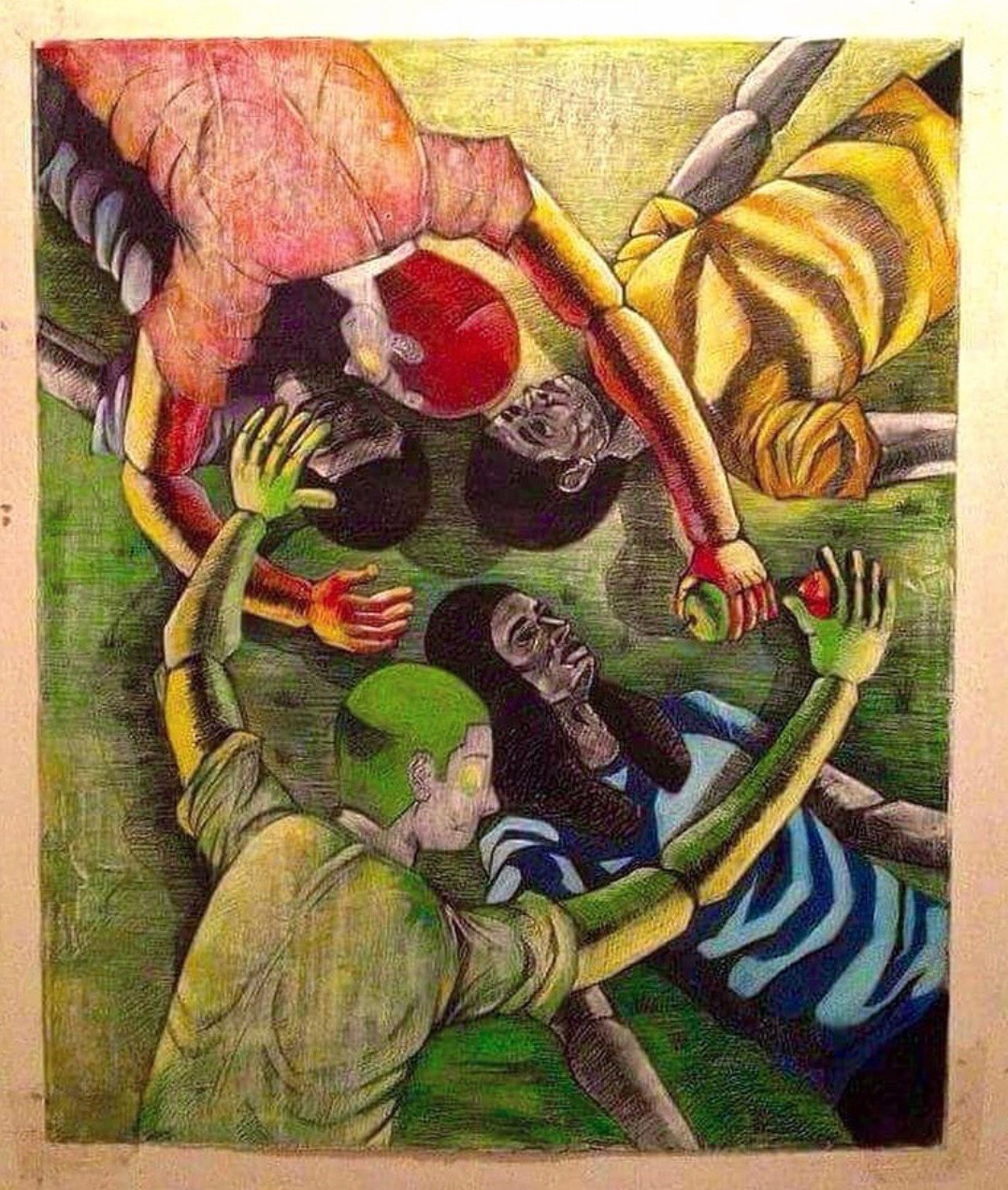

Works on Paper

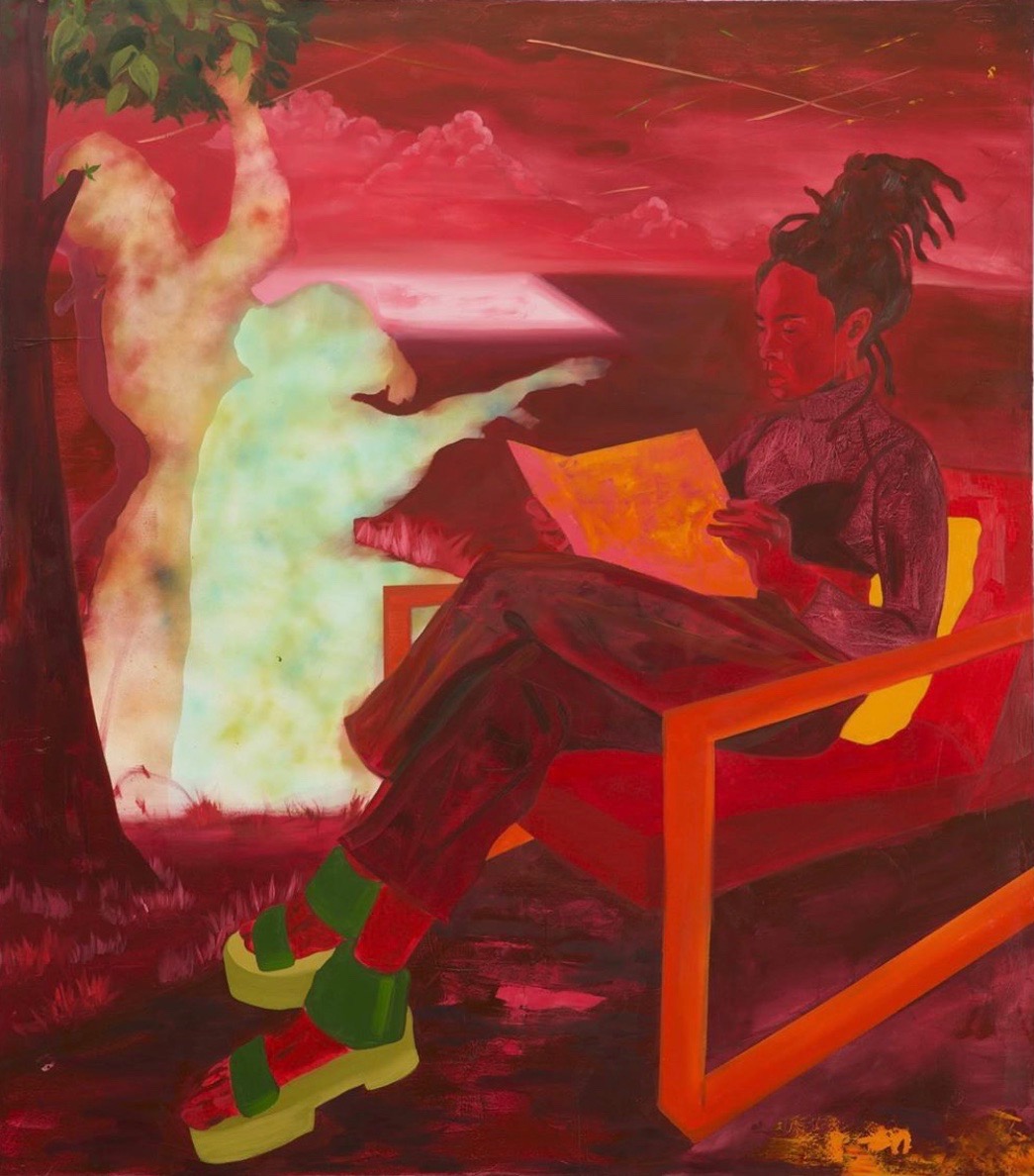

Your paintings, such as ‘Blue park lovers’ or ‘Life is elsewhere’ delve into magical realism, combining elements of your life with symbols and metaphors, when did you first establish that essence in your work?

I was first introduced to the genre of magical realism when I read “ 100 Years of Solitude” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I loved how Marquez utilized surrealism to explore the complexities of Colombian life and the experiences of the characters in his stories. However, The book “ The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao ” by Junot Diaz remains the biggest influence to my approach to magical realism in my work. Junot Diaz utilized magical realism to discuss real world historical events and how it can influence the lives of the fictional characters in his story. I loved that. Because surrealism certainly has its place within the African Diaspora and the African American historical discourse. I learned to combine magical realism with other literary works like: The Souls of Black Folk b y W.E.B DuBois. Dubois describes the Veil and Double consciousness within his book. The veil is not a literal thing at all, It’s a sociopolitical phenomena. The veil is the curtain that separates black people from white people and in some cases, each other. It is because of this veil that the fullness, beauty and complexities of blackness are unfathomable to the white population and as a consequence- to black people themselves. Filtered through the lens of magical realism, one must acknowledge that the veil is not a tangible thing, instead it is something that is felt. The feeling of living within a veil is what's real. It’s a strange and surreal experience.

Blue Park Lovers (Kev & Ashley)

You recently referred to reflecting on colour and perception as well as looking at Josef Albers’ work, what are your thoughts on perception relating to colour? The colour blue seems prominent in your work, what does it represent for you?

The interesting thing about Albers that separates him from other artists who have worked with color is that his primary approach is not an investigation of how light moves and affects color, but how perception influences how we perceive color. I think that is a beautiful metaphor for how we often engage with people of color because it is because of our perception of how we view skin differences that influences how we are more or less likely to treat someone. For me, I wanted to utilize my time of quarantine to explore these ideas. I am not sure if I’ll continue it as an ongoing investigation, but it has been something I’ve been curious about for some time.

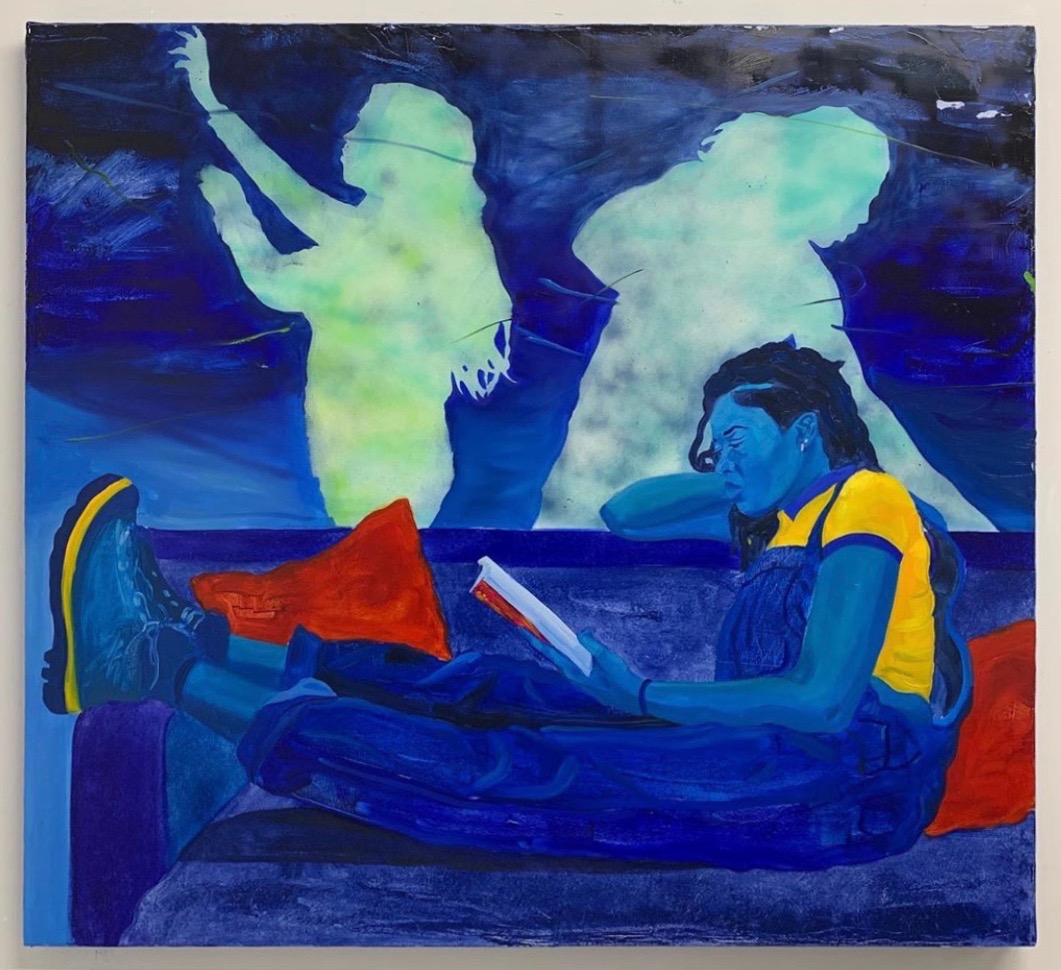

As for the color blue in my work, I think that there is a misunderstanding about its importance to me. I use it often, yes, but I would like to clarify its role in my practice: The blue paintings I make aren’t special in any particular way. They are part of a body of work I call the “ Primary Magic” Series. They are a series of figurative paintings that explore magical realism, leisure and color utilizing one of the three primary colors as the dominant color for a given work. There are red, yellow and sometimes black monochromatic paintings as well. Although, my audience seems to be quite fond of the blue works.

Life is Elsewhere (Max in Blue)

Something came to Me (Moses in Blue)

Send it On

The Sweetest Thing (Adrienne in Yellow)

Dark & Beautiful (Catherine in Black)

Art can be a tool to readdress certain narratives and add new narratives to the discourse. How much power do you feel art holds?

I think that art is an incredibly effective tool for change. It’s a very slow tool, to be sure. Art presents ideas that need to marinate for a while before they influence our thoughts. It seeks that whenever we find ourselves uncertain or at a loss for words, art seems to be the thing that a lot of people return to. To me, that means something.

You have mentioned that you hope to work more with your community, do that art can bring people together and how much impact has your hometown had on your art?

Art can bring people together, it allows for us all to engage with an object, have different experiences and those experiences are equally interesting. Some of the best debates and conversations I’ve had have been around how different our experiences are when engaging with a particular artwork. There is no room to say that someone's engagement with something is wrong, but instead space is created to empathize with why someone may have that relationship to the artwork to begin with. Considering our current social and political climate, that is profoundly important.

Red Sky Visitors (Kenturah in Red)

Meditation in Blue (Malia by the Water)

The world is going through COVID-19, there are unfortunately many heartbreaking stories, as well as many who are re-evaluating what as a world we tend to value. What are your hopes for the future once we get through this pandemic and what are your thoughts on how art can help us grasp the notion of value beyond its monetary intent?

My hope is that people start taking the lives and positioning of vulnerable people in our country more seriously. If the economic and social disparities present during the COVID-19 pandemic have been an indication of, it is that collectively we have a lot of introspection and restructuring to do. I hope that we re-evaluate what is that we personally don’t want to give up, in order to better the lives of those less fortunate than us. I believe that art could be a great vehicle for these kinds of things. With accessibility to artworks, people are exposed to history, the lives and stories of interesting artists, love, and themselves, in a more vulnerable sense. The good thing about art, is that it forces all of us to slow down. From then on out, we can begin to reflect on ourselves, the world and each other. At least, that’s how it could help, perhaps in a more romanticised way. But, that’s where I’m at.

What are you working on next?

Next, I am working on my solo show at the Anna Zorina Gallery: All this Life in Us. Stay tuned.

Open Air

Ain't Nobody Here But Us (what love looks like)

Take off the Blues (Kevin & Ashley in Blue)

Dominic Chambers grew up in St. Louis, MO and currently works and lives in New Haven, CT. He holds an M.F.A Candidate from Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT, a B.F.A from Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design (MIAD), Milwaukee, WI and an A.F.A from St. Louis Community College at Florissant Valley, St.Louis, MO. Solo exhibitions include "Black Boys, Landscapes & Magic", at The Millitzer Studio and Gallery, St.Louis, MO and "These Brief & Spirited Things" at The Residential Gallery, Des Moines, IA. In 2015, he held a residenct at New York Studio Residency Program, Brooklyn, NY and in 2015, at Yale University School of Music & Art at Norfolk, Norfolk, CT. Dominic Chambers has been awarded the Yale Norfolk Ellen Battell Stoeckel Fellowship (awarded through MIAD) and the New York Studio Residency Program (awarded through MIAD) in 2015, a Varsity Art XVIII Award, STLCC – FV and Transfer Scholarship, MIAD in 2014 and the Board of Trustees Scholarship, STLCC – FV in 2012.