Uplifted by Break Down

Breaking Down Consumerism

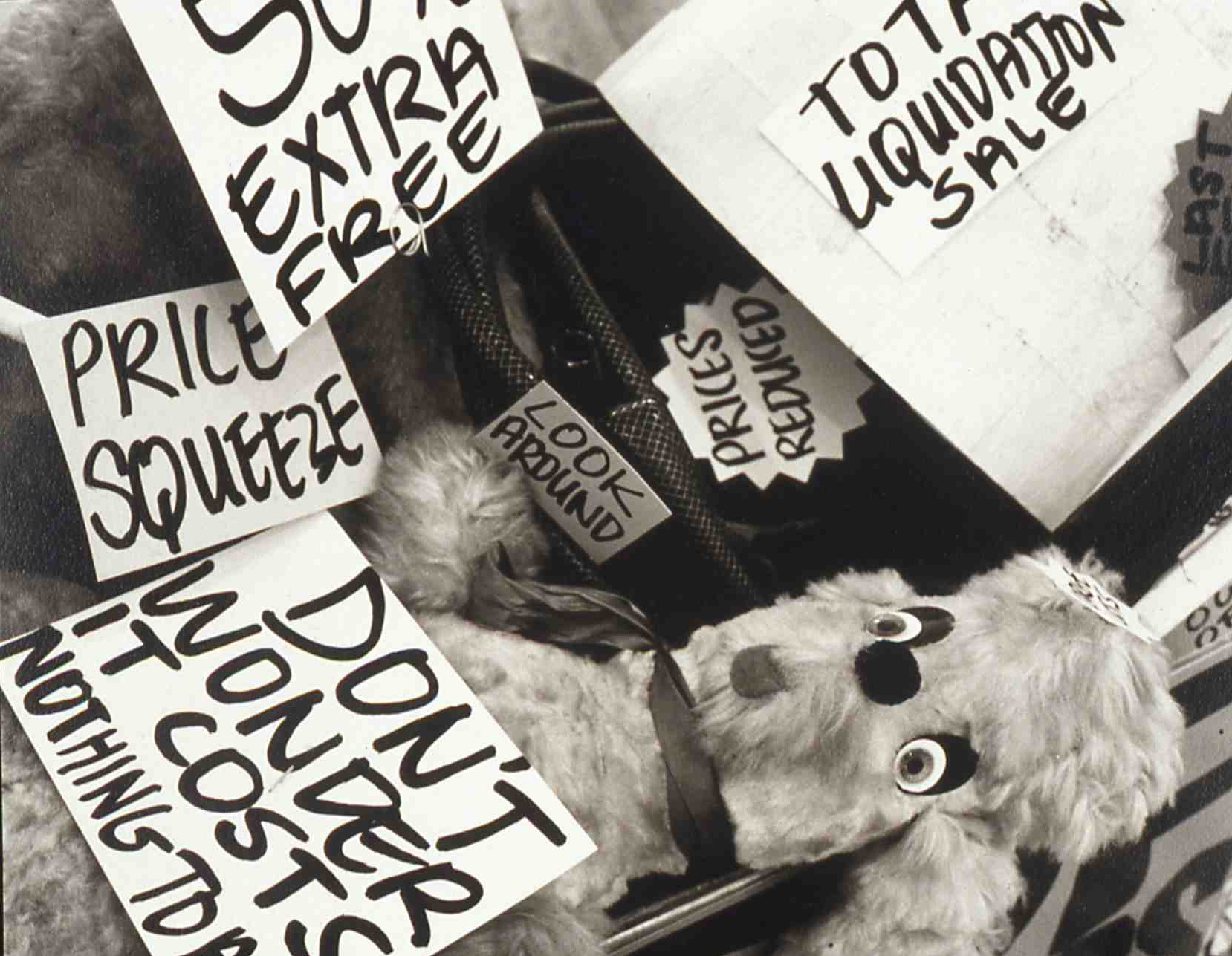

Michael Landy, Closing Down Sale, 1992. Installation view, Karsten Schubert Gallery, London

Michael Landy’s work makes us think, step back from the everyday realm and question what we take for granted or view as norms.

He tackles in his artworks the notion of consumerism and identity that engulf us on an almost daily basis.

His art as food for thought could be a remedy for our consumer souls.

It’s not everyday you meet a man that has rid himself of all his worldly belongings, but that’s what happened one morning in London. Sitting coffee in hand at the Brown’s Tea Room, I waited for Michael Landy to appear, even though he had declared himself dead to the Royal Academy.

As far as I knew that was only a temporary death.

Landy was elected as a fellow to the RA, because, as he would later tell me, Tracey Emin had asked him, and he was “too frightened to say no”.

I couldn’t help but recall the exhibition “Sensation” at the RA in 1997 with so many different art genres in one space. Michael Landy, one of the original YBA’s (Young British Artist), had one of his pieces bought by Saatchi and featured in that exhibition. Once we started talking though, I discovered that he didn’t, and doesn’t so much feel at home with that moment. He does however fondly recall his time driving round in his Beetle with Damien Hirst when they, with other artists, set up Freeze in 1988.

Michael Landy had though, first studied textiles because he could not justify going into art, “coming from a working class background” he wanted and needed a job, and despite being disturbed by some guy “hammering daffodils on a board”, with “no empathy for fabric”, he found himself at Goldsmiths studying art.

As Landy portrayed that “the world is much more of a visual place than it was”, the conversation turned towards the ever more present blurred lines between fashion and art. Sharp boundaries do sometimes exist for some amongst different fields of creativity, or perhaps for others, diluting them together used to be more frowned upon, but for Landy he appreciates “breaking and blurring, that’s a really interesting thing, like when fashion designers become artists or when artists start making clothes, I think that’s a good thing”.

This openness to creativity extends towards his openness to others. He cares about society and about his art students, how they struggle to live in London, the hardships they may face as artists, and the chances they may or may not have in their future.

Landy uses his creativity to share his thoughts on social, political issues, as well as on the self, reflecting them in his artworks.

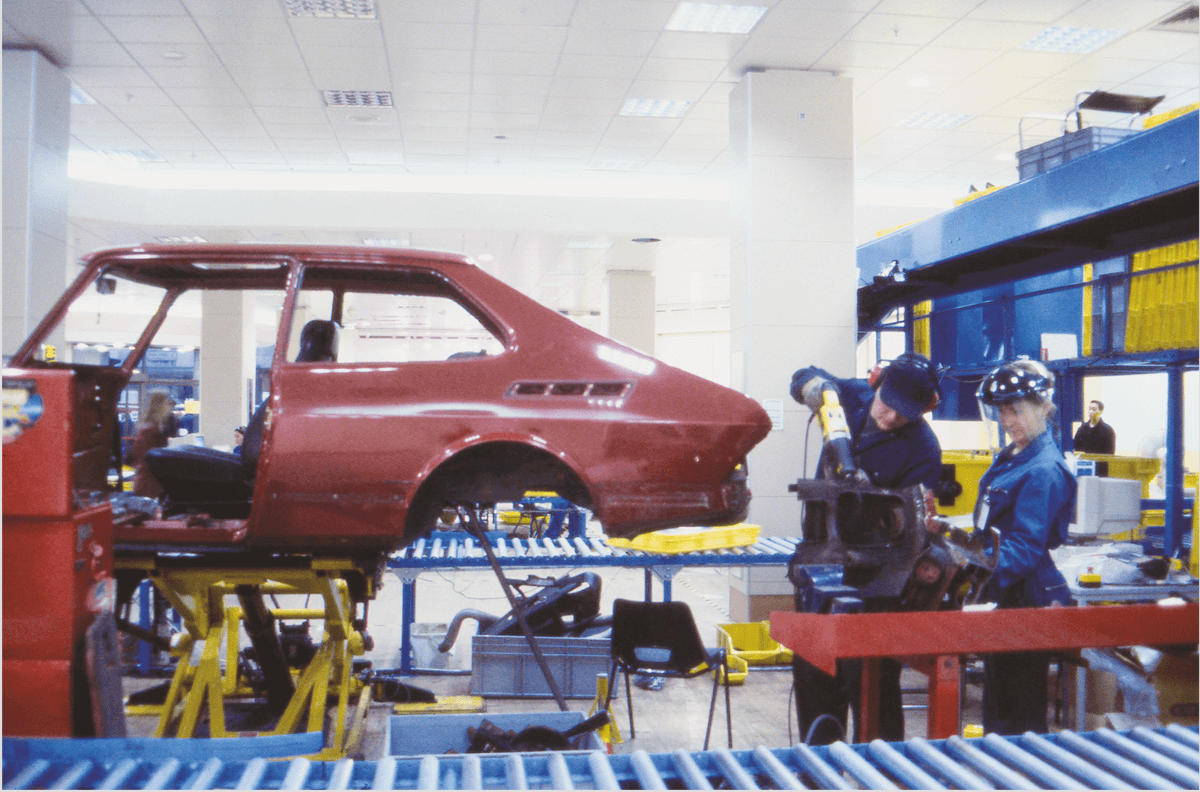

Amongst his many thought provoking artworks Michael Landy produced Break Down in 2001. A gathering of all his possessions, placed in yellow trays circulating on a conveyor belt, aided by assistants and ready for destruction, all in a sort of industrial made up site housed in the now closed C&A branch on Oxford Street. Items included his car–a Saab 900, his father’s sheepskin coat, artworks and personal notes. The process of smashing, shredding and general destruction took two weeks.

“It’s an artwork, it’s not a way of life” someone had told Landy. And yet, that artwork, those two weeks, have now lasted a lifetime, as though the artwork cannot be resurrected in real-time as such and not counting the imagery and inventory that has kept the process alive, the relevance of the work is still within our consumer fuelled society.

As the conversation on his artworks and on having a creative perspective on life began, Michael Landy told me that he “used to say during Break Down, a commodity is an ideology made material” and I guess that commodity, is still nourishing the ideology.

Fuelling thoughts.

What emotions did you feel during the process of Break Down?

Paranoid….and happy as well – all sorts of emotions.

I felt ecstatic, it was the happiest two weeks of my life and at the same time, I was a bit paranoid. You are witnessing your own death, people you hadn’t seen for years turned up, that would only turn up at your funeral. During Break Down, I had my mum crying, so I had to throw her out, because I couldn’t deal with another crying scenario and because my mum, she would also cry at my funeral. There is a sort of sequence of events that are supposed to happen, normally she is supposed to die before me, so I had a real mixture of emotions.

It took me 3 or 4 years actually, to get to that point with Break Down, so it is also a celebration. As an artist, I make sense of the world through what I create but it is also my self-identity.

I recently went back to C&A, which is now Primark, you see people go around pushing their trolleys, just chucking in clothes that they don’t even try, they don’t even look at them because they cost something like a fiver or tenner, so all these people are just wheeling their trolleys around.

I have talked about Break Down as an examination of Consumerism.

As a child I used to like taking stuff apart, taking my toys apart, as I wanted to know how things worked, and that’s how I’ve talked about consumerism.

In Break Down we really stripped everything back to its own material, all 7227 things I owned at that point in time, at the age of 37. We tried to reveal consumerism on Oxford Street, which obviously is the best place to have it. Oxford Street was and still is, the Mecca of shopping, people go there to shop, they don’t go there to look at art.

During Break Down people would steel things, people would offer me money for parts of my car, things like that don’t happen at art galleries.

There are only certain times, that as an artist you get out of the art world and into a broader world. I mean C&A is a place where people go to consume, that is what was interesting. People work their whole lives to have things, and so ownership and the possession of things are all part of what makes us human and there I was destroying it all in front of them.

On the whole I had a very positive reaction, it kind of restored my sense of the British public because people where very inquisitive, and wanted and still want to know what motivates someone to do that. They also talked about their own feelings of ownership and self.

I have never made any piece of artwork before, or probably ever will, where so many people wanted to talk about it, which was very interesting. We spent a lot of time talking to people, they were really engaging in it, and that is ultimately what you want to do as an artist, is engage the public. When it’s an exhibition, no one says anything, you do it anyways, but you don’t get any feedback – it is as if you are in a vacuum – apart from maybe your friends, family, loved ones, and they are most of the time biased.

Well you tapped into something, because we all own possessions

Living in the West you end up with stuff whether you want to or not, and the more money one has, the more successful you are perceived to be in our society, so the more stuff you have, the more that is the case.

I guess that at the age of 37, or a few years that preceded that, I wanted to think about why is that so important, because for the first time in my life, I was ahead, I had a car, I had a flat, I had things. Then suddenly I thought, well what does that mean, and it just popped into my head that I should destroy all my worldly belongings. But the process began with just phones, VCR’s and televisions. Obviously, things, possessions, a love letter, a family heirloom, a family photo, they all have different sorts of values, and within that – not necessarily monetary values.

Do you feel now that your relationship with the 7227 objects that you destroyed are stored in your memory? How do they now exist for you?

We made a list but obviously you can’t wear a list, you can’t eat a list or you can’t drive a list but we did make an inventory of everything I owned at the time, so we literally identified everything I owned into different sections.

How do you now perceive these items you once owned, do they all live in your mind, do you think about them much?

No, not really, they got landfilled so I completely landfilled them in my head as well. I made a purposeful effort to do that – very controlling really.

Like the way the destruction happened, everything got broken down into its material parts. It was quite meticulous, and all that occurred over a two week period. So people saw things in different guises, it being broken down, then shredded and grinded, and then it all ended up in a landfill somewhere in Essex.

I knew what was going to happen, so it’s an abstract thing now – It’s quite a long time ago.

Someone said to me it’s an artwork it’s not a way of life and that for me, was a good thing to say, because it was an artwork, and I created it as an artwork.

At the same time, I was the perfect person to sell to, because I didn’t have anything – I did look at compulsive obsolescence…

.png)

Michael Landy, Break Down, 2001. Installation view, C&A building, Oxford Street, London

In your artwork, were you also referencing that we possess more than what we own? In a sense, even with nothing we have a lot we have our integrity

Yes we do, I think we are more than the sum of our parts.

Actually that cropped up afterwards with the artwork Acts of Kindness on the London underground. It refers to when we don’t have the economic means to offer material things, we have our kindness and humanity to offer, which actually gets overlooked a lot. People don’t even notice they have those elements but they are being kind and humane to others without even realising they are doing so.

I think that is what came out of Break Down too. People were really kind to me and really open and when I literally had nothing I started to think, what makes us human, and basically that was humanity and a connection between a person and a complete stranger, that kind of emotional bridge between the self and other.

When I had nothing, that didn’t last, someone gave me something within the space of 2 minutes and I felt churlish to say no I don’t want that, because that would have been rude. But Break Down was not about that, my artwork was about people coming and experiencing a man destroying all his worldly belongings in front of them.

The only thing you can’t take away from people is the experience itself. That’s what I really wanted, for people to take away the actual experience of Break Down, to look into the trays and see things moving around which were probably similar to what they own or to something they had just bought down the road from Oxford Street.

We are all now linked and taking in the experience of technology, we seem to be consumed by social media or selfies

That is the self, partly one can see it as narcissism but also at the same time that is an interesting phenomenon.

I am not really into social media.

I guess it brings people together the way art should or can do

Ultimately in the end it could be like I said, just the experience of it.

Your artwork Art Bin is also an experience and also raises questions on value, possessions, as well as on being emotionally attached to items

It is about artists and failure. Obviously, as a creative person I am used to that, part of the creative process is failing, but one doesn’t see it as failing as such, you just know it, it is a stepping stone to somewhere else. No one ever sees artist’s failures – not in that form anyway. So it was a celebration, a monument to creative failure.

Art Bin was about artists throwing their ‘failures’ into a giant 900 cubic metre bin in south London Art Gallery. It was also open to owners of artworks.

A lot of people and some well known artists didn’t want to do it, for all sorts of different reasons – understandable reasons, but I guess I saw it as a celebration of failure, and I like the idea that people who threw artwork or their own artwork into the bin, were making one thing fall on top of the other, their possession would then get lost, and so the whole story and narrative would change everyday.

When I read about it, I felt as if you were creating a kind of mini

revolution – liberating in some sense, a form of empathy to Break Down, because in a way, people were doing what you had done with Break Down

Yes in a way it is liberating, some people just had the artworks and some people had stopped being artists, had locked their doors, not knowing what to do with their former selves, and so the process was part liberation as well.

Allowing people to throw things away, throw it into a skip, wasn’t purely a negative thing, it was a celebration of failure. I think artists understand that.

Did you have a list as well?

Yes we had a list of the people who took part and there was also an online form that you had to fill in, because during Break down I destroyed my own art work and I destroyed my friend’s artwork, which at the time I didn’t realise that the property laws in this country (the uk) about ownership are, that if you are an owner of an artwork, you can destroy it but you can’t turn it upside down, you can’t change its colour, you can’t misrepresent it, but you can ironically destroy it – so that kind of cropped up.

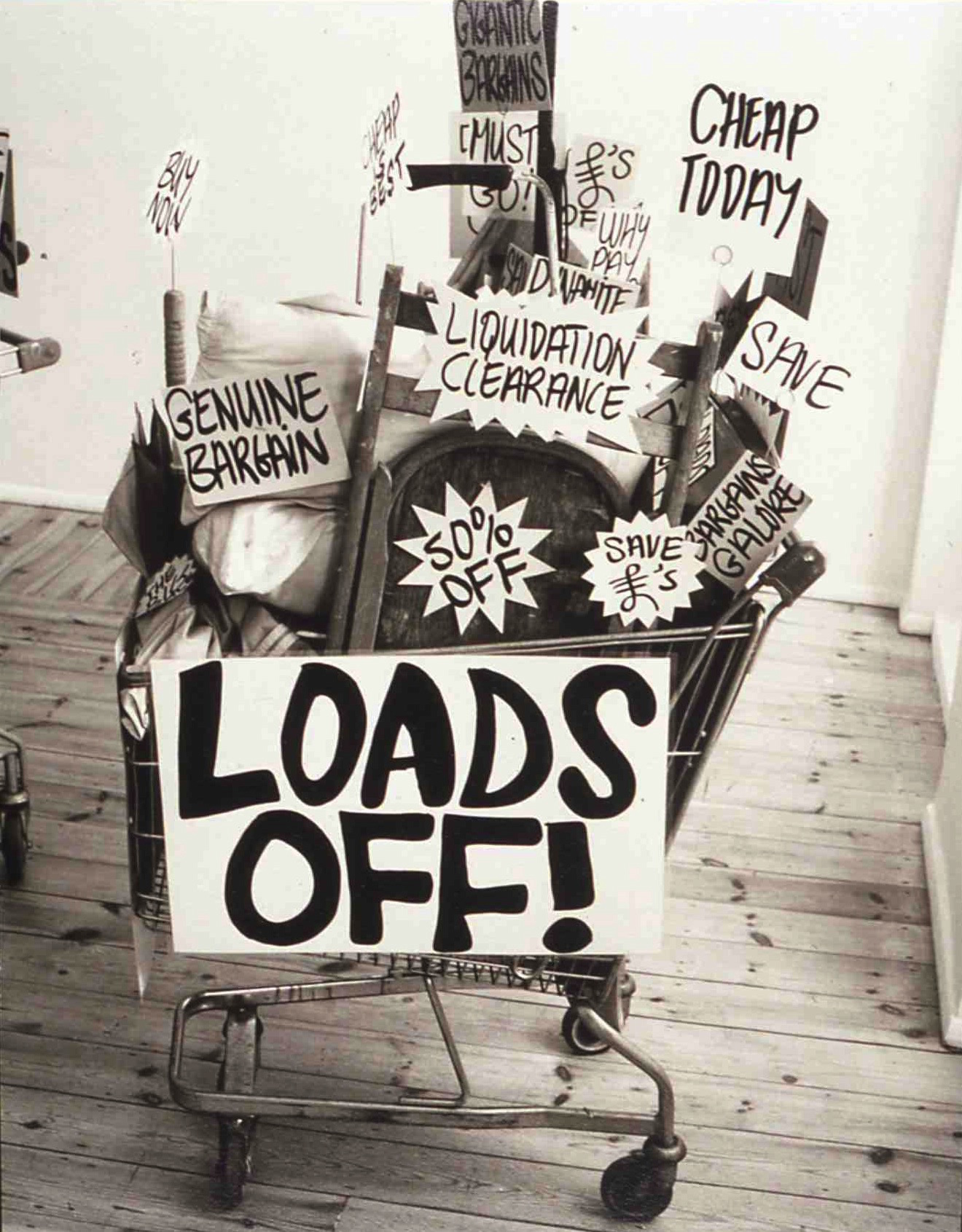

Closing Down Sale as an artwork also covered consumerism and maybe it can also now be read as a reaction towards people buying art or things as a commodity. More and more we are seeing that

I guess that what I understood of collectors when I first started to show work outside Goldsmith, was that collectors were people who collected artworks but they would never sell it. Now it is much more than that, things have changed, now auction houses are also galleries. It’s all got very confusing, all the lines are blurred, collectors buy and sell things, so it’s more like speculation, and that’s because of the amount of money that is involved now.

I have never actually been to an auction myself. I should really go along. Whatever people are prepared to pay for it, is the price of it – that’s what my friend Helen would say. I take it very personally, because I can’t separate me from what I do – the two things are inseparable.

Closing Down Sale was actually my reaction to a recession. London at that point in time, back in 1992, looked like what I turned Karsten Schubert gallery into. So basically what I was doing, was selling people the stuff they’d thrown out, rubbish they’d thrown out; it was full of mattresses and teddy bears.

I put the stuff into shopping trolleys and then had them festooned with kind of fluorescent ‘For Sale’ signs all over them, but I was really literally trying to sell people rubbish.

I am interested in value because obviously, value is always changing the whole time, it is not static, it is a very malleable thing. Things you own ultimately end up in landfills, or sent to the rubbish, but then some things will go beyond that, and they end up as antiques.

I think value is always changing, and most of the things I destroyed during Break Down would have ultimately ended up in a bin somewhere anyways. The interesting thing too, about that artwork, is that people would also make a kind of assessment about me as a consumer.

Do you think in a way value has a lot to do with power, to a certain extent, as an artist you have power, showcasing aspects on life and society, that as viewers we might not have noticed

I don’t know, I think what an artist can do, is obviously look at value, why we find it attractive or not, and maybe look at the whole system value. I guess that’s what artists do, but they do it in a slightly illogical way. I think I have always been interested in value and labour and worth, whether that is of a human being or of an object, or a weed.

Between all this conceptualisation, it is easy to forget that Landy is also a brilliant drawer. The weeds that as he mentions he sees value in, have been the subject of his drawings and showcase him as a skilled draftsman. As do his drawings for the artwork Breaking News, part of which, covered the Brexit deliberation.

In 2016 Michael Landy’s exhibition ‘Out of Order’ at the Tinguely Museum in Basel spanned his career.

As a student, the work of the artist Jean Tinguely and his sculptural machines, had left an impact on Landy and in 2013 after a two-year residency at The National Gallery, Landy’s exhibition Saints Alive engaged the public through kinetic sculptures that in turn were inspired by paintings of Saints from the museum.

One of those sculptures was that of St Francis, a Saint renowned for giving away his worldly goods. Entitled St Francis Lucky Dip, it was operated by a push-button and on occasion produced the prize of a

T-shirt with the words: Poverty, Chastity, Obedience.

All part of a day’s work for Michael Landy, pushing our thought buttons and giving us concepts to take away in a nondisposable manner.

For more information about Michael Landy and his work visit Thomas Dane Gallery in London

www.thomasdanegallery.com/artists/43-michael-landy/works/

All pictures are courtesy and copyright of Michael Landy and Thomas Dane Gallery

Michael Landy

Born in London, 1963

Lives and works in London, UK

Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988

Solo Exhibitions

2017

Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece

2016

Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.)

2015

Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio,London, UK

Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2014

Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico

2013

20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK

2011

Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia

Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK

Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK

2010

Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK

2009

Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France

2008

Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2007

Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.)

H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.)

2004

Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.)

2003

Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany

2002

Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK

2001

Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.)

2000

Handjobs (with Gillian Wearing), Approach Gallery, London, UK

1999

Michael Landy at Home, 7 Fashion Street, London, UK

1996

The Making of Scrapheap Services, Waddington Galleries, London, UK (Cat.)

Scrapheap Services, Electric Press Building, Leeds, UK, organised by the Henry Moore Institute; travelled to: Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

1995

Multiples: Editions from Scrapheap Services, Ridinghouse Editions, London, UK

Scrapheap Services, Tate Gallery, London, UK

1993

Warning Signs, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1992

Closing Down Sale, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1991

Appropriations 1-4, Karsten Schubert, London, UK (Cat.)

1990

Market, Building One, London, UK (Cat.)

Galerie Tanja Grunert, Cologne, Germany Studio Marconi, Milan, Italy

1989

Karsten Schubert, London, UK

Sovereign, Projects for the windows of the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York University, New York, USA

Public Collections

Arts Council of England

British Museum, London, UK

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Royal Academy, London, UK

Tate Collection, London, UK

The British Council, UK

The Government Art Collection, UK

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA