Mohammed Omer Khalil on his Art Journey,

travelling from Sudan to New York,

Print-Making, utilising Art to fight discrimination,

and Perspectives in History and the History of Art.

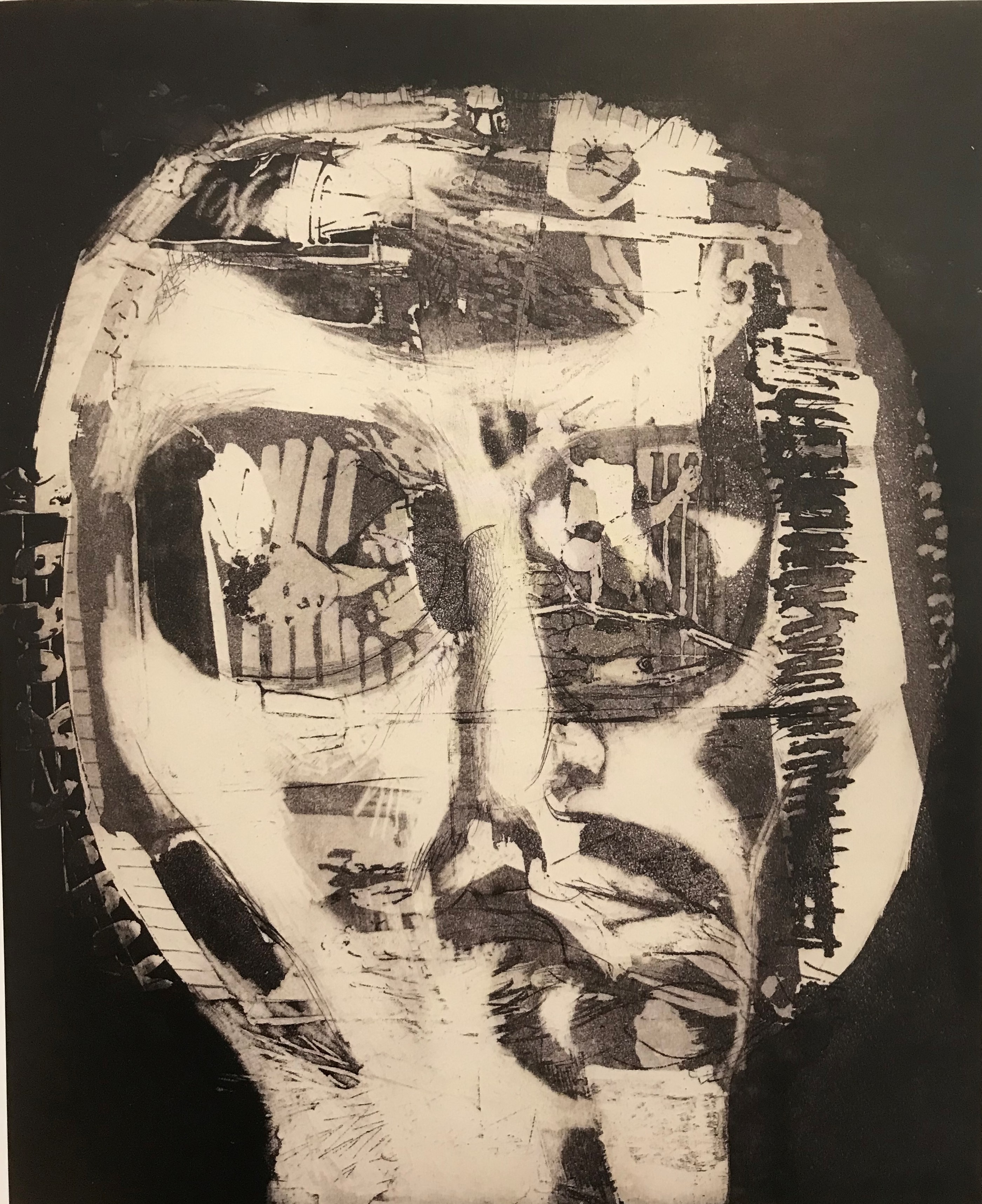

Head by Mohammed Omer Khalil at Aicon Gallery New York

Sudan is in the mist of heartbreaking turmoil, with hundreds having been killed or injured protesting for democracy and rights. On social media people have been turning their profile blue in solidarity with Sudan. The country, as Mohammed Omer Khalil references in an answer to one of the questions, is today seeking a new order.

Art as a tool speaks when humanity isn't allowed and the bravery of artists to create in difficult times is a testament to the power of creativity.

Artist Mohammed Omer Khalil comes from Sudan, in our interview with him he relays the influence the country has had on him throughout his life when living there and then in his life in New York, how his art has enabled him to fuse his culture with other cultures as well as ensure he is represented in the narrative.

What first interested you in art and can you share with us a little of your life journey from Sudan to USA?

In my last year of school, a man walked in to our classroom to inform us that they needed a third class of students for a new school that had opened. My passion at the time was to study architecture and not painting but they needed students for that. So regardless, myself and a friend of mine, Mokhtar Mohammed Ibrahim decided to join that third class. This was for the School of Fine and Applied Art, Khartoum. I stayed there for three years studying under English teachers, apart from the last year where I studied under Sudanese teachers, as Sudan had become independent in 1956. Following these years, I went to a teacher training school since they would immediately place you in a further education institution to earn a livelihood. After graduating from the teacher training school, I taught painting in that same school.

During that time, I also twice showed my work with the Association of Sudanese Artists. These shows were very successful and encouraged me to do more of my own work even though my primary income, though minuscule, came from teaching.

In 1963 I got a scholarship from the Sudanese government to go to Florence to study painting and fresco for 3 years at the Academia Di belle Arti. There I became a printmaker under Rudolfo Margheri but then returned to Sudan to comply obligations to the government and became the head of the department of painting at the Khartoum School. After a year, I quit and left Sudan even though my contract was for two years. I had married a colleague who is American and an artist Claire Anne Vignaux - Khalil and we left because she was pregnant and I was not earning enough to support a family. We came to New York and lived in Queens. It was difficult for me to get a job in New Yorkk, so I did odd jobs like printing silk screens, working on car speedometers, Television and radio panels and so on. But all these odd jobs were too toxic for me to continue and so after ten months, I quit and became a carpenter like my father who was an excellent carpenter back home in Burri. I helped Michael Kning a printmaker who printed lithographs for other artists and by the end of the year I joined Bob Blackburn, whom I met the first time I visited America, and printed etchings at his studio for other artists. On the side I did some of my own work to sustain myself to not go crazy.

Still Life by Mohammed Omer Khalil. 1963

Homage to Paulo Uccello by Mohammed Omer Khalil. 1966

How has printmaking impacted your art?

Doing etchings made me understand a lot about painting. Because in printmaking you scrape and burnish and start again to do others things and I applied that to painting which I had never done before.

The influence of pop art mixed with more traditional elements of pattern from Sudan take form in your paintings, how and when did you notice your interest in fusing both of those elements in your artworks?

I noticed it when I first came to the United Sates in 1964. At the World Fair in New York, I encountered the Kodak pavilion which had changing photographs on a big screen. I noticed that the screen was like my head filled with pictures and thus it made me envision an etching where I made a self-portrait with the Kodak pavilion as my head. That is the beginning of putting such elements into my work.

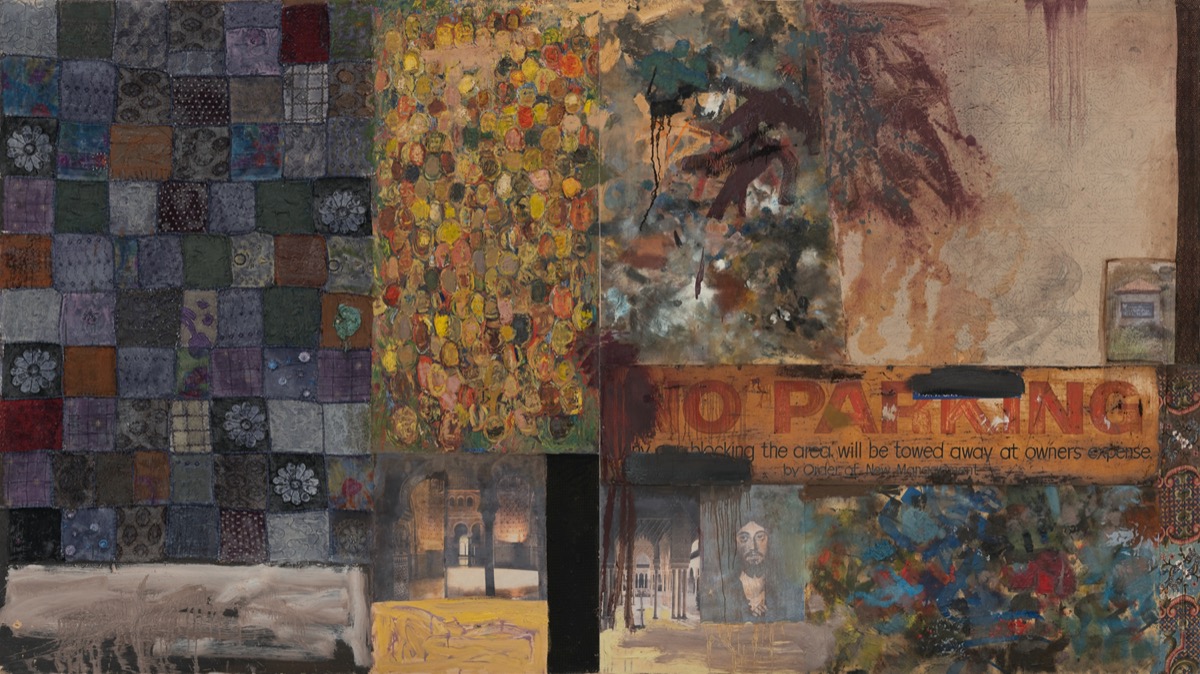

In your paintings you have used the words “to Love” or “No Parking, blocking the area will be towed away at owner’s expense”, do you use words in your work as metaphors?

Yes I do use words as metaphors for being shunned, not accepted as an artist for my colour or race. From the advertisement in America ' You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levey Real Jewish Rye Bread', I used that for my work as ' To Love , to Be, or To be an Artist you don’t have to BE! . The words 'No Parking' because after 800 years of Spain being ruled by the Moors, they were told by Crusaders that there was no space for them there and were sent back home.

The Moor's Last Sigh by Mohammed Omer Khalil

You Don't Have to Be I by Mohammed Omer Khalil. Oil and collage on canvas. 2003

You Don't Have to Be II by Mohammed Omer Khalil. Oil and collage on canvas. 2003

You also bring together different materials in your artworks, such as found objects, archival materials, textiles, photographs, what does that process of fusion enable you to convey?

I love to recycle things and give them a new life. A lot of my artwork materials have been picked up from the streets. When I use a found object, it stops being the object itself, it becomes part of the full artwork and turns into a new element. When Picasso used a newspaper to portray a violin or a cup or guitar, it stopped being a newspaper, you don’t think of it any longer as that, rather you think of the newspaper as a cup or a guitar.

Do you think of art as a dialogue between different cultures or that it can be?

Yes. I mean, if people accept your work in different places it opens minds, eyes and many things. My exhibition opening at the Aicon Gallery in New York was tremendous, so many people came from all over and the response was amazing without me being pigeonholed. I also just flew back from an opening in Casablanca, for the exhibition on African art: Morocco 'Prete- moi ton rêve !' or 'Lend me your dream!' . It is a travelling exhibition to Addis Ababa, Cape town, Dakar, Abidjan and Lagos. It is very odd that I am the only Sudanese artist in a major exhibition of African Art. It is my role to connect and communicate a dialogue.

You’ve taught at the Parsons School of Design, what has teaching meant to you and what advice would you give to the next generation of artists?

I tell students to work, work, work, and read. Children from the same art school as me do not always know of artists and what work has been done. I ask them to go read and see what has been done. If you do not have a past then you don’t have a future.

Art can bring into the conversation or into the History of Art, different perspectives and narratives, can you share with us your thoughts on how art can be a tool to do so?

I am scripting the History of Art through each painting, it is the job of critics and writers of this history to record it. My paintings discuss an important departure in history which is the fall of Andalusia. A significant time that influences the rest of history immensely. I am Sudanese and Sudan is the most important juncture of history in Africa and the world today. Sudan was also Christian before the Arabs; it was colonized by the British and now we are seeking a new order.

Alhamra (Granada) by Mohammad Omer Khalil. Oil and collage on wood. 2010-2011

How much power do you think art holds and can art change things for the better?

It can immensely change communities and lives in diffferent ways. After the Nazis did their horrible show on decadent art, art for many became a healing potion. And take for instance what happened in the small fishing village on the Atlantic coast of Morocco called Asilah; before art's impact on the village, it was in total ruin and abandoned and not even shown on the map. People had fled to Tangiers and elsewhere for work, but by 1978 it became one of the most important towns in Morocco. We began the printmaking workshop there in 1978 and the Festival of Art -Moussem, I have lived there since then and have noticed the change gradually each year.

Mohammed Omer Khalil studied at the School of Fine and Applied Art in Khartoum, Sudan and then pursued graduated studies in fresco painting and print-making in Florence. Since then, he has been living in the United States and until recently, taught at the Parsons School of Design in the New School. His work has been part of numerous solo and group exhibitions in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Asia and the Americas. His work is found in different public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, Sharjah Art Foundation, Grenoble Museum in France, the Jordanian National Museum and the Brooklyn Museum of Art. recently he was part of 'The Multiplication of Perspective’ a seminar at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 28, April 2019 to mark the 10th year of the MoMA's research program to address the dis-inclusions from art history practices of artists who have been present in the environs of the museum in New York.

Pomegranate by Mohammad Omer Khalil. Oil, acrylic and enamel on canvas. 1971