Interview with Dijon Dajee Hierlehy on Nobody’s Listening, the Yazidi Community,

the Power of Art and Virtual Reality Merging

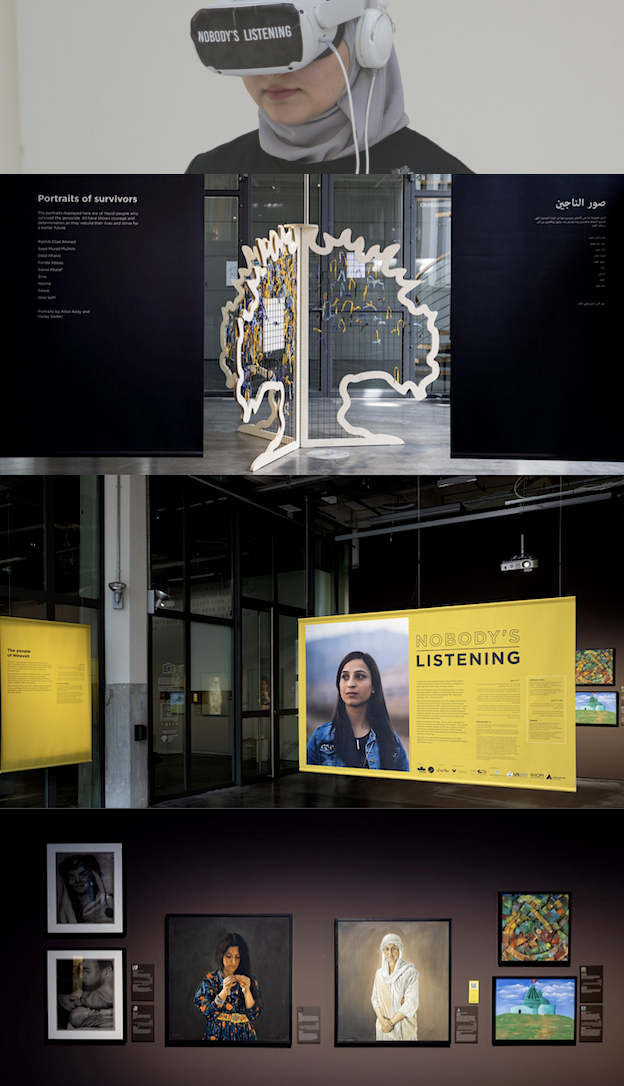

From top, Nobody's Listening Virtual Reality: "Nobody’s Listening: The Forgotten Voices of Sinjar", Photo credit: IOM Iraq/Yad Abdulqader, 2021; Three Stills of Art Exhibition by Nobody's Listening, Art in picture by Juliet Hassan, Jamil Soro, Thabit Mikhail

The Power of art is such that it can document, relay people's lived experiences, bring out a myriad of expressions, showcase perspectives, generate empathy, prompting understanding, breaking down perceptions.

Nobody’s Listening is a Virtual Reality (VR) experience and exhibition. It amplifies voices of survivors from the Yazidi community through the tool of art and technology, both merged as the VR—"Nobody’s Listening: The Forgotten Voices of Sinjar"—a virtual experience and an immersive sense of artworks, and through an art exhibition.

The VR shares storylines formed from several interviews with survivors, with technology as a tool utilised to create greater understanding through an immersive feeling and to educate, and the exhibition is made up of artworks by Yazidi artists and other communities.

Founded and curated by exhibition director Ryan D’Souza and art director Dijon Dajee Hierlehy MA, Nobody’s Listening, a touring exhibition, is co-organized with Yazda and Upstream XR, working closely with psychologists, in collaboration with the Society for Threatened People e.V. and the Institute for Transcultural Health Science at the Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University, designed and produced by Easy Tiger Creative Ltd.

The Nobody’s Listening VR experience premiered in 2020 at the Iraqi Parliament, and the immersive exhibition was first shown in 2021 at the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany. Since then, the exhibition in Iraq reached communities in Baghdad, Sulaimani, Kirkuk, Karbala, Dohuk, Sinjar, Mosul and beyond. The VR experience and art exhibition have been presented at the French Senate, German Bundestag, Luxembourg Parliament, U.S. Congress, and UK Parliament. The exhibition has toured institutions such as the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO), and the Representation of the State of Baden-Württemberg to the European Union in Brussels; and is currently on display at the University of Connecticut (UConn) and the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) in Washington, D.C. Satellite exhibitions have been hosted at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, in Africa at events organised by the Nobel Laureate Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation, at universities, including Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, Yale, Columbia, Georgetown, and King’s College London, University College London (UCL). Nobody's Listening has also been presented at high schools in the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The background to Nobody’s Listening derives from the heartbreaking events that occurred in 2014 in the Sinjar district in Northern Iraq, home to the Yazidi community. Devastating reports of kidnapping and enslavement filled the news with distressing scenes of people trying to flee to safety. Nobody’s Listening puts back at the forefront of the international stage the ordeal subjected onto communities, with the platform working towards change for the Yazidi community and other communities, generating greater awareness, and opening up conversations.

Working closely with the civil society organisation Yazda, Nobody’s Listening’s platform relays that from 2019, over 2800 Yazidi women and children remain missing, thousands are displaced and continue to live in camps, and many have resettled abroad. The numbers of the missing change, depending on rescue missions.

Nobody’s Listening explores the consequences on communities, the devastation on their lives and their cultural heritage, via Virtual Reality technology,—which acts as a tool to inform, propel empathy and render the participant to feel and view the surroundings of the survivors, given a choice of different pathways to experience,—and through art and photography by Yazidi artists and other communities affected—Assyrians, Christians, Kaka’i, Sabean Mandaeans, Shabak, Turkmen and Arab Shi’a.

It provides a space for survivors' voices to be expressed, their stories shared, their plight recognised, and their hopes listened to. With Nobody’s Listening inviting those on social media to pledge #WeAreListening.

Artworks part of Nobody’s Listening are moving and powerful, sharing testimonials and lived experiences, the impact of the art filled with deep expression and artistic talent. The painful emotions the artists have experienced are felt across their art, leaving the viewer in awe of the survivors' courage.

Nobody’s Listening has been able to produce a pivotal communicative tool in technology and art, an important exhibition, motivating all to confront and try to understand what was subjected onto the communities, the trauma and feelings.

We spoke to co-founder and art director Dijon Dajee Hierlehy MA on the roots of Nobody’s Listening, what it entails, the VR headset, the exhibition, the artists, the continuous work the platform is doing, helping the Yazidis and the other affected communities, and what the VR and art is propelling, as we dive deeper into the project’s effects, how it stemmed and developed.

Can you tell us about Nobody’s Listening, the background to the project, why and how it came about?

Ryan and I have been friends for a number of years, (Ryan D’Souza co-founder and exhibition director of Nobody’s Listening), he had left the UK to work with the United Nations in Somalia, New York and other places around the world, but upon his return, feeling frustrated with work not going beyond written reports, he wanted to start something that did.

He’d met Nadia Murad who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize, was really moved by her and wanted to help do something for the Yazidi community who he felt were being lost to history. As the 5th anniversary of the genocide approached, Ryan thought something needed to be done to reinvigorate this cause and create more of an emotional link.

He approached me in 2019 with the idea of using Virtual Reality (VR) to showcase what the Yazidis were going through. There were lots of positives to using Virtual Reality, because it gives people an impression they are on the ground rather than feeling removed from the situation.

I thought along with that, as the community is very artistic, it would be good if we were able to show some of their artworks create an exhibition to integrate with the Virtual Reality. For those living in camps in the north of Iraq there's not much to do all day, they create works of art, a testimony to what they've endured, when workers or peacekeepers come to see them, they are able to sell them their artworks.

We set off trying to create this art and technology project, and started filming for the VR in 2019, with a soft launch in 2020 in Baghdad which went really well, but then Covid happened which obviously held us up.

However, we used that time to define our project and make it even better. In 2021 we exhibited in Karlsruhe, Germany and were supported by State Ministry of Baden Wurttemberg in Germany. Since then, Nobody’s Listening has toured the world, including a collaboration with Somerset House, the Courtauld Institute and the FCDO the Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office in the UK, to put an exhibition on at the Foreign Office.

The background to all of this, we can for our discussion, mention when the Syrian Civil War erupted, it led to lots of little different factions breaking out. The group ISIS, Isil or Daesh as they are sometimes called, came up from Syria which is to the west of Iraq into the northern part of Iraq in 2014.

The border between Iraq and Syria is an area called Nineveh where the Yazidis live or lived mostly—now many are either in camps in Kurdistan or in the diaspora,—in this area is a place called Sinjar, and directly in the center is Sinjar Mountain, where the Yazidis fled up to when they came under attack. The UN Human Rights Council constituted the attacks as a genocide. At some point, a safe passage into North Kurdistan area and into Turkey was sort of established.

The Yazidis are a minority community that have been persecuted, they say that historically there have been about 72 persecutions, and every single time they’ve sought safety on the Sinjar mountain which has saved them, and so they feel it’s a safe haven of theirs.

One of our exhibiting photographers, Zmnako Ismael, was on that mountain at that time when the attack on the Yazidi community took place. He’s a great person who just wanted the stories he was picturing to be shared as widely as possible, and was really helpful getting that story across.

Girl on Sinjar Mountain by Zmnako Ismael

Can you walk us through and tell us a little bit what we’d experience if we were to put the VR headset on?

When you put on the headset, it’s an educational experience. It’s structured and aimed to educate about the Yazidi community, what happened to them and how they are living now. The VR was created with that direction and intention, and we’ve shared the VR experience with schools.

There’s nothing graphic, but of course if a person has been affected by sexual violence or genocide or any of the themes involved, we do warn that it could be triggering.

For the VR we pieced together various interviews, we didn’t want it to stem from one person’s trajectory as that would have been too heavy on that one person and we wanted it to be more of a representative story of people at that time. So we formed a storyline from the various interviews and worked very closely with the organisation Yazda as well as with psychologists.

The VR provides the topographic location of Sinjar and options to experience different paths, choosing between a young girl, boy, relaying each of their story and perspective, or the path of a fighter, as we wanted to also show the motivation behind how people came to that.

Through the headset you can virtually enter a Yazidi temple, walk around the area, visit a school in Sinjar, go into a home of a survivor, see how they were living at the time, and what happened to them. You can also choose to go see people in camps and how they're living now and be exposed to what they would call for if they were able to speak directly one on one with the person experiencing the virtual reality.

You mentioned that you worked closely with the organisation Yazda, can you share with us about them?

Do they help provide art materials?

They are a Yazidi organisation set up after the genocide to lobby for their community, trying to summon government interest. They are on the ground helping and supporting the Yazidi communities still in Iraq, but also those in the diaspora—in America, the UK and Germany.

Yes absolutely Yazda do help with providing art materials. There are many different organizations trying to do things but it is hard if you're not on a governmental level.

How was it merging art with technology?

The way in which we've done it, is that between the sceneries within the VR, you can walk through a painting—giving access to the next scenery.

Because it's immersive, you can't look at your phone, you can't do anything else while you're partaking in the VR, it really takes you into someone else's world. There’s no need to connect to a wi-fi, and no remote control necessary, with our VR, we have designed it so you walk through places physically.

The paintings are also shown in the real world in an exhibition, so that combination of linking together the virtual and the real world really works well in terms of bringing different experiences and perspectives.

What were some of the reactions of people who experienced the VR? Have you received feedback?

We carried out impact assessment reports, took the VR to universities, educating people about the Yazidi community, helping to overcome any prejudice.

There was an initial study done with The Polytechnic University of Sulaimani, and we will probably go back after five years to see the effect it had and how it has helped in any way. These types of projects are very hard to assess, most projects are, unless in financial monetary terms.

One of the most impressive things we noticed, was when showcasing Nobody’s Listening to the members of the Iraqi Parliament. At that time, each community had a pre-existing impression of each other, some politicians would have probably thought or said that the Yazidis, they should pull themselves up, build themselves and so forth, that was the kind of impression that they had on the community.

But then through the VR, another impression set in, people started to really feel what the Yazidi community had experienced and how there were no possibilities for them to pull themselves up by that construct. It was a real game changer for most politicians who viewed Nobody’s Listening.

One of the survivors came with us and explained that something had to be done for the Yazidis, and in 2021, the Iraqi Council of Representatives approved a Yazidi Survivors Law, which meant reparations for the survivors and recognition of a genocide towards the Yazidis as well as on Christian, Shabak, and Turkmen communities.

The paintings and photographs are very moving and powerful, what was your approach to your curation?

We were introduced to the artists through Yazda. They reached out to the community asking if anyone practiced art and if they wanted to participate in our project.

And then from the number of names we received we set out to structure the exhibition. We had a basic idea in our minds of how that would be, we wanted the artworks to relay the survivors stories, explaining who they are, what happened to them and then the outcome of that.

We were also conscious that there were many communities such as Christians, Assyrians, Kaka’i, Sabean Mandaeans, Shabak, Turkmen and Arab Shi’a targeted or affected at that time, and we wanted to make sure the exhibition was representative of all of them as well, so we selected paintings from diverse communities showcasing their stories. We also reached out to a number of photographers.

Thikran & Mother by Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum

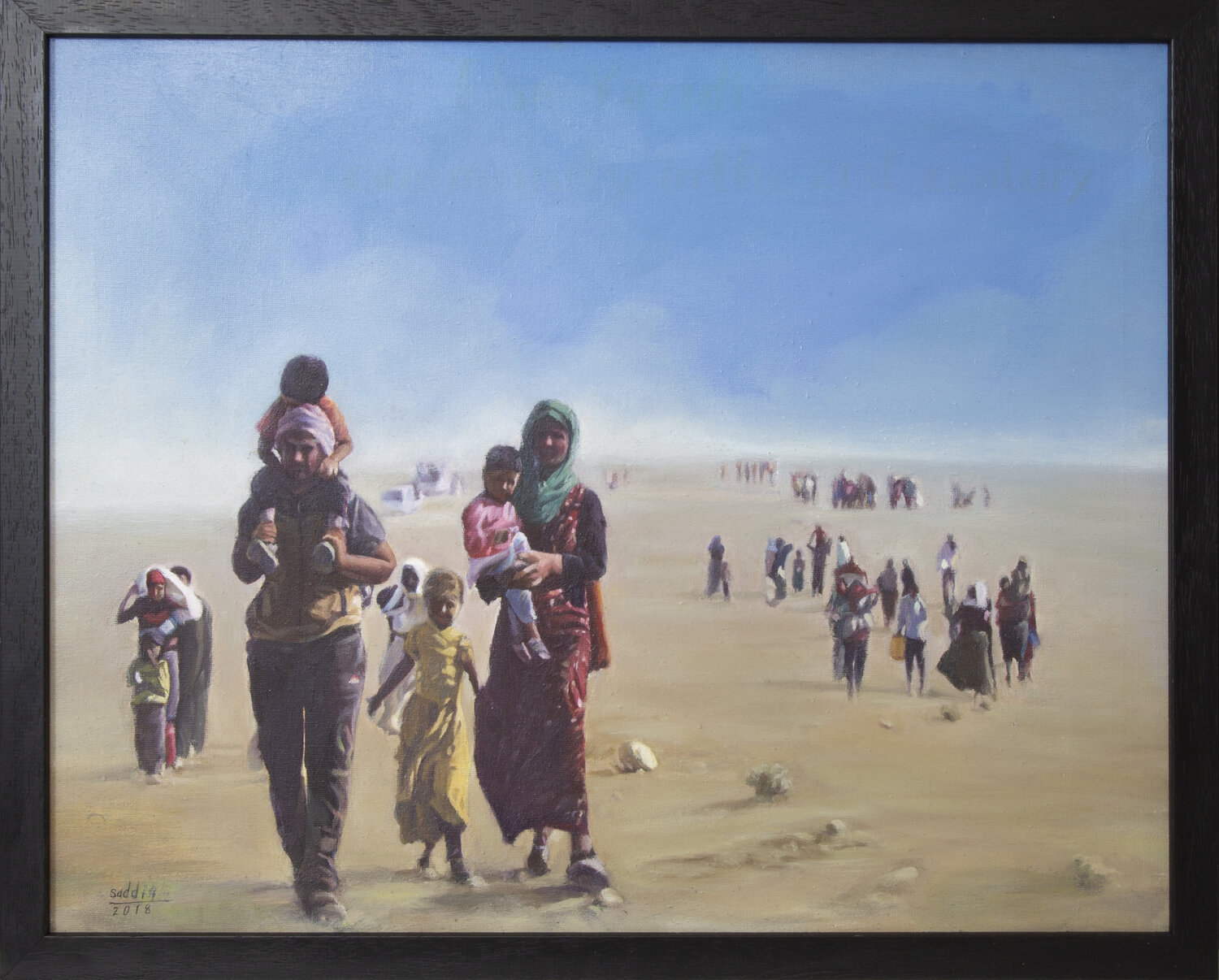

Fleeing from Death by Sadiq Khedar (b.1995), Oil on Canvas

" Sadiq’s painting Fleeing from Death documents the most dramatic event of his life. The work depicts Yazidi families, with young children among them, on Mount Sinjar in the wake of the devastating attack on their communities. [...]

Sadiq himself spent one week on the mountain and explains that he painted this picture in response to his sadness at seeing so many people, young and old, fleeing from danger without food, water, or even shoes. He painted what he saw with his own eyes, in order not to forget. [...]

He is passionate about the role of art in the documentation of history and urges talented artists to continue developing their skills and to document events that they live through, just as he has done."—Nobody's Listening / Sadik Khedar: https://www.nobodys-listening.com/sadiq-khedar

The Darkness is covering me by Salam Noh

" [...] it was in Greece that Salam and his brothers had first found support for their artwork, when a volunteer in the camp brought them the materials to begin painting with acrylics and oil. By October 2016 Salam’s brother Ismail had his first seven paintings exhibited in Vienna, Austria, and Salam then had his own works exhibited in Zurich, Switzerland, in early 2017. Salam, Ismail, and their brother Jason now run the website Brotherly Art, displaying all their artworks online and at exhibitions worldwide, and donating a share of their profits to refugees and displaced people in need. For his painting “The Darkness is Covering Me” Salam collaborated with his brother Sahir, who wrote an accompanying poem.

The Darkness Is Covering Me Poem by Sahir Noh

The darkness is covering me like a blanket...

Alone sitting in this room,

So dark.

So alone.

Crying my heart out

While waiting,

Waiting for your return...

Waiting for the light in our eyes shall brighten the sky again...

Waiting for the lights to go out and the day turns into night.

Still I’m waiting for a touch from your hands to keep me alive...

There I’m sitting near the window

Looking for a shadow

Or to another shooting star

So I can make a wish once more...

Which is to hug you once more.

Asked why he thinks it is important to have artists within the Yazidi community, Salam responds: “To keep the message and story alive, to keep reminding people the genocide is happening even if the media doesn’t pay attention, and to generate powerful emotions and empathy through painting Yazidi stories.” "—Salam Noh—Nobody's Listening /Salam Noh https://www.nobodys-listening.com/salam-noh

Untitled, painting by Suhalia Dakhil Talo (b. 2000), Oil on Canvas

" Suhalia is now twenty years old and has continued to make art to remember what she endured. Her drawings allow her to bring back the memories of the people she has lost in her life. Her untitled painting of a silenced Yazidi girl is based on the many she was imprisoned with who were beaten and tortured. [...] Suhalia wants to use her work to spread a message about what happened to her, and what more needs to be done. " —Nobody's Listening /Suhalia Dakhil Talo https://www.nobodys-listening.com/suhalia-dakhil-talo

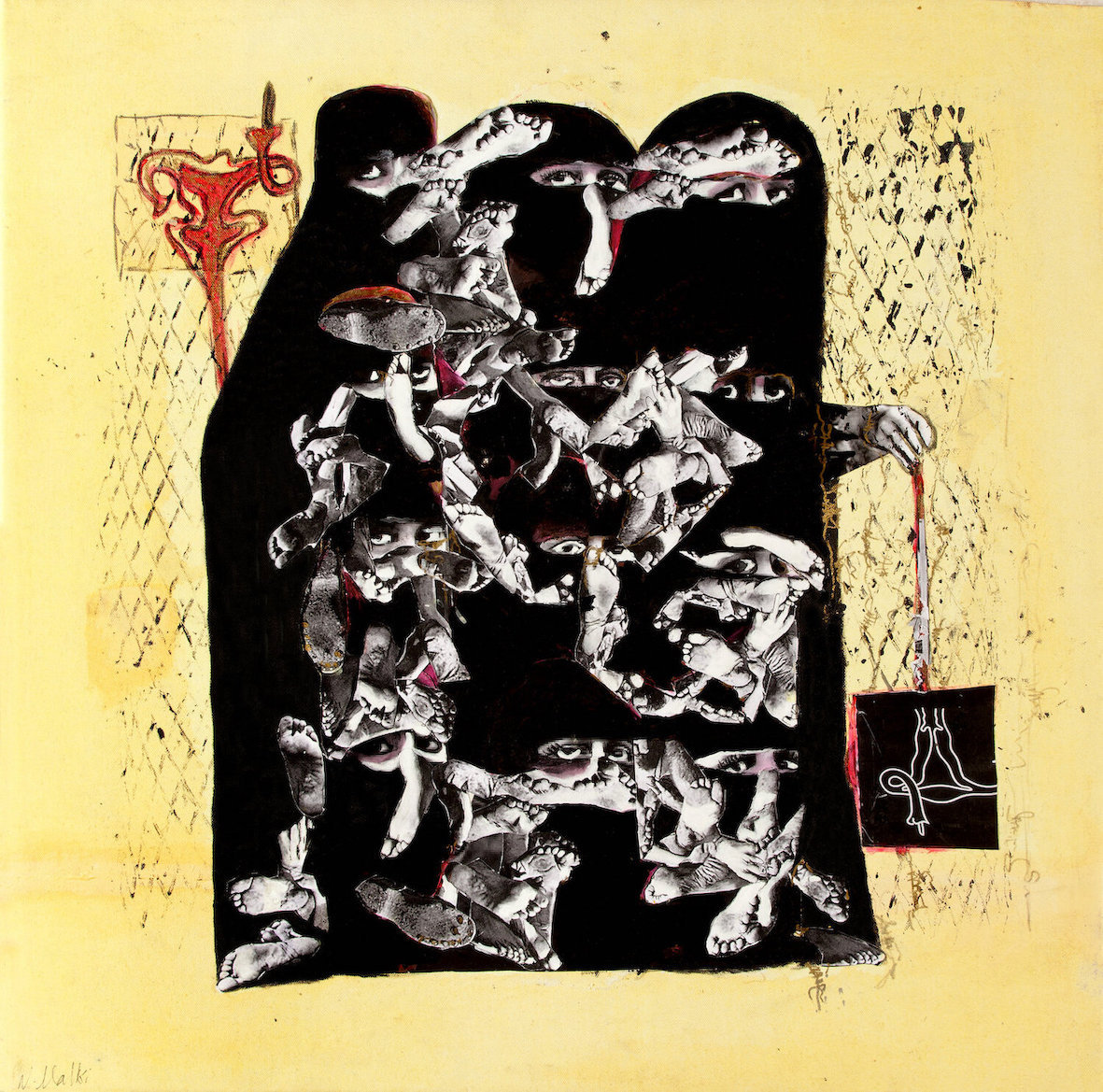

The Screaming Womb by Nahrin Malki, Mixed media on canvas

"[...] the Assyrian plight in Iraq and Syria is similar to the Yazidi experience, with tens of thousands of people driven out of their ancestral lands. [...] Her main objective now is to connect the Assyrian people with their heritage and collective experience, through the central theme of suffering in her artwork. The Assyrian diaspora share collective memories of pain [...] . She explains that through her artwork and advocacy, she wants to help all persecuted minorities, and not just the Assyrians: “I want to talk about and represent other people who are being killed and brutalized. At the end of the day I am also human, and we are all brothers and sisters in humanity. As an Assyrian I can feel the pain of other people around the world who are suffering."—Nahrin Malki—Nobody's Listening /Nahrin Malki https://www.nobodys-listening.com/nahrin-malki

.jpg)

Peace (2019) by Juliet Hassan (b.1997), Charcoal on paper

" Among large crowds of Yazidis fleeing their villages and ascending the mountain, the cars broke down and Juliet and her family had to continue on foot, leaving food and water supplies behind. “My father was very sick,” she explains, “so we had to stay somewhere close by, not at the top of the mountain. We stayed in the same place for a week and received water and simple food from local farmers.” [...] Since living in the camp, she has worked with NGOs and produced some paintings to help people understand Yazidi history and culture: “Art is something very important in my life,” [...]

Above all she hopes for a society in which people of all backgrounds can live in peace, without racism and persecution. “I want the UN and international community to support those families who suffered a lot, and to encourage talented people to achieve their goals. ” – Juliet Hassan "—Nobody's Listening /Juliet Hassan https://www.nobodys-listening.com/juliet-hassan

Art can be a great healer, a powerful tool to share lived experiences and express oneself.

You mentioned when we were talking about the VR that it might be triggering if trauma has previously been experienced, but that there was care taken to ensure nothing graphic is shown.

How did you approach not to activate any re-traumatization, the choices of visual paintings and photographs? And what are your thoughts on art and technology as powerful tools?

In creating Nobody's Listening, it was important for us to be working on it in a controlled but compassionate way, and so we consulted a number of psychologists all the way through, heavily relying on Dr. Sarah Whittaker and Dr. Jan Kizilhan throughout the process.

Some of the artworks are heavy, because the situation is. There are a few abstract works that put across the point but don’t do it in a direct way.

We didn’t want to cover up the reality of what was happening, we had to share the survivor’s truth, what people went through—their testimonies.

We do however tailor the exhibition depending on the institutions that we're showing or presenting at; for instance if it’s a school we are mindful of what is on display. Last year we visited about 20 schools in the UK. Young children have grown up with technology, so placing a VR headset on them, you get a sense of how at ease they are with the workings of technology, the possibilities of where it can go, that technology can be a useful tool in which to move towards.

There’s also a difference between viewing the artworks when they are in an exhibition hanging on a wall with an information panel by it, the website showcasing the artworks with the survivors own stories and testimonies in greater detail, and going through the VR where you feel everything, and where there’s also a second step, a QR code that you can eventually dial in to go to the website to see those fuller length stories of the art, going deeper into what happened.

An important part of this project which I didn't realise to begin with, especially in terms of the psychology, is that at conferences, at delegations of violence or genocide, often, if you are trying to represent a community, a survivor is there delivering a speech, and in that speech a small part of them is re-living their experience, re-traumatising, and every single time they deliver a speech, they are going through their experience, their trauma all over again and again.

They either become null to it, or it just becomes too heavy for them and they can't do it anymore. So this school of using the Virtuality Reality, means that a survivor can just tell their story that one time and it can be experienced and shared as many times as needed, viewers can empathise with a story in a much more direct way without the survivor being re-traumatised.

Untitled, painting by Ivana Waleed (b.1996), Acrylic on paper

" Ivana is a young Yazidi artist from the village of Tel Qasab, near Sinjar in northern Iraq. She endured many months of brutality and suffering [...] Ivana remembers a simple but happy village life with her parents and many siblings before the genocide of the Yazidi community[...]

"[...] I wanted to be a doctor – I wanted to be a role model to other women.” Now living as a refugee in Germany, her ambition to work as a doctor remains. One of the support initiatives of the BadenWürttemberg project is art therapy, where participants draw and then discuss their artworks and related emotions. Ivana’s untitled painting of a faceless woman was the product of just two such meetings in 2019. She reveals that she had wanted to draw a face for this woman, but ultimately felt unable: “When I stand in front of this picture, I think it is me, and when other women stand in front of it they should think the same, because this woman represents every one of us. If she had a face it would determine whether she is sad or happy, but nobody could be sure; each woman who looks at the painting should make her own decision as to what she sees and what name the painting should have.” "– Ivana Waleed —Nobody's Listening /Ivana Waleed https://www.nobodys-listening.com/ivana-waleed

When I was reading the stories of all the artists and looking through their artworks, alongside wanting to relay their stories, many also speak of and seek justice, and are continuing to create art.

Justice I think is important because it creates accountability.

As far as I know three members of ISIS have actually been prosecuted directly for what happened and the Iraqi Council of Representatives approved a Yazidi Survivors Law in 2021.

There are still many Yazidis in captivity. Every now and again some Yazidis are released, but many of them have been indoctrinated, but we don't really know, it depends on each individual case.

Alongside their art, those that have fled to Germany, the US or the UK, have thankfully been able to find jobs.

The survivors that are living in the camps, in practical terms there's very little to do, so they will most likely continue to make artworks and hope to get their cause out there.

Wishes by Jamil Soro (b.1972), Oil on Canvas

"From an early age he has wanted to depict Yazidi culture and suffering, and to show the world what it means to be a Yazidi. [...] Observing the events of 2014 from Germany, he felt helpless: “It is impossible to describe how much pain I felt; it was impossible for us to do anything,” he says.

[...]The principal message that Jamil wants to convey with his work relates to the theme of shared humanity [...]“They should see that we are also humans, and we want to be treated as humans. We all have eyes and noses; we are all human.” "– Jamil Soro – Nobody's Listening / Jamil Soro https://www.nobodys-listening.com/jamil-soro

You have a Masters of Philosophy, did aspects of philosophy come in at some point during your process of curation?

Not in a direct way, but perhaps in the background. I've always been into philosophy of art and into aesthetics.

I have an idea about art that’s maybe not a conventional one, which is that it can sort of be a social mobility programme. Like redistributing wealth, or elevating stories up, I guess that’s what art can do. Sports, football does that too. It’s taking people who have a skill and elevating them out. So I hope that this exhibition, Nobody’s Listening, is kind of a way of achieving that, amplifying and elevating stories, sharing them to reach as many people as it can.

In regards to what you are doing with highlighting protection of cultural heritage, can you tell us more about that?

Cultural heritage is a part of the idea of genocide, which is to demolish the community’s artefacts, to destroy any trace of who people are.

An English artist we have worked with, Piers Secunda went out to Iraq and did mouldings of temples and reliefs that he then was able to preserve. Mosques, Churches, Shrines, Temples, artefacts and historical sites, representing diverse religious groups were destroyed in the city Nineveh. There is a section on our website highlighting a 3D model of a destroyed Yazidi temple made available by Forensic Architecture, and reliefs of Assyrian monuments from the Museum of Mosul provided by Piers Secunda.

We are hoping through our project to safeguard culture, protect customs, to keep that all alive. The thought that people’s customs can just get lost within our lifetime is I believe, really sad.

That in some way, we’re helping to preserve cultural heritage is an important part of Nobody’s Listening.

If anyone wants to help the artists, to donate to the project, it is through the website?

Yes there is a donate button on the website which all goes directly to the Yazda organisation.

If people wanted to contact us about helping a specific artist directly, we could try to set that up.

We don’t make any money from the donations there, to keep the project Nobody’s Listening going to the next stage we talk to delegations to raise funds for that.

See https://www.nobodys-listening.com

Link to all the featured artists in Nobody's Listening: https://www.nobodys-listening.com/exhibition

Yazidi Girl by Falah Al-Rasam, Oil on canvas

" Falah is a Yazidi artist currently living in an IDP camp in Iraqi Kurdistan. [...] Falah’s literary background and experience in writing poetry and short stories inspires his art. He has read widely from French, English, and Arabic literature, and he is inspired by religious and philosophical works and authors such as Kahlil Gibran: “They taught me to understand life in a philosophical way, to understand life more”, says Falah. He now wants to deliver a message to the world through his artwork: “I have a strong desire to do something positive. Sometimes I look at the paintings and feel very happy that I have done that.”

[...] untitled painting shows a young Yazidi girl in an IDP camp. Falah took photographs of her in 2019, just after she had been released following four years in captivity with her mother and siblings, and with her father still missing. In this work he has focused on the child’s innocent but emotional expression, hoping to convey to the world the stark reality of what has happened to such victims.

Above all, Falah wants to secure the right for his people to live peacefully: “We want other nations and religions to live in peace and we want others to do that for us.” "– Falah Al-Rasam – Nobody's Listening / Falah Al-Rasam https://www.nobodys-listening.com/falah-alrasam

Dijon Dajee Hierlehy MA Art Director and Co-Founder of Nobody's Listening

Dijon Dajee-Hierlehy has been working as an artist and curator for the past 14 years. He has exhibited internationally including at the Royal College of Art, Central Saint Martins and Miami Art Basel. He was a resident artist at Lights of Soho where he was exhibited alongside Tracy Emin and Chris Levine.

He has curated exhibitions and designed events for a number of high profile clients including, Cartier, Aspinals of London, TEDx, Gleneagles Hotel, Lisson Gallery and HRH Prince of Wales.

"Nobody’s Listening: The Forgotten Voices of Sinjar" is co-organized with Yazda and Upstream XR. The project received support and collaboration from institutions, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations, and Google Arts & Culture.

Upstream XR have also produced VR | 360° Immersive films on Ukraine and Tigray. "Remember Tigray VR | A 360° Immersive Testimony of Genocide, Survival & Resilience" was first premiered in 2023, and is now available to view online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=wrLTRZNq-R0

"Remember Tigray VR is the first immersive documentary to capture the atrocities in Tigray using a 360-degree camera transported into the region in February 2023. Filmed by Ethiopian cinematographers Tedros Gebreabzgi and Fetsum B. Woldearegay, the project presents powerful scenes that unveil the aftermath of the conflict. The script, written by Dr. Charlotte Touati and Meareg Tewolde, centers on Mahlet, a Tigrayan survivor of sexual violence, showcasing her profound story of trauma and resilience. Co-created by Matthew Niederhauser, John Fitzgerald, and Ryan D'Souza, the film serves as a call to action, highlighting the urgent need for justice and accountability for the Tigray genocide and support for all survivors of sexual violence in Ethiopia."

Ryan D'Souza Exhibition Director / Founder of Nobody's Listening

Ryan Xavier D'Souza has been working on human rights advocacy and genocide prevention for the past 10 years. He has worked for the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da'esh/ISIL, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia, and was a visiting fellow with the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. He previously served as a consultant for the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide.

Before joining the United Nations peace operation in Somalia, he led advocacy and policy at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, a New York-based human rights organization. During this time, he supported efforts by Yazda, Nadia Murad, and Amal Clooney to mobilize the UN Security Council to hold ISIS accountable for the genocide in northern Iraq.

Pictures courtesy and copyright of Nobody's Listening and all artists