Professor Geoffrey Batchen on

The History of Photography, Adding to its Canon and

the Layers of Meanings and Impacts Photography Holds

From walls to monuments, paintings to photographs, in objects and memento’s, we are all draped in art history.

Art history provides an insight onto understanding our world and our surroundings.

Professor Geoffrey Batchen’s profound knowledge and writings on art history, on the history of photography, his books such as 'Negative/Positive: A History of Photography’, curating exhibitions and his teachings, bring to light the history of photography to include all its creative genres, categories such as camera-less, vernacular photography and highlighting the negative. His work relays the histories of photography that may have either been excluded or overlooked, as well as delving into what photography signifies to our lives and for our future, uncovering the effects and impacts digital photography has on our climate.

Professor Batchen conveys photography’s relationship to memory, the conditions for photography's development, its essence, encouraging its layers to reveal a more complete understanding of photography and what it propels.

What is your first memory of photography, what ignited your interest in this art and drew you towards art history?

It is impossible to have a first memory of photography, as photographs are as ubiquitous as the air we breathe; they have always been there, surrounding me, whether I was aware of them or not. However, I do remember being given my first camera, an old one I inherited from an aged relative. It was a difficult instrument to use and all my attempts resulted in blurred pictures. Eventually I received a new Kodak Instamatic camera as a gift and began making colour snapshots, just like everyone else. However, I didn’t take any particular interest in photography as an art form, or even as a cultural phenomenon, until the 1980s. I was never taught anything about it in Australia during my first two degrees (in architecture and art history). But when I was lucky enough to get into the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program in New York in 1983, I encountered the advent of postmodernism and a cultural scene in which photography was a dominant component. Artists like Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman and critics like Craig Owens and Martha Rosler saw photographic images as objects worthy of close analysis, as if they embodied the values of modernism itself. I became interested in the possibility of writing a PhD thesis about the death of photography (an issue made all the more acute by the introduction of digital media in the late 1980s). It seemed impossible to address such a question without also engaging with the history of photography’s origins. Thus began my study of photography and its various histories.

You curated the exhibition ‘Forget Me Not' on memory and photography, could you tell us about exploring the relationship between the two?

That exhibition came about by accident. In 2000 I gave a talk in Amsterdam about vernacular photography and was approached afterwards by a curator from the Van Gogh Museum and offered an opportunity to curate an exhibition about the same material. I decided to focus the exhibition on the relationship of photography and memory, featuring hybrid photographic objects that seemed to be trying to enhance their memorial capacities by adding touch, smell and even sound to their sensorial armory. Such objects included daguerreotype lockets that also enclosed a lock of hair or painted tintype portraits or a photograph of a warship that had visited Brazil and was decorated with colourful Brazilian butterfly wings. I suggested that these additions were necessary in order to overcome photography’s tendency to replace the personal, emotional pang of memory with the fixed documentation of history. In other words, I argued against the popular idea that photography is a ‘mirror with a memory’, instead stressing memory’s (and photography’s) creative and multi-sensory qualities. But it was also a chance to put on display a vast array of types of photograph that don’t normally get much attention in museums. The exhibition was also shown in Iceland, the UK and New York, and a variation on it was mounted in Japan. Each of those venues added material from their own cultural traditions, a reminder that memorial photography is simultaneously global and local.

Your work has covered the beginnings of photography, what were some of the conditions that helped this medium to emerge?

Photography emerged in Western Europe and its colonies with the advent of modernity, and it shares many of modern life’s own particular conditions of possibility. These include the Industrial Revolution and its scientific advances and demands, and the economic and political systems that motivated consumer capitalism and colonial conquest and trade. But it also includes revolutionary changes in understandings of time, space, subjectivity and representation, changes most overtly manifested in the Romantic movement. Photography could well be regarded as a technological response to the challenges that accompanied that movement, as an effort to somehow reconcile transience and fixity in a pictorial form. It therefore has much in common with, for example, the poetry of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the paintings of John Constable. But it also channels the ideology of positivism and the search for ways to record information with mechanical exactitude. The important thing to recognise is that there is no evidence of a desire to photograph before about 1800 and the emergence of these conditions. Photography is an entirely modern phenomenon.

You have written about the history of photography, seeking to add to its canon, to include vernacular photography, all types of categories, such as camera-less photography, and with that, bringing a global perspective. What have you found has been some of the histories, in terms of creative genres, moments in history, as well as many parts of the world, that rightfully belong within the history of photography but might have been marginalized or overlooked?

When I first began to study photography, I was also interested in the critical thinking of French philosophers like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. I therefore gravitated towards both big abstract questions, like ‘when (and why) did photography begin?’, and methods of doing history which complicated the political hierarchies invested in binary oppositions. I have increasingly sought to complicate the relationship between the centre and those entities considered to be at its margins. These entities are almost inevitably seen as secondary and of lesser value. This unequal relationship pertains as much to survey histories of photography, which suppress the existence of photographs produced in regional cultures (from Australia to Syria), as it does to studies that ignore or denigrate photographs important to women, or the backs of photographs, or the negative as a key component of photographic practice, or photographs made without cameras, or ordinary, hybrid or commercial photographs, and so on. There are particular reasons why each of these aspects of photography has been marginalized, but, in each case, we’re talking about a politics of othering (we’re talking, in other words, about the discursive reiteration of sexism, racism and colonialism). The negative, for example, has been derogatorily associated with the feminine and blackness ever since its invention and treated accordingly. We rarely see them reproduced in histories of photography or discussed as photographs in their own right. My work as a historian tries to disrupt the unconscious prejudices of my own discipline by consistently engaging those things which the discipline at large wants to push away from itself.

.jpg)

John Murray (England/India), Nagina Mosque, Agra Fort, India, 1857–60

waxed calotype paper negative with added pigment

36.8 x 45.9 cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Where for you does photojournalism sit in the realm of the history of photography?

My work has argued for a representative (rather than a comprehensive) history of photography and tried to identify and establish ways in which such a history could be articulated. Photojournalism is, of course, an important genre and practice and deserves a place within such histories. The question is, how should it be incorporated within this representative history? How can one present the specificities of photojournalism’s contributions to modern culture while also contesting the various prejudices that I have already mentioned? How can we talk about photojournalism while also addressing sexism, racism and colonialism? These are the challenges that lie ahead.

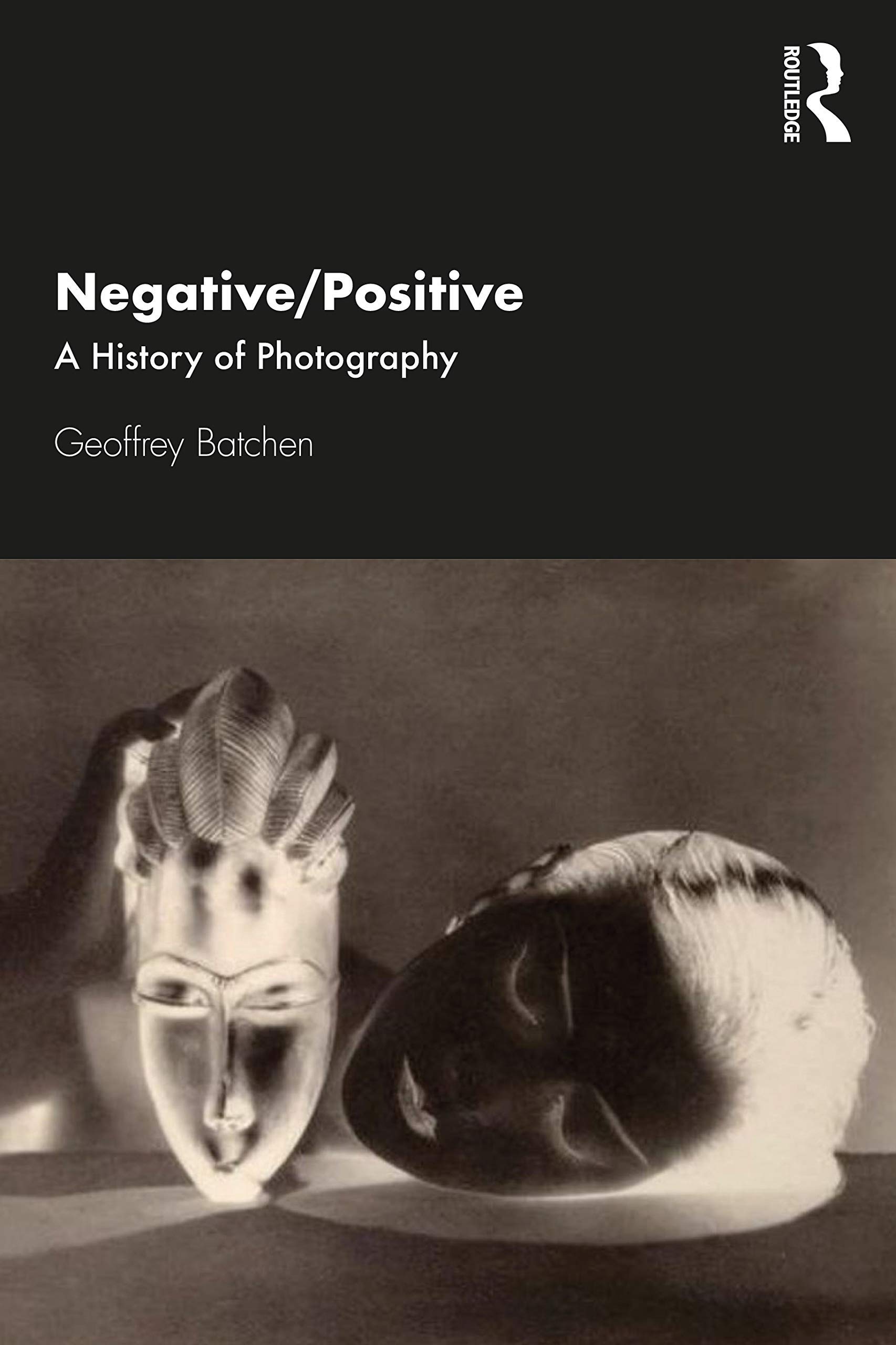

In your latest book ‘Negative/Positive A History of Photography’ you delve into the role of the negative, image reproduction, ownership, could you tell us about your book and on some of those points you looked into?

As I have explained above, the negative is one of those elements of photographic practice that tends to be ignored or denigrated in most accounts of the medium. It has traditionally been associated with the feminine or blackness and treated accordingly. My book attempts to provide a history of this treatment and with it a commentary on the crucial role that negatives have played within photographic practice. It therefore looks at some representative negatives (including daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes, processes which merge negative and positive attributes in a single image) but also at what paper and celluloid negatives do: they allow the production of multiple positive prints from a single matrix. And those prints can be enlarged or diminished in size or modified in appearance during the act of printing. In addition, it allows the same photographic image to be seen in many places at the same time. It makes it possible for one person to expose a negative and other people to print from it, thus introducing the activities of work and commerce into photography’s story. In other words, a history of the negative necessitates a reflection on the identity of the photograph but also a rumination on the effects of reproduction, repetition and dissemination (all aspects of photographic life that are again usually ignored by other historians). As I am speaking about a figure (‘the negative’), rather than being intent on isolating a few outstanding masterpieces, my history can include examples from all over the world, some of them made by known photographers but many of them not. By looking at what is usually regarded as a marginal element of photography, a whole new perspective on the medium is made possible.

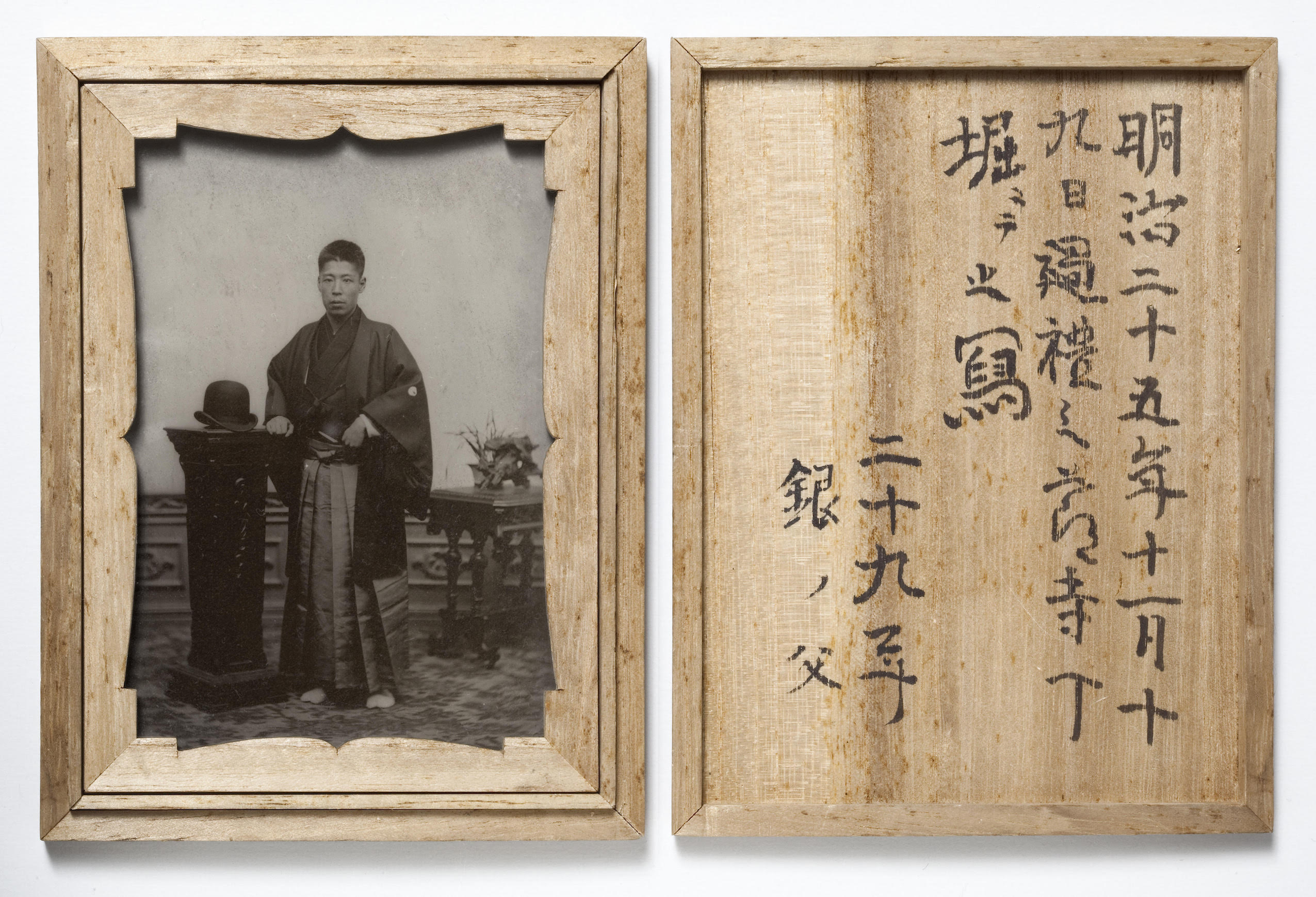

Makers unknown ( Japan), Standing Man with Bowler Hat on a Pedestal, November 19, 1892

ambrotype in kiri-wood case, with inscribed calligraphy in ink

12.4 x 9.5 x 1.5 cm (closed)

Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, Oxford

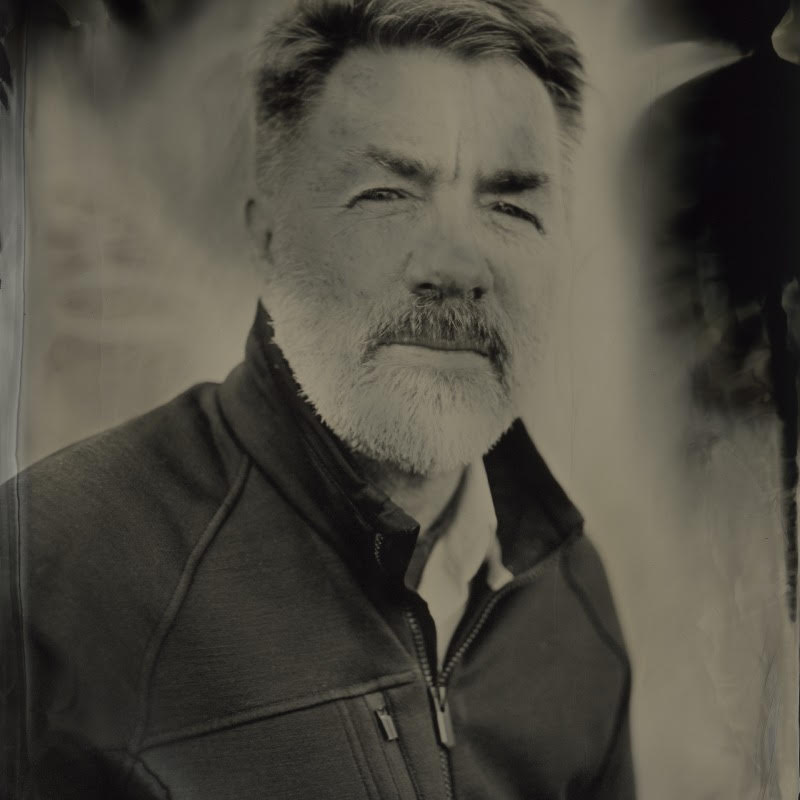

Makers unknown (American), Portrait of a man, c. 1910

Etched and painted tintype, paper mat, wood frame

48.5 x 43.5 x 10.0 cm

Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, Oxford

When photography forms part of a political aspect, such as, in the realm of historical propaganda, used in power relations, or as data or even surveillance, how is it navigated within the history of photography?

All photography is political; the medium itself embodies a quite particular relationship of time, space and subjectivity, and therefore denies the possibility of other such relationships. But photography also can and has been used for more specific political ends, usually to maintain the power of one class, race or gender over another. However, we should acknowledge that photographs are also capable of contesting established systems of power. They can be made into tools for thinking differently. All these aspects of photography need to be engaged in any good history of the medium. But I am not a photographer, or, at least, not a professional photographer. I am a historian. And so, my primary concern is with my own practice. How can historians make their readers think differently? How can our histories contest political inequities, including the ones previous histories have established and maintained? This what my work tries to be about.

Most of us have access to a camera, it is a constant feature of our lives, placed on our phones, what are your thoughts on how photography is regarded, the role of social media in that, and how or if that aspect of sharing photos, of storing images on the cloud, will enter the history of photography?

Photography has never been tied to any one technology or apparatus. Digital media of various kinds have been central to photographic practice for at least 30 years now. So those media will, of course, have to be incorporated into any future histories of photography (as they already are into mine). This means talking about, not just how digital photographs are produced, but also how they are stored, shared and distributed. It will also entail a critical discussion of the global economies of exploitation that make all this possible: of the corporate owners of both camera technologies and social media sites, the 24-hour factories in China that make cell phones, and the rare earths being mined in the Third World that go into them. There are particular genres of photograph that deserve close attention (the selfie is only one of them) and new practices worth examining in detail. One problem for historians to consider is the huge, almost overwhelming, scale of contemporary photography. How does one choose a representative sample of digital photographs from the billions being produced and shared every day? How does one track the effects of this massification of photography on our perception of any individual photograph? These problems seem unusually challenging. But, really, they are no different than the ones that have faced historians when trying to deal with the millions of photographs produced in past eras. In both cases, it’s a matter of deciding on the questions one asks of the material and the kind of history one is setting out to write.

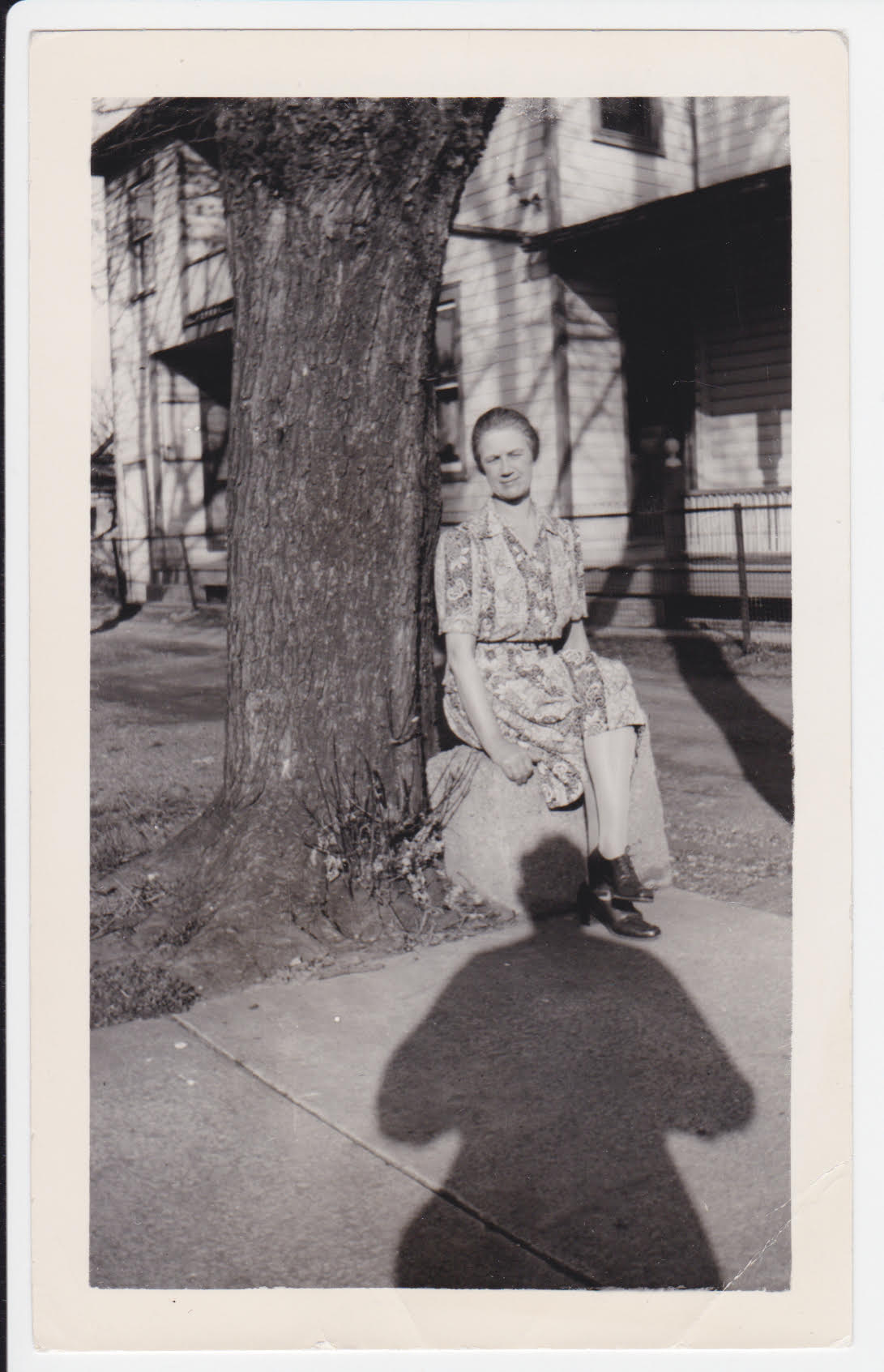

Photographer unknown (USA), Seated Woman, with Photographer’s Shadow, c. 1940s

gelatin silver photograph (on verso: “This was taken out front, boo the shadow”)

13.6 x 8.5 cm

Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, Oxford

A photograph might not be a true depiction of what it is capturing, what are some of the aims of photography and has that changed across time?

As early as 1844, William Henry Fox Talbot warned us that photographs do not necessarily resemble their referents, doing so by comparing the white mesh depicted in his photogenic drawing with the black piece of lace it had indexically recorded. Photography, he suggested, provides a truth-to-presence but not always a truth-to-appearance. Photographs testify that something was there to leave a trace in a light-sensitive substrate but don’t tell us what this something looked like to the human eye. Serious photographers have always recognized this truism, exploiting our naïve faith in the fidelity of the photograph to present fictional compositions as if they are not. Digital tools therefore merely facilitate what has been the case throughout photography’s history. In this sense, photography’s aims are driven by the collective desires of photographers and their audiences. I’m not sure those aims have changed a great deal over the past two-hundred years. Liars have always been with us, as have truth seekers. Whatever the available technology, people still value photography’s ability to record people and things in a way that is comprehensible and reliable. What has changed a lot is the ease with which those records can be shared with others, documentation and communication having become adjacent functions on all cell phones. Photographs are now messages more than documents, insistently omnipresent and yet also more immaterial and ephemeral than ever before.

I read that you have and are looking at the impact of digital photography on the environment, can you share with us some of the implications? Where do you think photography is headed, and how will the rise of NFT’s affect the field?

Like everyone else, I am of course alarmed at the rate by which we are destroying our own home. We know what we need to do to retrieve the situation—eat less meat, consume less energy, have less children—but we remain strangely reluctant to change our bad habits. Photography is imbricated in all this, as a contributor to, beneficiary of, and commentator on our current state of environmental degradation. I am interested in all these aspects of photo-ecology. I have students, for example, writing doctoral theses about a material history of photography, tracing how colonial exploitations of natural resources allowed silver (mined in Peru) and iodine (extracted from kelp in France) to get into the hands of photography’s pioneers. We need similar studies of the political economy of cell phones (dependent on rare earths) and web sites (which are huge consumers of electrical energy). I have written myself about the work of artists that reflects on this situation in a critical way, offering a photography that looks both inwards at its own ecological implications and outwards at the world around us. As to where photography is headed…? If I could predict the future, I would already be a wealthy man. However, I don’t think NFTs have much to do with photography so their impact on the field is likely to be negligible. Interesting art may be made for and with this new medium, but at the moment its most obvious equivalents are baseball cards, images of no pictorial value made financially desirable only through the imposition of an artificial rarity. There’s a lot to talk about there, but that talk would be about capitalism, commodity fetishism and inflation, not about artistic quality or the future of the photograph.

Geoffrey Batchen is the Professor of History of Art at the University of Oxford. His writing about art and photography has featured in numerous journals, books and exhibition catalogues and been translated into 21 languages. His books include Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (1997, and in Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Slovenian, Chinese, Italian and Ukrainian); Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (2001, and in Chinese); Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (2004); William Henry Fox Talbot (2008, and in French); What of Shoes?: Van Gogh and Art History (2009, in German and English); Suspending Time: Life, Photography, Death (2010, in Japanese and English); Repetition och Skillnad (in Swedish, 2011); Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (2016); Obraz a diseminace (in Czech, 2016); More Wild Ideas (in Chinese, 2017); Apparitions: Photography and Dissemination (2018) and Negative/Positive: A History of Photography (2021). He has also edited Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes's Camera Lucida (2009) and co-edited Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis (2012 + Turkish). His curated exhibitions have been shown at the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro; the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam; the National Media Museum in Bradford, UK; the International Center of Photography in New York; the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne; the Izu Photo Museum in Shizuoka, Japan; the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik; the Adam Art Gallery in Wellington; and the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, NZ.

'Negative/Positive: A History of Photography' by Geoffrey Batchen, 2020, Routledge.

Pictures courtesy of Professor Geoffrey Batchen