Youssef Nabil on

Photography and Film, Egypt, Memory, Life and Death

Youssef Nabil

Youssef Nabil’s art transports us onto dream like landscapes and journeys, cradled into a reality we can each connect with, projecting and unraveling a myriad of wondrous sentiments.

His work comprised of painted photography and film is rooted in Egypt, yet transcends the artist’s homeland, travelling across cities, notions and subjects that deal with migration, a feeling of exile, life and death, socio-political elements, the notion of belonging, as well as questioning the idea of home.

The artist’s work embodies an ethereal essence, by hand painting and colouring over his black and white photography, Youssef Nabil carries through a passion for Egyptian cinema, where his painted tints of blue or green seep into the works of art harbouring tints of emotions, feeding across onto the viewer’s gaze and replenishing our senses.

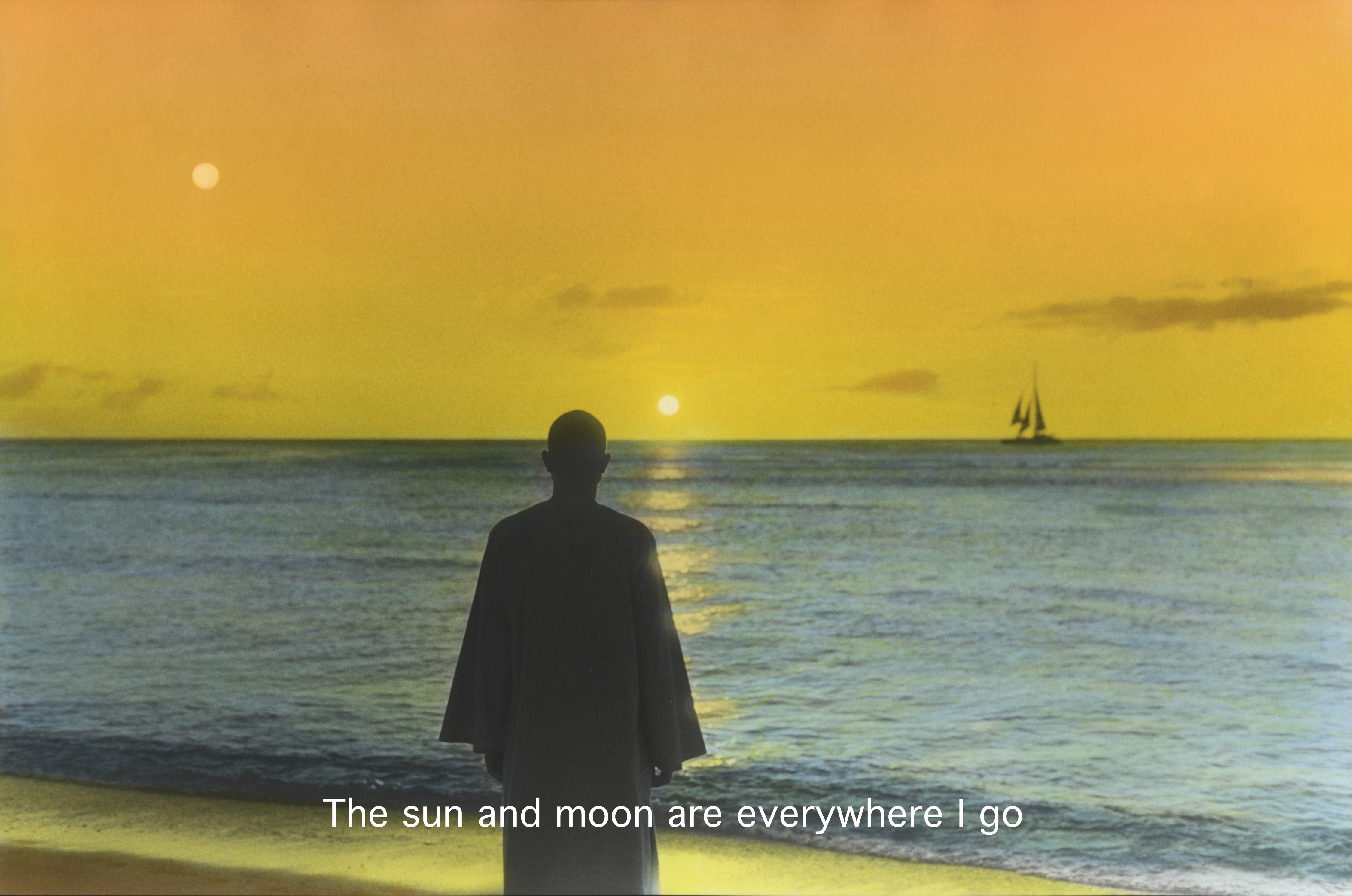

His body of work has included sets of self-portraits that bathe in the realm of the dream and sleep, with figures which take on a Rückenfigur angle, attached to a nostalgic element, yet looking ahead onto what the future holds or where destiny calls.

Youssef Nabil’s artistic ode to his friends, actors and fellow artists, which translate into a series of portraits, are both delicate and striking, fuelled by love and a strong sense of personal journey embracing a capacity for a collective and shared narrative.

The artist’s films explore substantial issues such as cultural norms, migration, loss, memory and what that entails in regards to our reflections on life. A set of films that run parallel to the artist’s photography, either visually coated in reformulating the orientalist perception, or poetically basking between dream and reality, life and death.

Both the subconscious and conscious flow into Youssef Nabil’s art, with a strong set of new emotive photographs from the exhibition ‘Memory of a Happy Place’ and the film 'The Beautiful Voyage’ on display at MENART FAIR with Galerie Nathalie Obadia. Visually enchanting and evoking a meditative quality, the artist places his figure and self-portrait in spaces that are close to his heart revealing the different parts of memory.

Light pierces through Youssef Nabil’s body of work, both literally, as photographic painted sunlight that stems from Egypt which the artist holds dear, as well as a light that is felt across Youssef Nabil’s work, one that speaks in serenity and consideration, shining onto our senses and through to our hearts. In looking for home or belonging, we may encounter it in art, and we certainly find it in Youssef Nabil’s magical and great works of art.

What first sparked your interest in photography?

I was quite an introvert as a child and teenager. Talking did not come so easily to me, and instead I recall being more interested in observing others, even when it came to my family members.

Now when I look back, I realise, that I was already then so absorbed in looking at life, which would later make me inclined to pick up a camera and take pictures.

The fact that I was also early on discovering the meaning of death, that we are all one day going to pass away, deeply marked me as a child and it was a traumatic feeling to conclude that we are not on earth for ever.

Photography can capture a moment and preserve it; after years gone by, we can look back at a particular time. That idea, alongside the perception that I could forever hold with me what I found precious, made me want to work with the camera and communicate with the world my observations.

Once I decided to be an artist, it was my only vocation.

You grew up in Egypt, could you tell us about some of your childhood memories and influences such as Egyptian cinema which have reflected in your art?

I wasn’t accepted into art or film school because of how the system was run, but I was a huge cinema lover.

Growing up in Egypt in the 1970’s and 1980’s, film was very accessible. I spent most of my childhood days at home watching movies on television, so much so, that it would be a film on whilst eating my dinner, another one on whilst doing my homework, I would even fall asleep in front of the TV, and when I went out, it was to go to the cinema.

Artistic and poetic film inspired and taught me a great deal. Italian and old Hollywood movies endeared me towards viewing film as a metaphor for life, and the craft of some Egyptian film directors drew me in.

When I started out in photography, I would ask my friends to come by and emulate film roles. With my camera I would then capture them in black and white. However, I had a need to see my work in colour, without wanting to use colour film, because I had viewed and still view it as another medium that emits a different visual quality. At that time, it was not as artistic to me, nor reflective of the cinema era I held dear, and so I took the decision to paint and hand colour my black and white prints, using the same old photography technique to keep that magic alive I had admired from the technicolour Hollywood films, as well as from the hand painted posters and billboards on view across the streets of downtown Cairo. I actually collect those posters, it’s a real passion.

There are particular colours that I am always captivated by and use, such as the colour blue, which is reminiscent of The Mediterranean Sea. Throughout the years I tried out different tones, but I always came back to the same shade of blue, one that immersed itself into the photographs and has now become embedded in most of my work, alongside a particular shade of green I use quite often. Turning a photograph into a painting, whilst making it apparent that underneath the layer of paint there is an actual photograph, is my way of seeing things.

Self-portrait with The Nile, Luxor, 2014

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

What has set in motion your ideas for your body of work? Have they flowed depended on a certain time in your life?

When I photograph someone, something has to move me, there has to be a bond with the person, especially artists, because I include them to take part in my own story, and see them as part of a family. Every person I capture is someone I admire, and through photography, I hold on to that moment. Now when I look back at the images, I remember how I used to feel at that particular time.

I started shooting self-portraits when I left Egypt for Paris, I was alone and I had a need to relay what I was feeling. As the emotion was raw in the moment, and I was available, it quite naturally commenced that way, leading to a continuous body of work comprised of self-portraits.

Other works such as the film ‘I Saved my Belly Dancer’, arose due to the developments in Egypt after the 2011 revolution and when the Muslim Brotherhood came to power. Belly dancers were being attacked and the establishments they danced in were forcibly being shut down.

At the time I was in New York and had read that twelve nightclubs were closing. It brought back conversations my friends shared with me in regards to how countries can shift towards certain norms and laws that may have once seemed inconceivable. I became very worried about Egypt. I wanted to save the memory of the belly dancer, because that figure is one that I loved and grew up with watching on television, admiring that beautiful form of art, which is very sensual and authentic.

As soon as there was a backlash towards this art and the nature of liberty, something happened inside of me, I was angry about what I was reading and hearing and it triggered all sorts of emotions which I wanted to share and speak about through my own art.

%20MD.jpg)

I Saved My Belly Dancer # XII, 2015

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Between that film project from 2015 and now, I was developing the body of work for my latest exhibition ‘Memory of a Happy Place’. Throughout those seven years, two of them were plunged in a global pandemic, and I truly wasn’t in the mood to do anything, my father passed away, and I was very worried about my family.

When the world started opening up again in 2021, I reinstated working on the new photographic series, but something even more personal had to come out and reveal itself for me to get into the right frame of mind, I had to go through a new personal experience, and so in 2021 was born my latest film ‘The Beautiful Voyage’.

The Beautiful Voyage, 2021

Film 8 min

with Charlotte Rampling and Youssef Nabil

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Memory of a Happy Place, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

How much does perception feed into ‘The Beautiful Voyage’ and the series of photographs from ‘Memory of A Happy Place’?

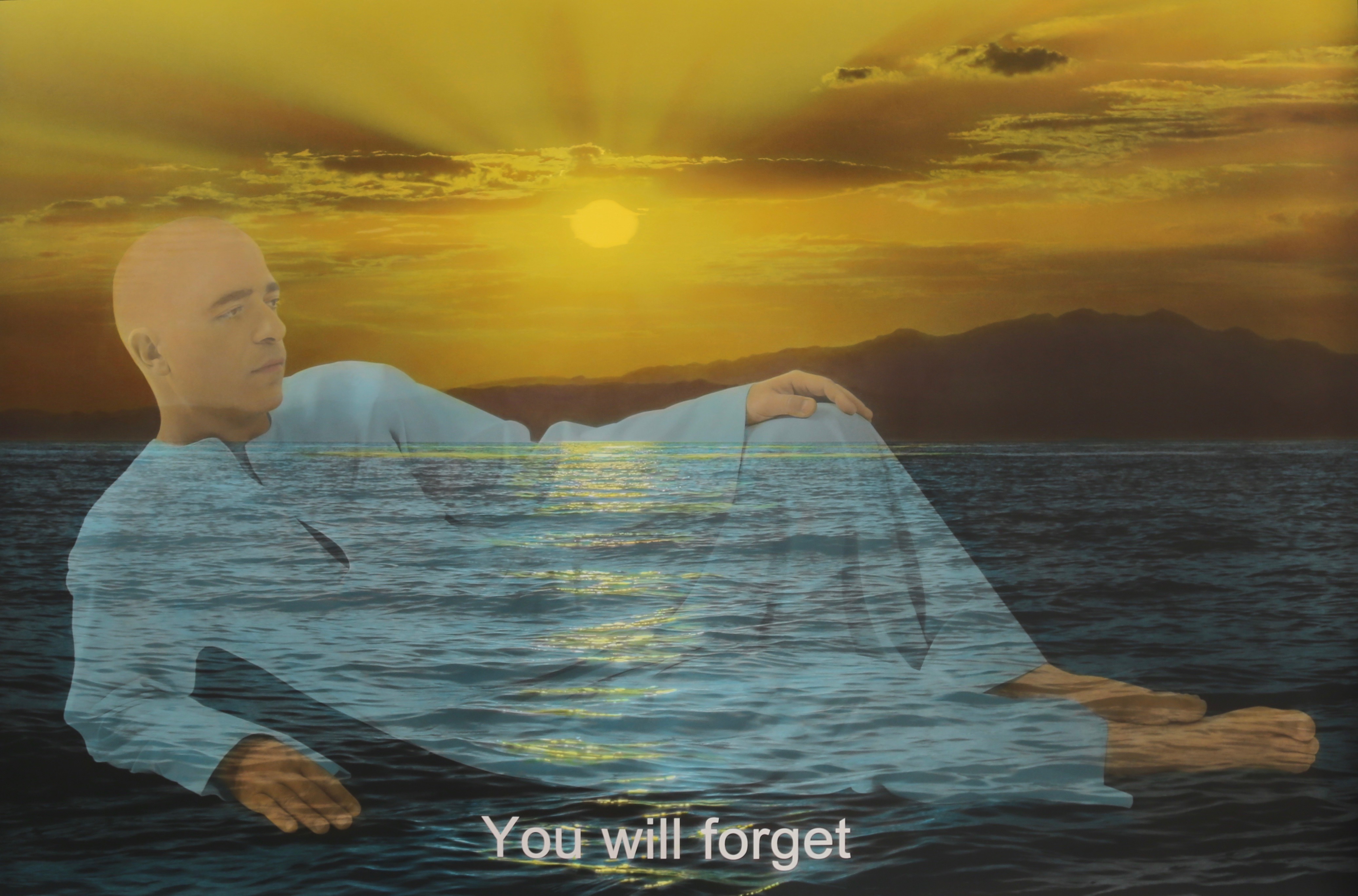

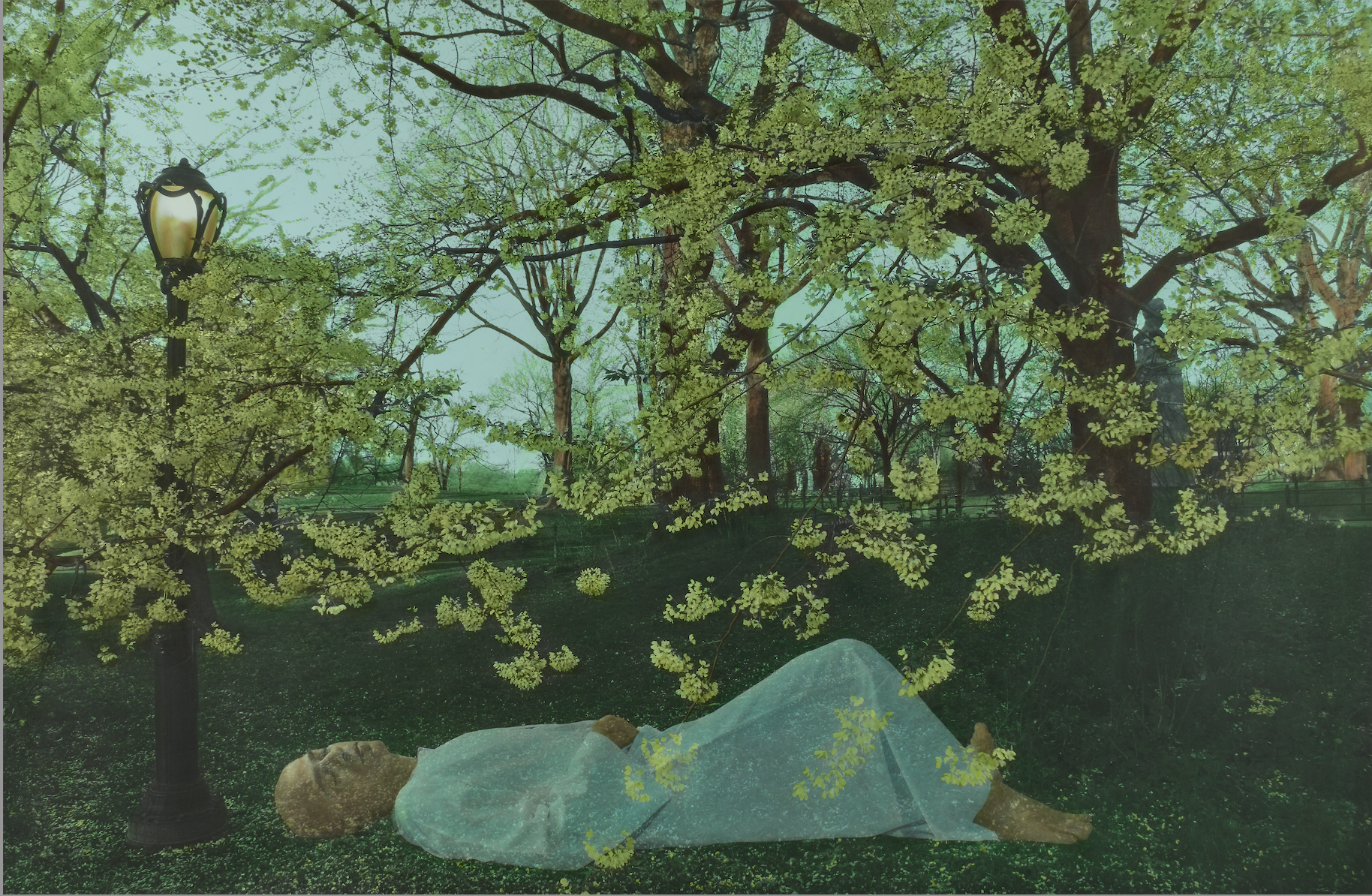

The photographic works and the film ‘The Beautiful Voyage’ which featured in the exhibition ‘Memory of A Happy Place’ address issues I have been preoccupied with.

Part of that is the memory, as worded in the title, the fact that we have an idea of our past, a memory in our mind which we carry, and yet, when we try to remember things, they are never as sharp or as romantic as we thought they were.

The photographs also trace geographical places that have marked me. The images cut in half or more, are often superimposed to project the imperfection of memory, but also that very idea, that in fact, everything we perceive is a memory.

You will forget, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie

No one knows but the Sky, 2019

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Self-portrait in the Park, New York, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

‘The Beautiful Voyage’ is about leaving home trying to find home but also it is about our existence. In the film Charlotte Rampling recites the text I wrote, which reinforces the notion of memory, as well as exploring life and death, age, leaving home and questioning where is home.

I write a lot, but I have never shared that publicly, it is the first time I am including my own full text through my art, as well as the first time my mother is participating in my film, narrating one of my favourite poems, ‘Ithaque’ by Constantin P. Cavafy.

Though it was a very personal project, it is also a universal one, as the questions I dived into in relation to the nature of us as human beings, and to leaving home, are I think notions that many people can relate to.

Leaving Egypt your homeland, nostalgia and the reality of things fuse together, how have you experienced that?

I left Egypt many times, but in 2003, I knew that I was moving out of the country, however I hadn’t taken into consideration how my feelings would subsequently unfold. I assumed that by being based in Paris, I could go back and forth to Egypt without the move having impacted me, but, with an experience like that, something changes in a person, and the first film I made entitled ‘You Never Left’ spoke about those emotions. It tackled my personal state once I decided to migrate from Egypt, as well as the notion of death, because often, leaving home when one has to, can feel like a death.

You Never Left # I, 2010

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie

As soon as I retreated from Egypt, I felt like a visitor everywhere else I found myself in, places I would go to would momentarily feel like home, but it wasn’t home.

I would stay somewhere for quite some time for work, for instance when I was invited by the Ministry of Culture to live in Paris, but then I would have to leave again; a similar pattern I have encountered throughout my life.

When I have returned to Egypt, in my mind it has been as though I was a ghost visiting a familiar place. Locations I used to go to or drive past, fuel me with a sense that I was not supposed to be there, and I should instead once more depart.

It’s actually quite disturbing living in between two entities, leaving one’s homeland often equates with a search for belonging. I think anyone who has had to endure that, pursues that feeling of belonging.

I have learnt that Egypt lives within me wherever I am.

In conversation with André Aciman for the book that accompanied my exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi, we discussed the consequences of leaving Egypt, as he had experienced that too, and we each considered where we would eventually like to be buried, as I think it is an indication of where a person believes they belong. In my thoughts, when that day comes, I would like to be buried in Egypt. I see this topic as part of life and something we need to think of, like planning a trip.

Say Goodbye, Self-portrait Alexandria, 2009

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

The Sun and Moon are everywhere I go, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

That element comes into your photographic series in the exhibition ‘Memory of A Happy Place’, it is supported by a transparency technique, how did that come about and why?

This inspiration also came from the film world, it stems from a cinematic technique called dissolve, where an image superimposes over another one.

The concept of transparency within that body of work reflects the idea that we are both here in this world and at the same time we are not present, all living life fully aware that our time on earth is not permanent. The work echos that everything in life is ephemeral.

Connected to you by every Sea, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

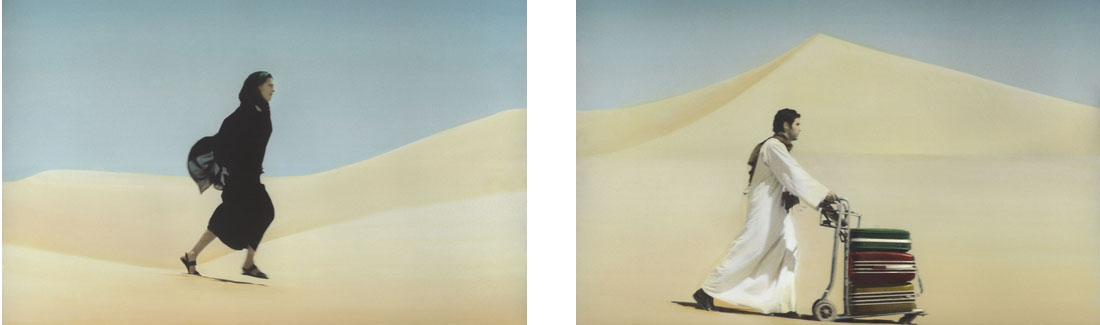

Here to Go, 2019

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

The figure is placed across different landscapes, perhaps searching for that feeling of belonging you were mentioning, they assume the Rückenfigur technique, captured from the back, contemplating what is in front of them, how did that develop and what would you like to convey through it?

Most of the time my self-portraits are taken from my back, but I have previously shown my face in my photography when it felt relevant.

I don’t pursue revealing my face that much in my work, as through the self-portraits I am referencing us all. It’s about human nature and an experience we each one of us might have gone through or can relate with.

The figures or self-portraits could be anyone, it’s not necessarily my own being, at the core of my work, is the viewer being able to connect to a figure and find themselves within the art.

Similarly in my texts in film or on the photographs the ‘I’ renders itself available to belonging to other people’s narrative. I also consider my films as self-portraits.

What motivated you in ‘The Beautiful Voyage’ to take that leap and be in the film?

On my previous films, I had worked with actors, though each one of those films are a part of me and my journey, it is only in this latest one, that I had decided to include myself, as it became too personal not to, there was a need for the trajectory of the story that I feature in front of the camera film.

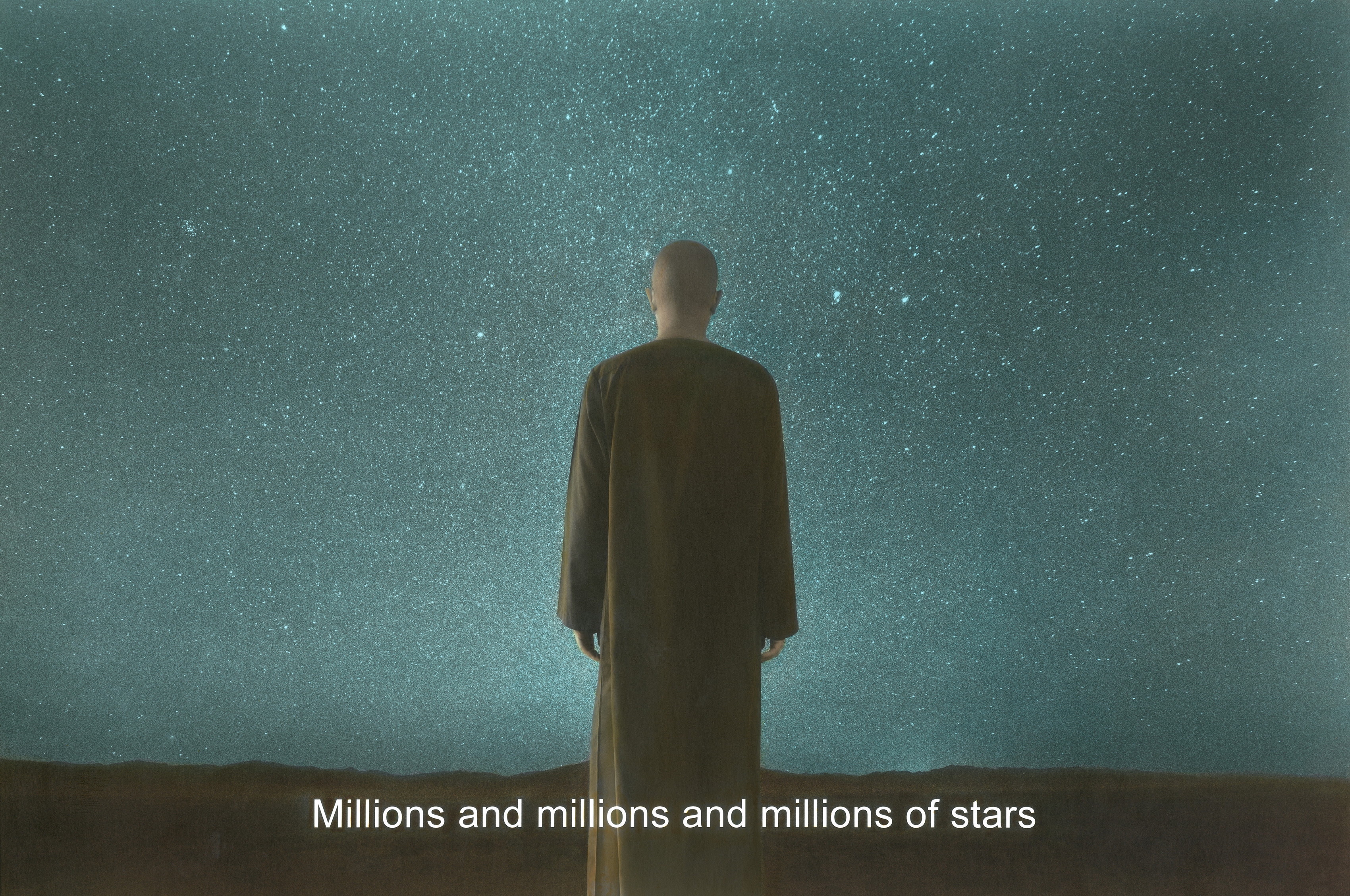

Millions and Millions and Millions of Stars, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Self-portrait with the Moonlight, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

How do you read the realm of the dream, sleep, and the notion of spirituality, which is rooted in most of your art, whether through nature or the figure?

We are here, part of this physical world, but everything we have ever owned will belong to other people after we leave; once we pass away. There is this surreal idea that we inhabit, experiencing life whilst also knowing that we are not going to last forever, and we don’t even know until when.

To me it makes absolute sense, that we are not just this physical body, I think there is something else, a spiritual element that might be hard to define, but I see it in nature, I see it in everything.

I see this spiritual element everywhere, even in dream, and it is referred to in 'The Beautiful Voyage' when Charlotte Rampling says: "When I close my eyes every night to sleep, I see everyone I love present and alive, even if they are no longer part of life. When I wake up, I always have the same feeling, that it was not a dream, it was real."

The Dream, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

At MENART FAIR from the 19th to 22nd May at CORNETTE DE SAINT CYR – PARIS

All pictures courtesy of Youssef Nabil and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Images © Youssef Nabil

Interview as part of Art Breath x MENART FAIR

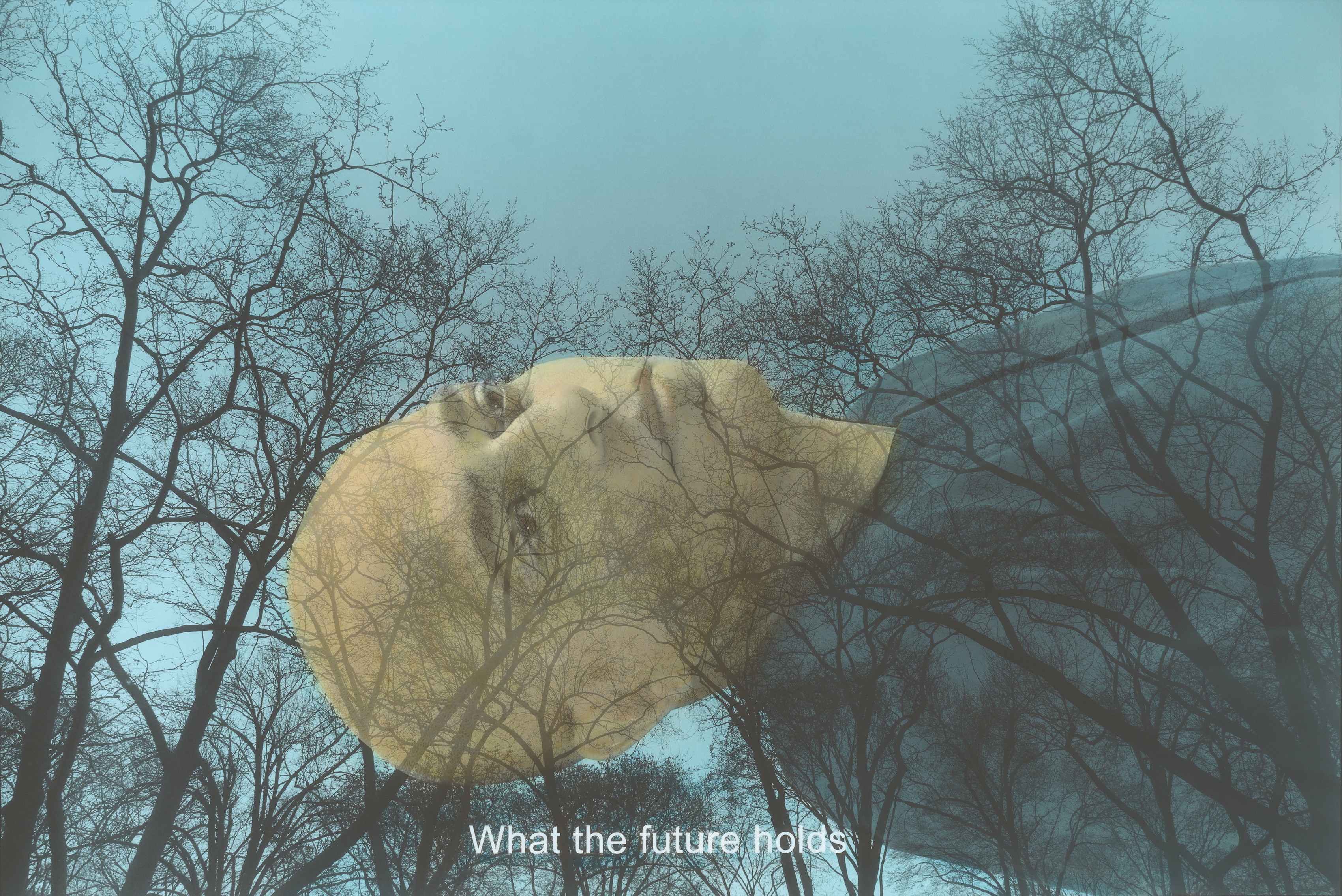

What the future holds, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels

Youssef Nabil was born in 1972 in Cairo (Egypt). He lives and works in Paris (France) and in New York (USA). Nabil began his career in 1992 by staging tableaux in which his subjects acted out melodramas recalling film stills from the golden age of Egyptian cinema. The past decade also testifies to the artist’s foray into the medium of film; with "You Never Left", 2010, "I Saved My Belly Dancer", 2015, "Arabian Happy Ending", 2016, and "The Beautiful Voyage", 2021.

Youssef Nabil’s International solo and group exhibitions include: in the USA, at the Pérez Art Museum (PAMM) in Miami, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Studio Museum in Harlem and Aperture Foundation in New York, the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art and Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) in Savannah and in Atlanta, and the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh; in Canada, at the Aga Khan Museum of Art in Toronto ; in France, at the Centre Pompidou, Maison Rouge – Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Institut du Monde Arabe and Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, the Frac Normandie in Sotteville- lès-Rouen, the Friche Belle de Mai in Marseille, the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, ; in Belgium, at the Fondation Boghossian and Maison Particulière in Brussels ; in the UK, at the British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Newcastle ; in Germany, at the Museum für Modern Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt, the Kunstmuseum in Bonn, and the Gemäldegalerie Staatliche Museen in Berlin ; in Spain, at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) in Barcelona, the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville, and the Instituto d’Art Modern in Valencia ( IVAM ) ; in Italy, at the Villa Medici in Rome, the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, The Palazzo Grassi in Venice and the 53rd Venice Biennale, Unconditional Love ; in Qatar, at the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha; in Mexico, at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City; and in Mali, at the 5èmes Rencontres de la Photographie africaine in Bamako, during which he was awarded the Seydou Keïta Prize. In 2020/2021, Youssef Nabil had his first retrospective exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, titled Once Upon A Dream.

Youssef Nabil's work is part of various international collections, among which: in the USA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Pérez Art Museum in Miami (PAMM), the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, and the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art (SCAD) in Savannah; in France, the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the Collection François Pinault, and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris; in Switzerland, the Collection UBS Art in Zürich; in the UK, the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London; in Angola, the Sindika Dokolo Foundation in Luanda; in Greece, the Photography Museum in Thessaloniki; in Qatar, the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha; in the United Arab Emirates, the Guggenheim Museum in Abu Dhabi; in Mexico, the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City.

Four monographs have been published on Youssef Nabil's work – Sleep in My Arms (Autograph ABP and Michael Stevenson, 2007), I Won't Let You Die (Hatje Cantz, 2008), Youssef Nabil (Flammarion, 2013), and Once Upon A Dream (Marsilio, 2020).

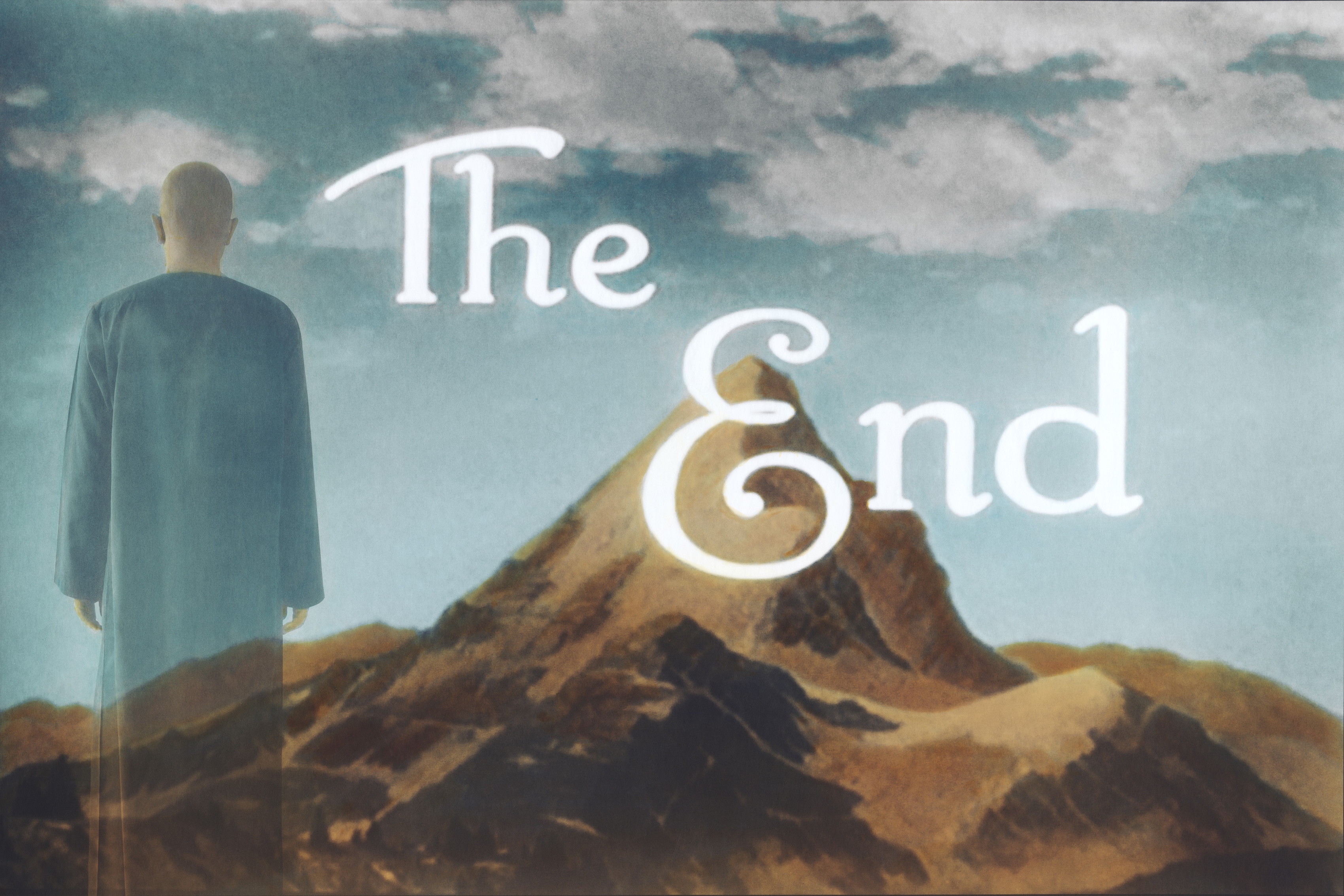

The End, self-portrait, 2021

Hand colored gelatin silverprint

© Youssef Nabil, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris / Brussels