Elettra Stamboulis on Zehra Doğan,

on Their Connection, Activism, Zehra's Art, imprisonment,

Her Thoughts and Current Path

.png)

Zehra’s art is moving and powerful, her impressive drawing skills, the brushstrokes, movement, pain of the figures take hold of the viewer's attention with an emotion that is felt even prior to learning how her artworks came about.

The art documenting the artist’s pain and imprisonment, intensify that very emotion and informs us about war as well as the power of art to relay perspectives that may otherwise be disregarded.

Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan was born in Diyarbakır, Turkey and became one of the founders of Turkey’s first women’s news agency, JINHA.

In 2016, Zehra was reporting from Nusaybin, a town on the border with Syria mainly inhabited by Kurds. After the city of Nusaybin was under military attack, Zehra drew what she had witnessed.

One of her paintings was based on a photograph she had seen on social media depicting Turkish military victory. Her own artwork was painted to reflect on their military aggression and lives lost. After her own artwork went viral, she was arrested, charged for allegations of propaganda, and imprisoned by the authorities in July 2016, released in December of that year, sent back to prison in June 2017, and finally released again in 2019.

During her incarceration in a number of prisons, Zehra drew what she felt and was experiencing with the very limited materials she could obtain or found substances. At certain times she was able to teach art to the other women prisoners, using her art to establish links and talk with the women and even experiment with collective ways of creating art.

Feeling empathy with Zehra Doğan and her situation, renowned curator and writer Professor Elettra Stamboulis went on to curate Zehra’s first solo art exhibition in Italy.

We spoke to Elettra about Zehra’s art, thoughts, her imprisonment and what she is currently working on.

What first drew you to Zehra's art?

I’m part of a net of activists who supported Zehra and other detainees’ release from Turkish prisons. Prisons in Turkey are filled, not just with political activists whose only offence is to speak out against the current politics, but also with journalists, intellectuals, artists such as the young musician Nudem Durak, or the writer Aslı Erdoğan.

In 2018, my husband Gianluca Costantini, an artist and online activist, drew a picture of Zehra which touched me deeply because she appeared to be so young, which of course she is, but I had this sensation that she could be my daughter.

Zehra Doğan by Gianluca Costantini

https://www.channeldraw.org/2018/07/07/zehra-dogan-turkey/

It was first about humanity and then art.

When I was invited to Morlaix by the Kedistan association for Zehra’s first art exhibition in Europe, I saw to which extent she truly was an artist and fell in love with her art.

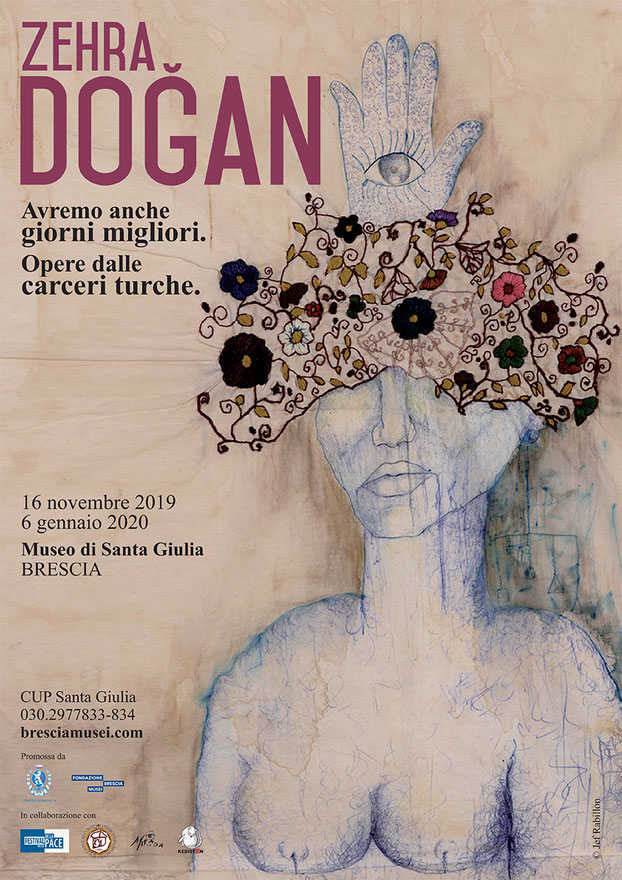

She was still imprisoned then, but I read some of her letters addressed to Naz Oke who is part of the Kedistan association. I decided that my small contribution would be to curate Zehra’s first solo exhibition and catalogue it. I wanted her to be recognised as an artist and not as a victim, a continuous risk. We were able to hold the exhibition “We will also have better days – Zehra Doğan, Works from the Turkish prisons” in Bresci, Italy.

Poster for the exhibition “We will also have better days – Zehra Doğan, Works from the Turkish prisons” curated by Elettra Stamboulis featuring in poster the artwork "Fatıma'nın Eli" (Fatma's hand) by Zehra Doğan

58 x 34 cm. Pillow case, tea, coffee, embroidery, ballpoint pen. 11.2018, Diyarbakır Prison.

Were you able to exchange letters with Zehra while she was in prison?

Zehra only speaks Turkish and Kurdish, so communicating directly with her was not possible. It was also very difficult for Naz Oke to ensure that her letters were delivered. Naz was our window and insight into what was happening. The letters she sent to Zehra were later published in French and they will now be published in Italian.

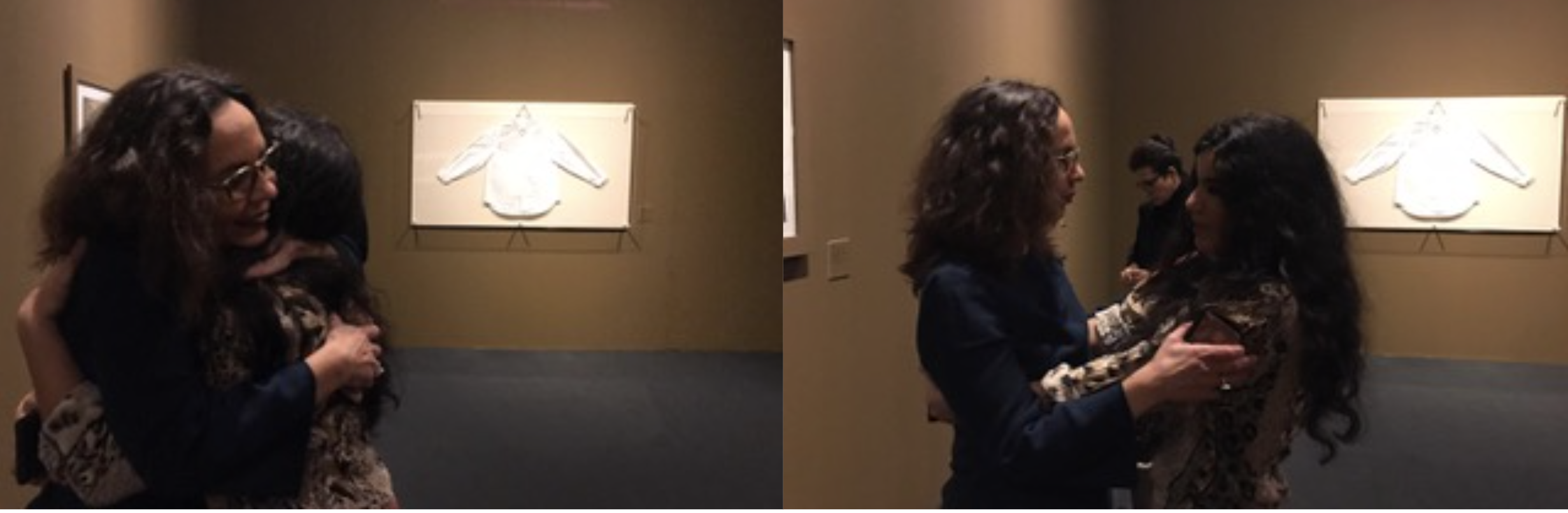

I met Zehra in person for the first time when she came to Brescia on the 23rd of November 2019 for a performance in honour of Hevrin Khalaf.

It was exciting, but at the same time it was like being reunited with an old friend or sister.

Elettra Stamboulis and Zehra Doğan

Art Performance by Zehra Doğan at the Santa Giulia Museum, Brescia for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

Could you share with us a little on the mobilisation and support for Zehra's release

The mobilisation was huge and involved many people, but also artists such as Ai Weiwei, Gianluca Costantini and Banksy.

The support was great and important; when the focus is on a person, it may ensure that their time in prison is safer.

Unfortunately though, it was not enough to propel her release, and she remained in prison for the duration of the days she was convicted.

Our fear intensified towards the end of her sentence, as she was moved to Tarsus prison, which is a high security one with added difficulty to access prisoners. Her move felt like a signal that there was no chance of freeing her.

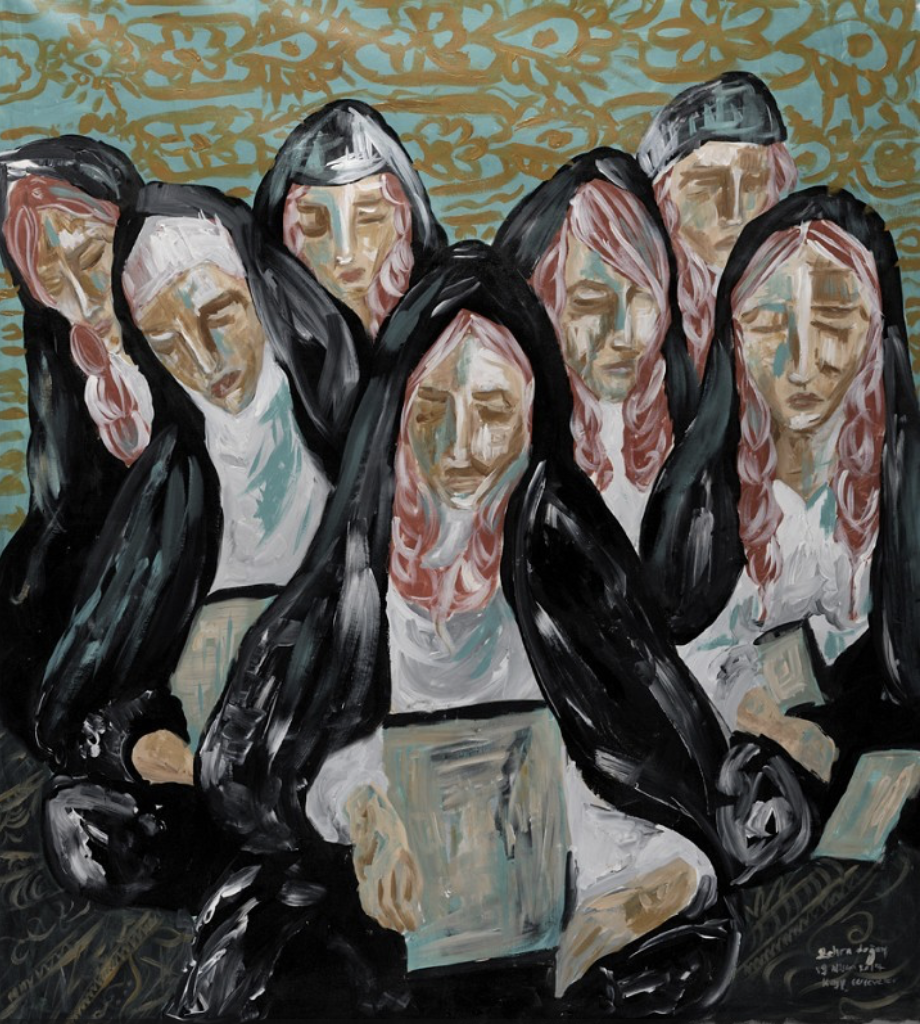

Kayıp Çerçeveler (Lost Frames) by Zehra Doğan

138 x126 cm framed. Acrylic on canvas. 2017, Clandestine days, Istanbul. Prometeo Gallery

What happened to the art she created during her time in prison? How much was she able to get out?

Very little, what she could hide under her clothes when her mother went to visit her.

Around that time, Zehra’s parents realised the power of their daughter’s art. They used to place her artworks in the middle of a room surrounded by her large extended family and act as her first ‘art critics’, interpreting the artworks. At the next opportunity Zehra’s mother could visit her in prison, she would relay all the family’s comments and ask her if any of the interpretations were correct or not.

In particular we, (and I say we, because it’s a loss to us all) lost a large part of Zehra’s diary, destroyed by the prison service.

The activists supporting Zehra were critical in helping transfer some her work to France. It was like running a relay, and the objective was to preserve Zehra’s work and the women prisoner’s heritage.

It’s an important point that underlines Zehra’s art made in prison, it is a collective memory and a heritage.

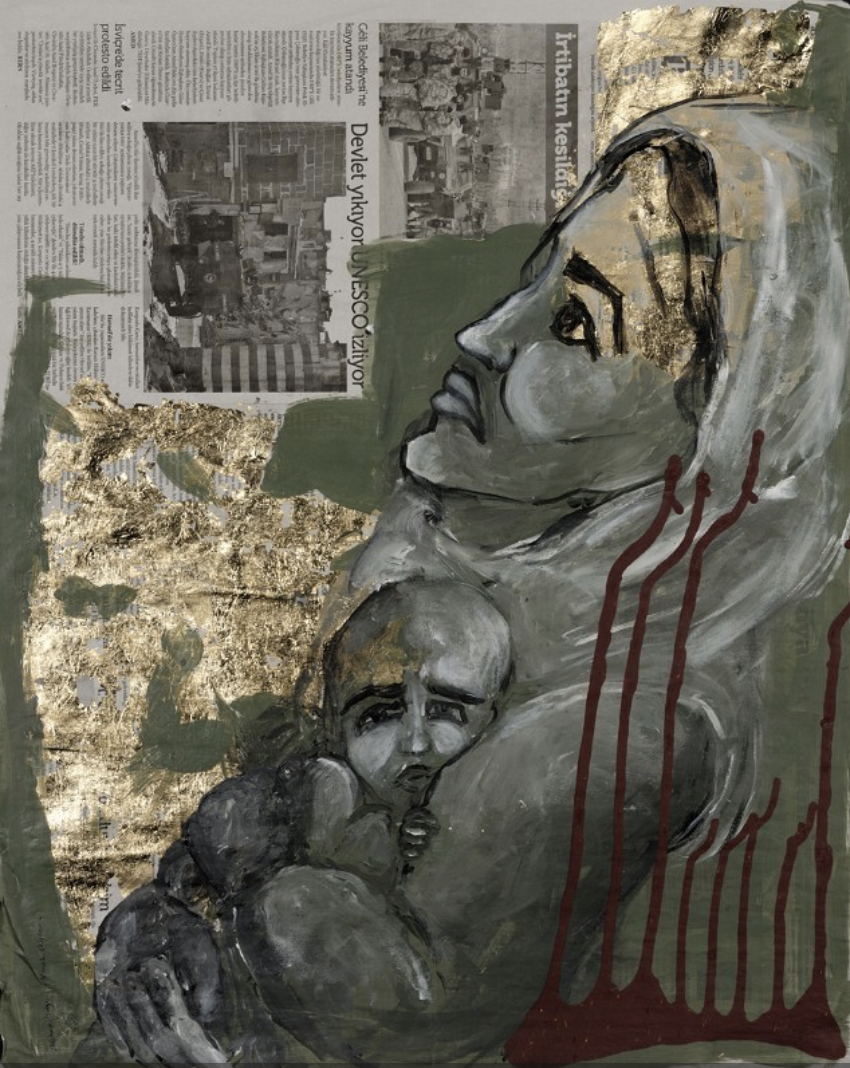

Untitled by Zehra Doğan

67 x 56 cm, (59 x 73 cm framed). Acrylic on newspaper. 2017, Clandestine days, Istanbul.

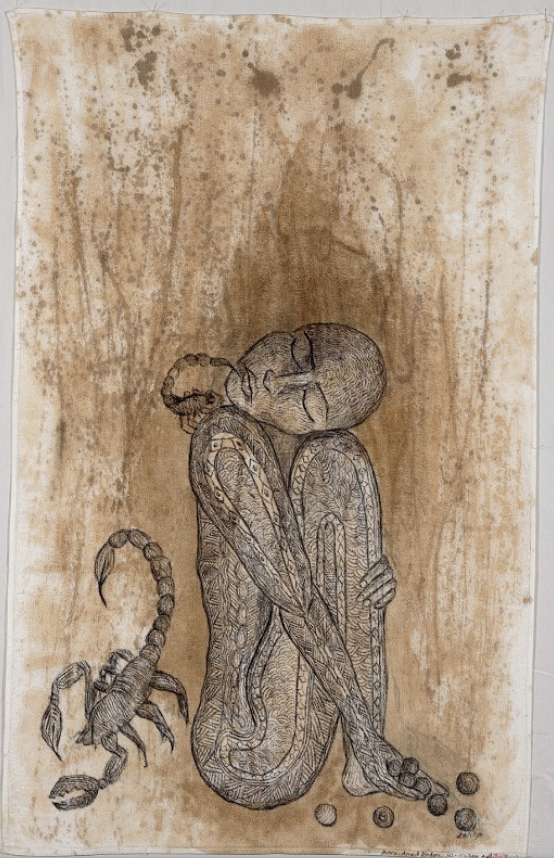

"GİRTÎ 3/4" (Captive) by Zehra Doğan, 45x60 cm. 2016, Mardin prison.

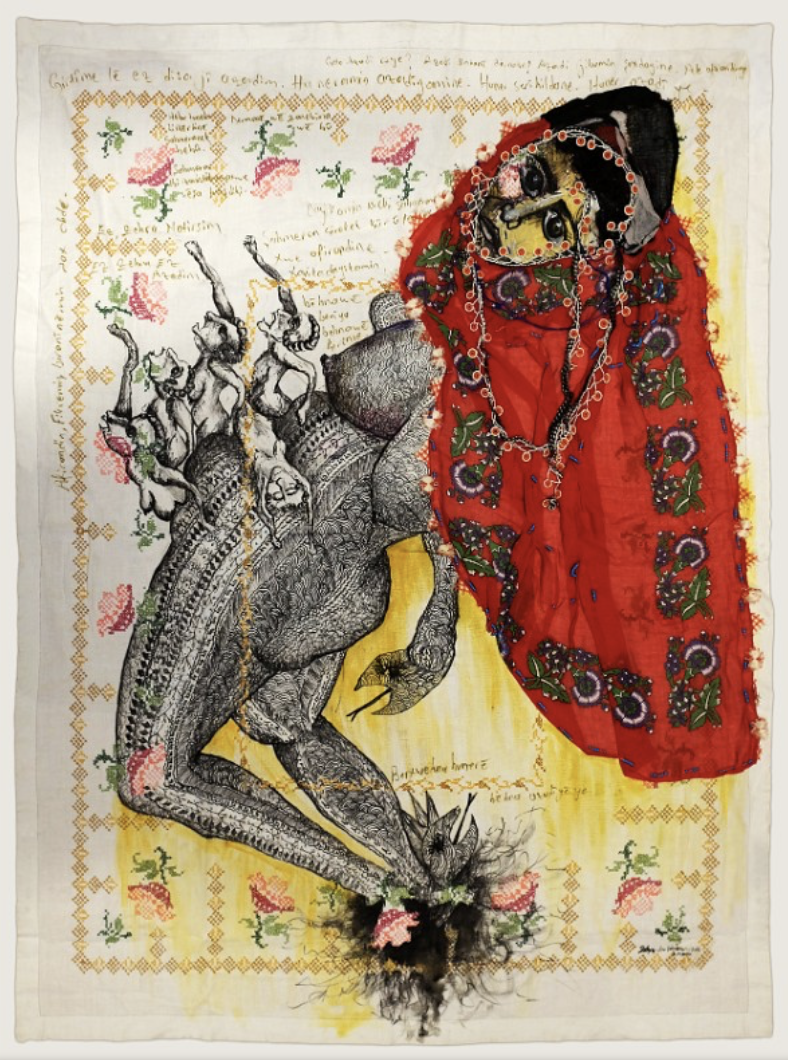

Êşa Şahmeran (Şahmeran's pain) by Zehra Doğan

114 x 151 cm On bundle scarf, felt pen, acrylic. 2016, Mardin Prison.

Jinén Li Hember (The women in the courtyard) by Zehra Doğan

220 x 156 cm. Felt pen, coffee, tomato paste, on fabric, entered the prison in the form of a skirt. 2018 Diyarbakir prison.

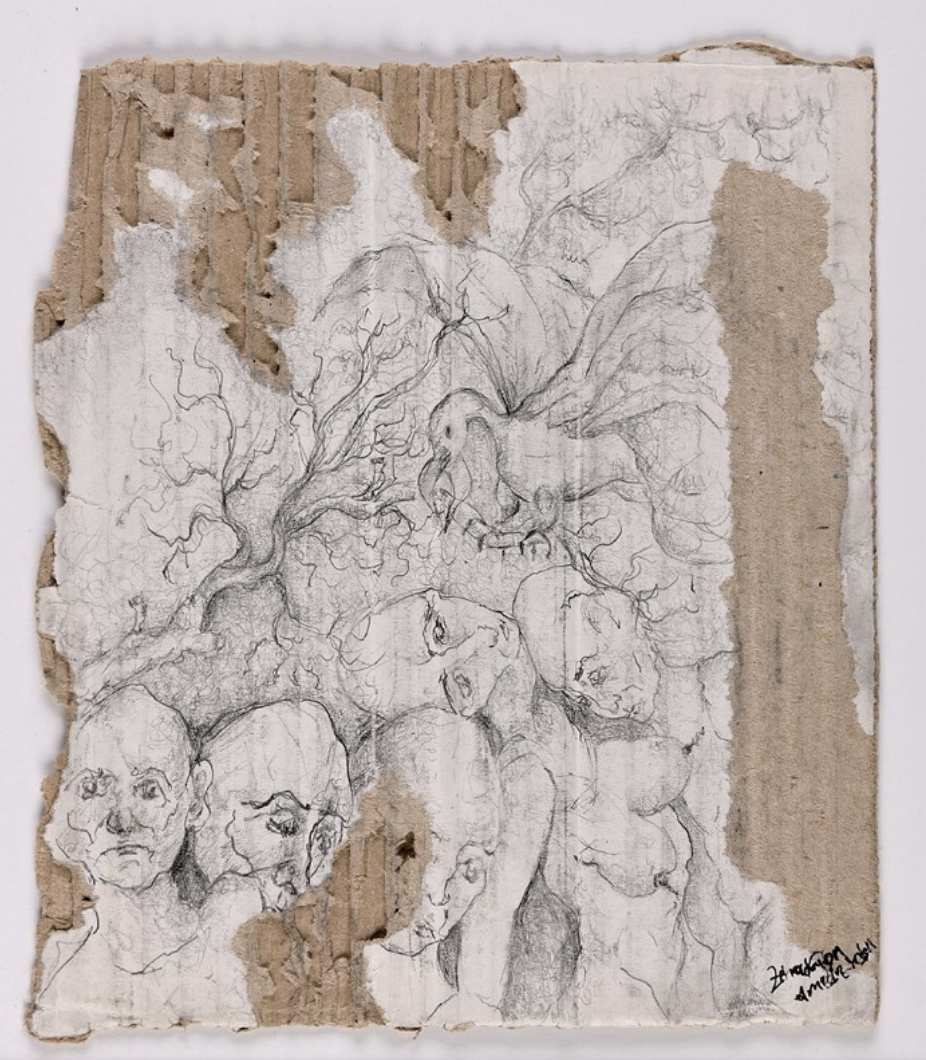

"ÇALINTI HAYATLAR -2" (Stolen lives 2) by Zehra Doğan

18 x 16 cm. Pencil on cake packaging carton. 2018; Diyarbakir prison.

How was she able to draw whilst in prison?

She used what she could, coffee, tea, the remains of food (saffron, pomegranate), cigarette ash, even menstrual blood.

An accidental stain would become an opportunity to engage in a discussion with other prisoners about what its shape reminded them of. From that, Zehra would create an image.

Drawings were done on the back of Naz’s letters, on towels, on the prison’s sheets and on the aluminium foil of cigarette packets.

Throughout the years, she was moved to different prisons. The situation was a little better in the first one before her trial, where there was more of a possibility to draw or paint.

"DORŞÎN" by Zehra Doğan

120x120 cm. Acrylic on canvas. 2016, Mardin prison

"ARKADAŞ" (Friend) by Zehra Doğan

30 x 21 cm. Pomegranate peels, clandestine paint, food oil, cigarette ash. 2017, Diyarbakir prison.

.png)

"Krasê Yadamin" (My mother's dress) by Zehra Doğan

230 x 135 cm. Felt pen, coffee on dress. 2018, Tarsus prison.

Untitled by Zehra Doğan

68 x 39 cm. Set of placemats and three towels that I had bought for the house in Nusaybin, brought to the prison by my sister. Menstrual blood, felt pen. pencil.2018, Tarsus prison.

Zehra's brushes

The administrations of Diyarbakir and Mardin Prison prohibited all artistic material. These brushes were made with the hair of my imprisoned friends and the feathers of the birds nesting in the barbed wire of the airing court.

What was Zehra’s first foray into art, and when did she first fuse politics into her art?

For Zehra, there are no boundaries between the two. As she wrote in her diary

“When I was working as a journalist, I could not draw, but, drawing is a part of me, and a part of me is the Kurdish people’s struggle. In my paintings, light, colours, images are there standing for Kurdish history and their experiences. The creative anger couldn’t be tamed”.

Art for Zehra is politics, and politics gestures at art, so it’s impossible to find an ante quem.

If you are from that land, then you are drenched in politics from your birth. For Zehra, drawing was a way to express what she lived.

When she founded together with other women journalists JINHA, a feminist and completely women led press agency, they thought “we will write without thinking about what men will think of, because when women write, and we hold up a mirror to society, then the image of men in the mirror starts to fade”.

That fading mirror is the key to Zehra’s practice.

She had and has two weapons, writing and drawing, and she decided not to leave them even in conditions of seclusion.

Does Zehra feel that her art has changed previous to her incarceration?

Yes, prison changes you. Before her time in prison her journalistic work took priority. To a certain extent, it did so in prison too, as what helped her start teaching art in prison, was the publishing of Ozgür Gündem, the prison’s newspaper which was all done by hand. So journalism and art really became one at service of the other. The relationships with the other prisoners, not only the political ones, were deep and helped her to understand the power of her brush. She also sometimes feels down, or that she is a lazy person, so the discipline of the work with the prisoners helped her face her depression (which is always present in prison...).

Which painting has stayed with her most?

She is very linked to her artwork "Muğdat Ay, killed at the age of 12”. She was there when the boy was shot at in Nusaybin. They tried to save him and they carried him to the emergency hospital, but he died holding onto his marbles in his hands.

Her painting is not just a depiction of a war victim, it is a real life tragedy and a document of what happened.

"Muğdat Ay" (*Muğdat Ay, killed at the age of 12, in Nusaybin, in February 2016) by Zehra Doğan

144 x 92 cm. On towel, ballpoint pen, tea. 05.2018, Diyarbakır Prison.

How does she feel now being away from her homeland?

She feels unhappy and senses a strong nostalgia for her homeland. She is far from her family, her friends, and without a home or a permanent residency. Of course she is proud and happy about her work and research in Europe, where she had the opportunity to show her art to an international audience and give voice to the other women who are still in prison. But on the other hand, she is forced to stay away from her home and that’s not what she would have wanted for her life.

She takes power from the everyday struggle in Kurdistan, and it’s the place where she feels she belongs. Her real desire is to have an exhibition in Diyarbakir which is impossible at the moment, but who knows. Some very brave curators in Istanbul organised a private exhibition in the town. So maybe the time will come soon.

"Kaç-GÖÇ" (Migration) by Zehra Doğan

165 x 98 cm. 2016, Mardin prison

Neynik (Mirror) by Zehra Doğan

On carpet, acrylic, felt-tip pencil. 2020 Lugano, Italy.

Prometeo Gallery. Private Collection.

What is Zehra working on now and what are her hopes for the future?

At the moment she is working on a new project commissioned by Gorki Theatre in Berlin. She has a very busy ongoing agenda of conferences and commissioned work. Her letters to Naz Oke will be published in Italian, as will the Graphic Diary she started in prison and we are working on a new exhibition in Greece.

Currently an exhibition hangs at the PAC in Milan, but museums are closed, so circumstances to show her work to a wider public are not easy even in Europe. We are all experiencing a soft form of reclusion. I hope that this collective experience will give us more empathy. Foucault describes The Punitive Society, the notion of disciplinary power underpinning everything, which in modern Turkey already seems largely set in motion.

Zehra reminds me of a very well known quote by Gramsci ‘pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.’ Our hope is to destroy the patriarchy, right? So, I suppose that she knows that maybe we will not be able to see that happen, but still we fight for it...

Untitled by Zehra Doğan

213 x 107 cm cm framed. Acrylic on canvas. 2017, Clandestine days, Istanbul.

Prometeo Gallery. Private Collection

Zehra Doğan is a Kurdish artist and journalist born in Diyarbakır/Turkey. She graduated from Dicle University’s Fine Arts Program and became one of the founders of Turkey’s first women’s news agency, JINHA, which she worked for from 2010 up until 2016, when it was shut down by government decree. During her journalistic years, she received many awards, including the Metin Göktepe Journalism Award, one of the most prestigious in Turkey. When clashes began, she reported from the towns Cizre and Nusaybin who were placed under curfew. She was detained in July 2016 in Mardin, one day after she left Nusaybin, and was placed in pre-trial detention for 5 months then released under judicial control at her first court hearing in December 2016. At the end of the trial in March 2017 Zehra Doğan was sentenced to 2 years 9 months and 22 days for propaganda because of her news coverage and a painting she depicted. She was subsequently released on February 24, 2019. Zehra Doğan has received many awards for her work and courage and participated in a number of exhibitions such as Art Basel, “OVR: Miami Beach”, December 2020; Art in Protest by Human Rights Foundation (HRF); Prometeo Gallery, Milan. Italy, exhibition entitled “Beyond”, with a performance; Berlin Biennale, Germany and the Graphic book made in prison, “Xêzên Dizî” (Hidden Drawings); all were in September 2020; The Santa Guilia Museum, Brescia, “Avremo anche giorni migliori – Opere dalle carceri turche” from November to January 2019; and Tate Modern, London, installation entitled “Ê Li Dû Man – What’s left of it, in May 2019.

.jpg)

Elettra Stamboulis is a curator and comic writer based in Ravenna, Italy. As a curator, she presented Marjane Satrapi's, Joe Sacco's, Zograf's personal exhibitions and many others international drawers in Italy; she is the founder and curator of Komikazen International Festival of Reality Comics, taking place in Ravenna since 2005.

She wrote the script of the Graphic Novels: The Tamer of Istanbul (Comma 22, 2008 – ebook in english by VandaPublishing), Officina del macello (Edizioni del Vento, 2008 – Reprinted by Eris Edizioni 2014), A cena con Gramsci (Becco giallo 2012), Arrivederci Berlinguer (Becco giallo 2013), Pertini tra le nuvole (Becco Giallo 2014), Diario segreto di Pasolini (Becco Giallo 2015), all drawn by Gianluca Costantini; Small Jerusalem, drawn by Angelo Mennillo in Greek (Jemmapress 2015). She has also written many short stories translated in English, French, Turkish, Greek, in particular for Le Monde Diplomatique, Babel, Leman.

Pictures

Art Images Copyright Zehra Doğan https://zehradogan.net

Pictures of Elettra Stamboulis and Zehra Doğan Courtesy and Copyright of Elettra Stamboulis https://www.stamboulis.org

Video of Art Performance by Zehra Doğan at the Santa Giulia Museum, Courtesy of Elettra Stamboulis

Zehra Doğan by Gianluca Costantini, Copyright Gianluca Costantini https://www.gianlucacostantini.com/ , Courtesy of Elettra Stamboulis

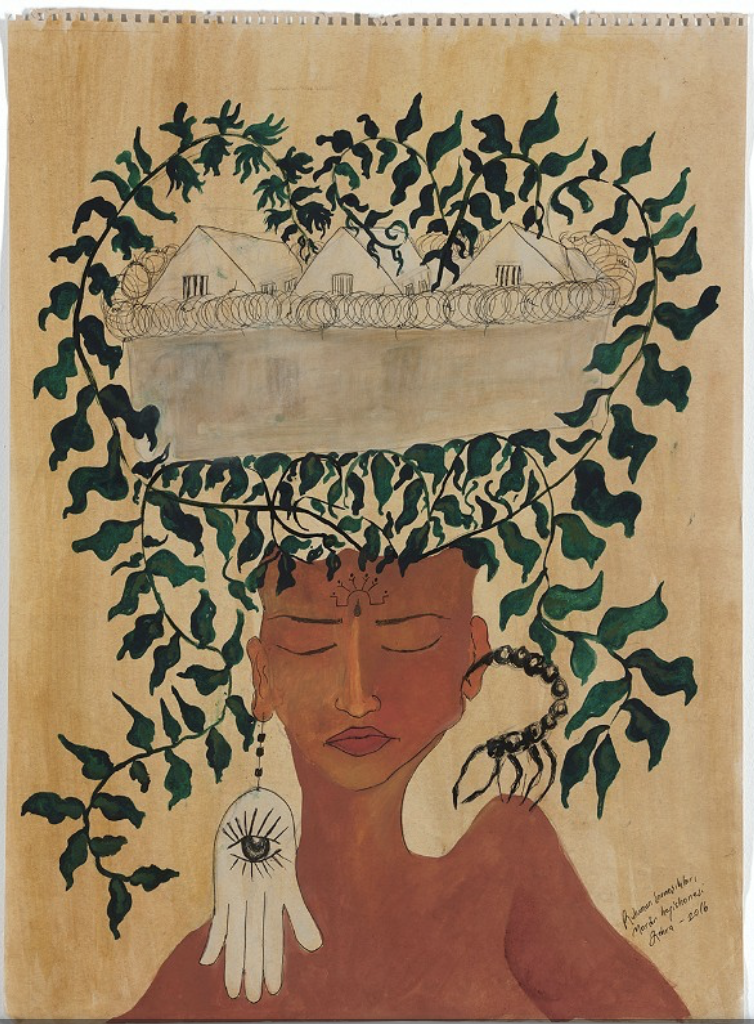

"RUHUMUN SARMAŞIKLARI" (Iives of my soul) by Zehra Doğan

62 x 45 cm. On kraft paper, water paint. 2016, Mardin prison.

Collection Editions des Femmes